The Future of Big Box

I’m ambivalent about big box stores. I occasionally shop at places like Walmart, Costco, and Target, just like most people. I buy various packaged goods in bulk from these mega retailers to take advantage of a volume discount. I don’t moralize over these things. But when it comes to meat, dairy, and fresh produce I walk around the corner or down the street to my local mom and pop stores, farmers market, or Community Supported Agriculture plan. I’m fine with buying a pallet of inexpensive toilet paper that was manufactured on an industrial scale. Chicken? Not so much.

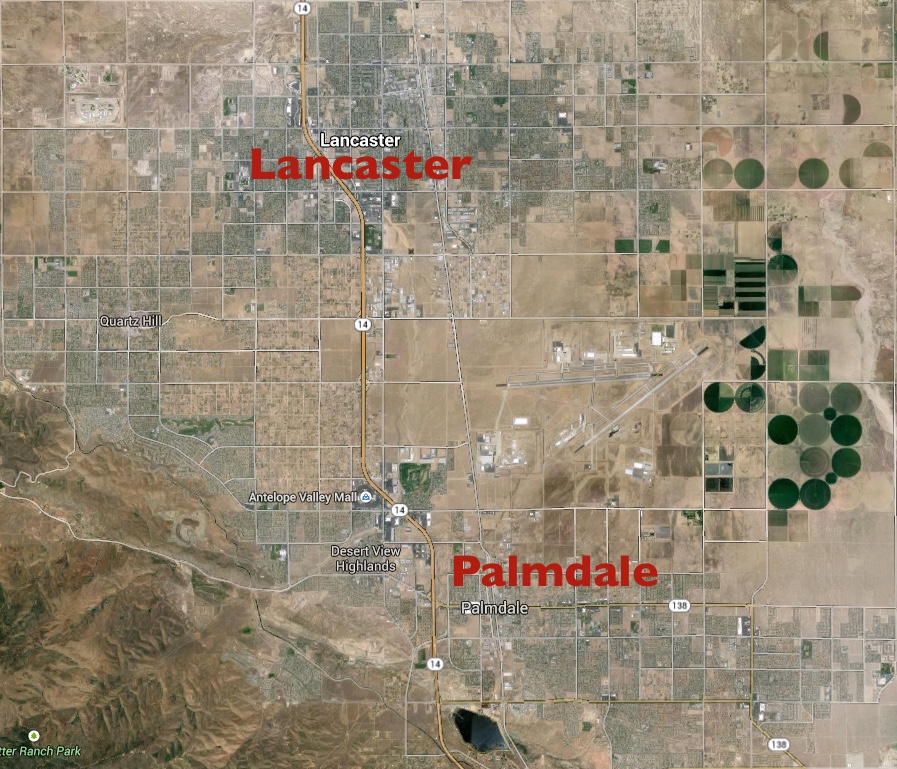

But I’m really interested in the giant retail buildings themselves. A large proportion of the North American landscape is dominated by big box stores and the associated land use pattern that we’ve all come to recognize. They’re so ubiquitous that we tend not to question how they came into being. I'm going to take some time to explore a retail development in the Antelope Valley in California. I use this example because it’s typical rather than unique. Whether you live in Florida, Texas, or Nebraska, the same dynamics are at work.

THE LANCASTER-PALMDALE RIVALRY

The story begins with a rivalry between the two contiguous municipalities of Lancaster and Palmdale. If you were to drive through the Antelope Valley you would have no way of knowing when you had passed through one town and into the other. Not only are they composed of identical building types, but their borders are incredibly intertwined and gerrymandered after decades of annexation in an arms race to see who could grow the fastest.

The big prize is always sales tax revenue from high volume retailers: car dealerships, big box stores, department stores, chain restaurants… Anything with a cash register will do. Like most towns the property tax revenue from residential development isn’t nearly enough to cover the costs of city services such as schools, road maintenance, and police and fire protection. Sales tax receipts are desperately needed to fill the gap. The construction and service jobs associated with new retail are also welcomed by city authorities. New growth is paramount at the economic development agencies.

With this in mind the City of Lancaster prepared a site for a regional shopping mall in the late 1980’s. The land next to the freeway was set aside, it was properly zoned, expensive infrastructure was installed, a “business friendly” package of heavy subsidies and sweeteners was put in place, and an extensive lobbying campaign was launched. Basically, Lancaster hiked up its skirt, put on a Wonder Bra and a lot of rouge and hoped a big strong regional shopping mall would come calling.

Unfortunately for Lancaster, it was Palmdale that successfully wooed the mall developer with a $20,000,000 incentive package back in 1990. The customer traffic heading to and from the new mall spawned a dozen adjacent retail sites that sprouted big box stores and a penumbra of chain restaurants and strip malls. It was a city planner’s dream for almost eighteen years.

What Happened in Lancaster

But then Palmdale was hammered by the economic crash of 2008. The mall lost its Gottschalk’s and Mervyn’s anchor stores. Palmdale’s economic development team felt it had no choice but to entice Macy’s and others to fill the void with multi-million dollar tax deferments and business “incentives." Remember, a big mall with no anchor stores rapidly fails as foot traffic declines. In fact, no developer can even secure bank financing to build or improve a retail complex unless they already have signed contracts with a couple of big stores. That’s why the largest stores in any mall pay the lowest proportional rent. The real cost of the mall is carried by the smaller shops and, very often, the tax payers.

