It’s Not Just Parking Minimums That Can Shrink

Addressing the failings of parking policy is a mainstay topic of the movement for financially resilient cities. But so far these discussions have centered on reducing or eliminating parking minimums. But let’s back up for a moment and talk about the minimum size of those spaces (also called stalls) and how those seemingly innocuous strips of paint may contribute to economically fragile, less livable cities.

Lodi, California is a city of over 65,000 people just north of Stockton in the California Central Valley. As a result of its location, groundwater and heat are two *ahem* hot topics in planning here. Shade trees and green infrastructure in parking lots in general are important practices to incorporate — not only because of the many benefits of urban trees, but because these practices help reduce the pressure on expensive municipal stormwater management systems and help recharge the depleted water table in this semiarid region where agriculture drives the local economy.

Lodi encourages best practices for parking lot design in its Development Code guidelines. The guidelines recommend planting enough shade trees in the parking lot to shade fifty percent of the asphalt area within five years from the time of their installation. The guidelines also recommend visually breaking up large paved areas with landscaping and reducing the amount of stormwater run-off resulting from the lot.

But the Development Code’s mandatory parking design standards, just four subsections earlier in the ordinance, require continuous curbing between all parking and landscaping areas. The design standards also do not contain any requirement or incentive for stormwater reduction, nor any requirement or incentive for actually planting shade trees.

The result of these discrepancies? Cities get what they require and potentially lose what they desire when design requirements do not provide a carrot or a stick to accompany best practices.

Parking lot and storm water designs persist long after big box stores close. Source: Doug Bojack

A well-shaded parking lot in Sacramento. Source: Georgia Silvera Seamans @ LocalEcologist.org

So how does the city move from acres of barren, unshaded asphalt, to leafy lots that provide stormwater benefits? Certainly, requiring less parking would allow developers to invest their parking lot budgets more deeply in the resulting fewer spaces, perhaps resulting in better adherence to the desired guidelines. But there’s another culprit to consider — the actual dimensions of the spaces the developers must provide.

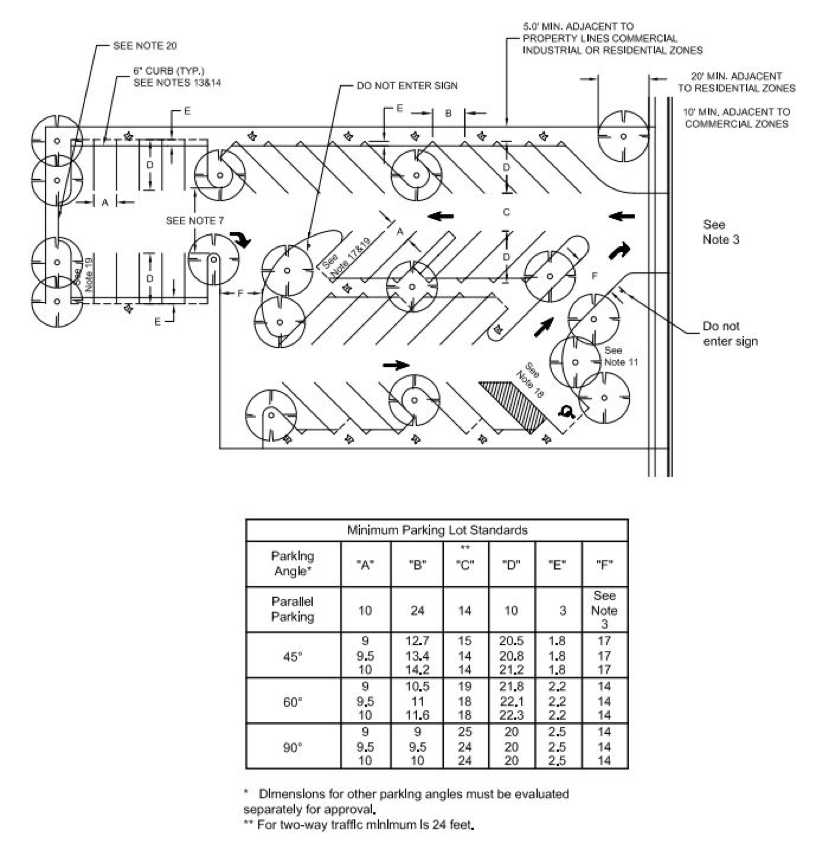

Lodi, like many jurisdictions around the country, mandates parking space size minimums as well as the number of parking spaces. For illustrative purposes, I will compare Lodi’s requirements with Sacramento’s, California’s capital 35 miles to the north.