A Cinnabon pays a great deal more per square foot in rent than a big anchor like Macy’s. The Cinnabon is also far more productive and pays more tax and employs more people pound for pound. The anchors effectively take up a lot of space, negotiate with veiled threats, pay as little rent as possible, and virtually no tax. That’s standard business practice across the country.

The idea that a town can repeatedly offer tax abatements to the same property in the short term in order to create tax revenue and prosperity over the long haul is a bad economic model. In fact, having neighboring towns race to see who can repeatedly impoverish themselves the most in an attempt to grow rich on new business is also a bad plan. Both towns know private corporations actively game the system, yet they can’t seem to help themselves. They still wet their pants at the thought that the next town over might get the new Applebee’s or Jiffy Lube instead of them. It’s a form of institutional insanity.

What Happened in Palmdale

Since Lancaster couldn’t have the regional mall, it needed to find a new use for the land it had set aside. There aren’t many things that can fill that kind of space. Like the mall in Palmdale, it needed to be something that would serve as a catalyst for growth all around it. And it had to be something that Palmdale didn’t already have. So Lancaster built what was intended to be a regional entertainment center with a baseball stadium, hotel, multiplex movie theater, and a premium outlet mall. "Build it and they will come."

In 1995 the city of Lancaster spent $14,500,000 to build the baseball stadium in the hope that economic growth and development would spring up all around it. So a decade on what does the area look like?

Near the ball park is the Lancaster Marketplace – an outlet mall. I checked the official management website and the leasing agent lists half the stores as “available”. The spaces that are occupied include a dialysis clinic, a dentist, various nail salons, a recycling center, an evangelical church, and a few outlet stores that sell sneakers and jeans. This clearly isn’t the economic engine or tax base that the city had originally envisioned. It wasn’t simply the economic crash of 2008 that brought this place down. It was the institutional over-supply of retail space across the entire region. No town needs the insane number of shops that were induced into being by overly-optimistic developers and tax-starved municipal authorities.

Here’s the movie theater with all the modern bells and whistles: 22 screens, IMAX, 3D, stadium seating, all digital, a sound system that can pull the gold fillings out of your teeth… you name it. It’s a massive stand alone building with an even bigger parking lot. In fact, the collection of reserved handicapped parking spots close to the front door is as large as many ordinary parking lots at lesser movie theaters. But here’s the problem.

This is the old 12 screen movie theater half a mile away. It’s now a “second run” theater catering to the discount matinee crowd because it can’t possibly compete on anything other than price with the new super deluxe theater down the road.

And here’s the old, old movie theater that used to play second run shows when the 12 screen opened up. It was eventually driven out of business. The building sat empty for a long while until someone attempted to operate a hairdressing school at the location. That business failed and now the place sits empty again. The new growth isn’t adding to the town’s economy. New bigger buildings simply replace old buildings that never get repurposed.

Across the street from the struggling outlet mall and old 12 screen movie theater is a Walmart. In fact, there are two Walmarts right next to each other. The older “small” Walmart was built in 1990. In 2006 Walmart decided it was time for a new larger super store and there was still plenty of land available in the same retail complex. Even as I stood on the far edge of the enormous parking lot with a special wide angle camera lens, I still couldn’t get the two side-by-side buildings into view in a single frame. These buildings are massive.

Here’s what the old Walmart looks like today – just twenty five years after it was built. In theory, a new big box retailer would have opened up in the old Walmart building, but instead it has remained empty since 2006. There’s simply no market demand for these hulking ruins.

What's NExt

One of the popular urban planning strategies in vogue these days is to reuse dead retail buildings by converting them to “meds and eds.” Junior colleges and medical centers are of a suitable size that they can fill old big box stores and help reactivate the surrounding space. The above photos are of the newest medical center in Lancaster. It’s solar powered and hyper energy efficient. The native draught tolerant landscaping is irrigated with recycled gray water. High quality regionally appropriate public art is in abundance. And it’s almost exactly the same size as the old Walmart that’s been sitting empty for the last decade. But where is it?

If you were to search out the least developed patch of this already sprawling hopscotch part of Lancaster… that’s where. Why? I’m sure there were all sorts of reasons having to do with the medical people, the developers, the city planners, the banks… Maybe the medical center is expected to be the engine of economic development in this patch of the desert and they want loads of extra room so they can spread out in the future. Or maybe that’s where the really cheap land was near a freeway cloverleaf. Or perhaps the medical center was too prestigious to be located in a low rent shopping plaza. Who knows?

There was still a big chunk of the old mall site that couldn’t be filled with much of anything. Reluctantly the city rezoned it for single family residential subdivisions. Housing wouldn’t bring in tax revenue the way retail development would, but it was better than nothing. Growth was growth and Lancaster needed it badly. From Google Earth view you can see the cul-de-sacs carved into the desert. So far… no takers.

Here are more photos of that old regional shopping mall site and the surrounding area. Notice the roads that were built to accommodate all the anticipated growth. But they built and no one came.

This story isn’t unique to the Antelope Valley. These same patterns of development play out all over the country. Some of you may dismiss this particular part of the world and assume your town is much better at managing its affairs. You may have more employers pumping money into your local economy. Or perhaps you live in a more sensible state with a pro-business legislature, unlike the folks who run California. The truth is that California just did everything earlier and faster, and on a grander scale than other places. Your turn is coming.

(All photos by Johnny Sanphillippo)