First, Lodi:

Parking design standards in Lodi. The parking space size minimums are found in the bottom table and are arranged by degree of parking angle. Source: Lodi Municipal Code.

And now Sacramento’s:

Sacramento’s parking space minimums, also arranged by parking degree angle. Source: Sacramento City Code.

By examining just the 90-degree parking stall type, the most commonly seen in large commercial parking lots, it is evident that one parking lot stall in Sacramento contains 153 square feet. A similar stall in Lodi may be 200 square feet — over 30 percent larger. These few dozen square feet per space have an outsized impact on the design and feel of large parking lots.

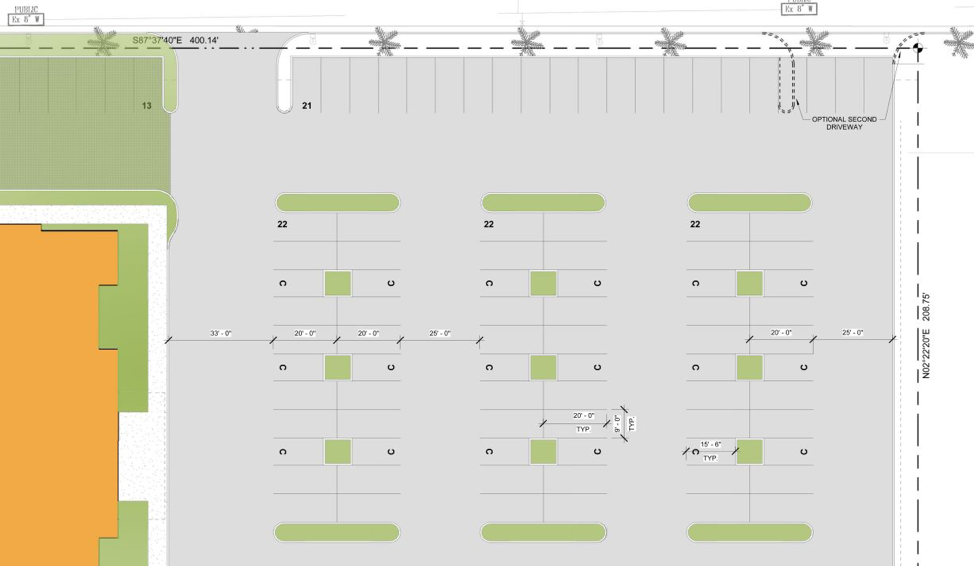

Let’s consider a recently approved infill development in Lodi that contains 120 parking stalls (a reduction from the required minimum of 130 spaces, which in itself is a topic for another article). The extra-large parking stall size minimums result in more than 5,600 square feet of extra, impervious asphalt required for the parking lot instead of permitting the developer to install beneficial landscaping or extend the actual property-tax-generating building envelope.

Just some of the large 120 parking stalls required for an infill development. Source: City of Lodi

Moreover, the oversized spaces mean that, even when shade trees are added to the parking lot, they are confined to individual tree wells. Individual tree wells can only support small shade tree species that provide minimal shade, and which will likely have yet smaller, stunted canopies due to being planted in what effectively amount to concrete coffins surrounded by compacted soil. Individual tree wells are also likely too small to act as bioswales, thus preventing rainfall from recharging the water table.

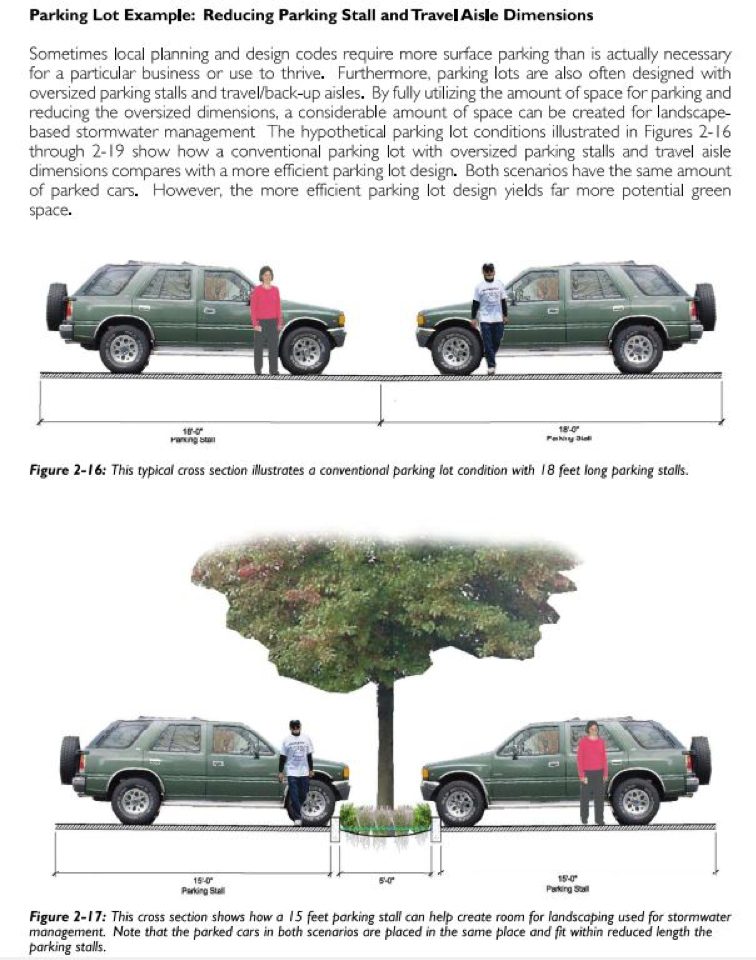

However, by reducing parking space size requirements, the city could increase canopy coverage, provide stormwater benefits, and permit builders more flexibility in adding economically productive developments before even touching parking minimums. The hypothetical parking lot conditions illustrated in the figures below show how oversized parking stalls can be reduced to add additional shade trees and safer pedestrian access through the parking lot while still keeping the same number of parked cars. Note that Figure 2-16 assumes that the starting parking stall is 18 feet long, while Lodi’s are already two feet longer.

Cities can make it easier to add green infrastructure by reducing parking space sizes. Source: San Mateo County Sustainable Green Streets and Parking Lots Guidebook

Reducing the amount of asphalt poured for parking stall sizes has the additional benefit of leaving critical soil space available to support shade trees. Recommendations for the number of cubic feet of soil to support shade trees vary, but easing developers’ ability to leave uncompacted soil on the site is a way to provide necessary rootable area for these trees by opening up individual tree wells to greater landscaped area.

Once a city recognizes that even its parking space stall dimensions matter to providing the public goods of shade and stormwater management, a logical concurrent step to take is including incentive- and mandate-based incentives to beneficially use the freed-up landscaping through revisions to the city’s parking ordinance. As one county guidebook notes:

Reward-based incentives compensate a developer or property owner for incorporating green street and parking lot elements into their project. This type of incentive may include utility fee discounts, tax benefits, project grant funding, or even expedited review of development proposals. Reward-based incentives are particularly applicable to private development associated with parking lot projects. However, when private development occurs in conjunction with public streets, reward-based incentives can also apply. An example of a reward-based incentive is the City of Portland’s Clean River Rewards Discount Program that allows up to a 35% reduction in residential or commercial stormwater utility fees for employing certain landscape-based stormwater management strategies on-site.

Conversely, mandate-based incentives require developers to implement green infrastructure strategies for parking lot designs, or discourage the departure from these strategies by increasing levied stormwater management fees.

In summary, for reluctant jurisdictions, starting a conversation about your city’s parking space size minimums may be a more politically palatable entry into addressing the negative externalities of surface parking lots than diving into parking space minimums. Beginning with an incremental step can open the door to having a community consider what local ordinances can do to create and protect prosperous places.

About the Author

Doug Bojack is an attorney with a background in brownfields, economic development, and grantmaking. Doug is a Class of 2017 graduate of Leadership Lodi and chairs the city's community development advisory body. He writes this piece in his personal capacity.

When the owners of Lawrence Hall bought the abandoned building, they had a vision of reviving it into a food hall that would support small businesses and help their community thrive. They never imagined that a few parking spots would put their dream on hold for seven years.