My trip to the White House

The view of the West Wing from our meeting room.

Last week I received an invitation to attend something called The White House Convening on Rural Placemaking. If that wasn't cool enough, I scrolled down the invitation and noted the location: The White House. This was supposed to be my first week since the end of August without a trip but one just can't say no to that.

As an interesting side note: While I'm not going to suggest that my wife and daughters aren't proud of me, they tend to concern themselves more with what I'm not able to do when I'm away from home as opposed to the great things I'm doing when I'm on the road. I think that's natural and I don't expect a continuous stream of admiration from them. Still, they all treated me like some kind of celebrity this past week. My youngest even shared my upcoming trip with her classmates. All of a sudden, Dad is kinda cool. I'll take it.

The meeting was on the White House grounds but was actually in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, a large and impressive complex just west of, and connected to, the West Wing of the White House. We met in the Indian Treaty Room. The name conjured up images in my mind of Ojibwe and Lakota chiefs in their finest battle dress affixing their mark to paper. According to Wikipedia, this seemingly was the extra room where they stashed the treaties (possibly to avoid reading them after they were signed).

Eisenhower did the first televised press conference in this room and there is a cool picture on Wikipedia of President Obama doing something similar. The Bretton Woods agreement -- which essentially ended Britian's empire and created the post-World War II monetary system dominated by the American dollar -- was signed in the Indian Treaty Room. For a guy from a small town in Minnesota who started writing a blog a few years ago, this was all pretty surreal.

Waiting in line with Mickey Howley, the best Main Street local program manager in the country.

We were asked to arrive at 8:30 AM for a meeting that would start an hour later. We would need to go through security, of course, before we entered the grounds. I arrived even earlier and was a little concerned I might be in the wrong place until I ran into a familiar face. Mickey Howley, the Main Street Manager of Water Valley, Mississippi, actually wound up being one of the presenters. Right on; he's the best Main Street manager I've ever met (and I've met a lot).

Besides the White House and related cabinet agencies, the main organizations putting together the meeting were Project for Public Spaces (PPS) and the National Main Street. I'm familiar with both and have respect for the work each is doing. Fred Kent of PPS has been promoting this kind of approach for a long time. In fact, way back when it was a crazy idea, which makes him quite a visionary.

For those of you not familiar with the term "placemaking" I'll offer my own definition. Placemaking is a focus on building a place for people to be in instead of a place for people to drive their cars through. The term did not exist a century ago because it would simply have been called "urban design". Today, after two generations of disassembling our cities to accommodate increased auto mobility on the misguided theory that doing so was the key to our prosperity, we actually need the art of placemaking to reconstruct what actually works.

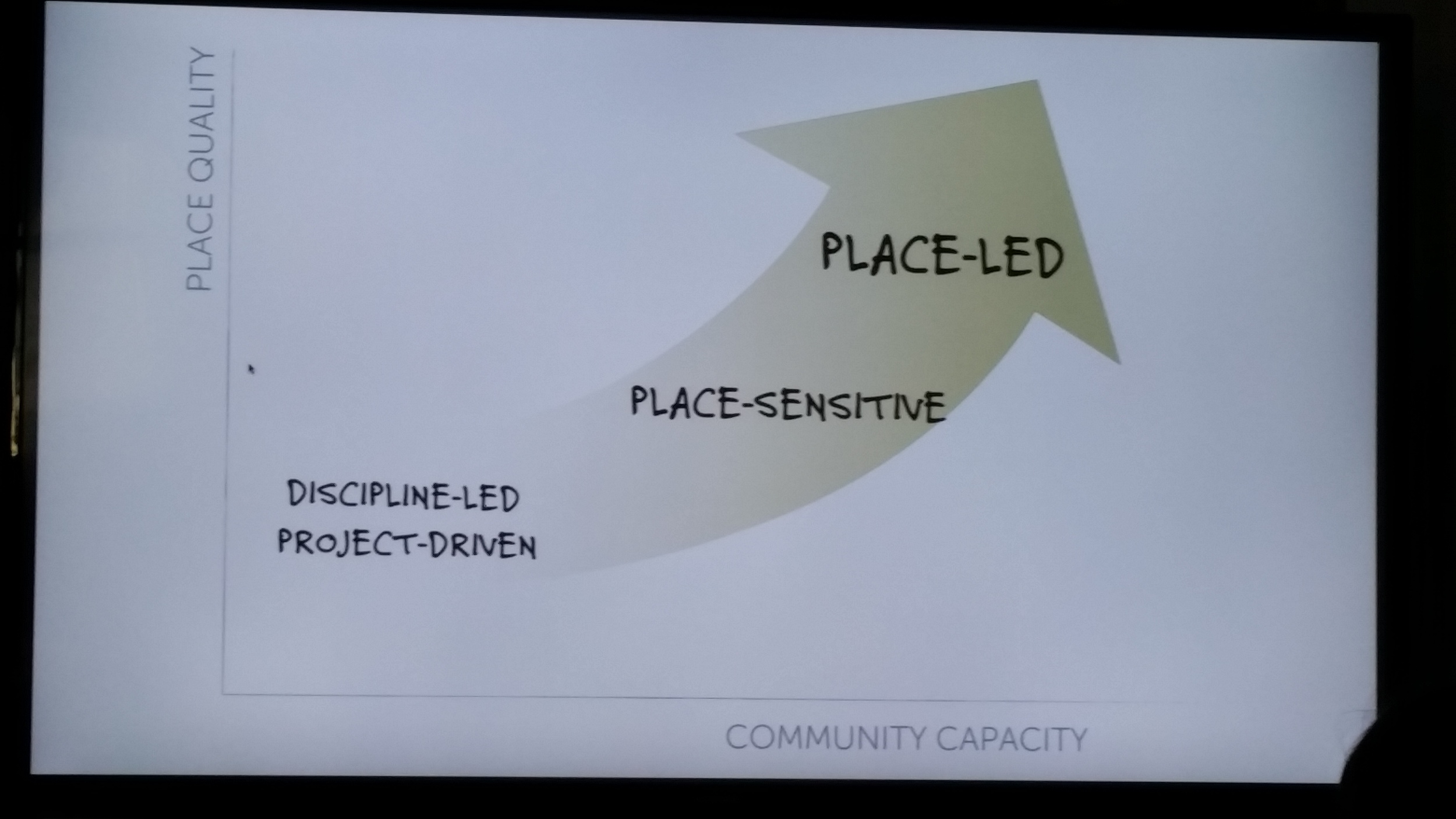

One of Fred Kent's slides suggesting that we get better places when we take our cues from the community. Chaotic but smart.

That those in the highest reaches of our federal government are aware of the many implications of this shift is a positive sign.

Throughout the day we heard from a number of officials -- both from the executive branch as well as practitioners -- who talked about their efforts at placemaking. From a Strong Towns perspective, there was one thing that was specifically encouraging: Multiple times throughout the day, high level officials acknowledged how federal efforts of the past have created many of the problems we were now needing to solve. There seemed to be an understanding -- not necessarily among all the attendees but pervasive among the federal officials -- that the top-down approach (what we call "orderly but dumb") was not going to solve these problems.

So the question then becomes: What can a bunch of people in Washington DC do with their tools -- large budgets and coarse regulation -- to bring about chaotic but smart, fine-grained and nuanced change at the local level? I'm not sure I know the answer, but as I look at people like Fred Kent with Project for Public Spaces or the National Main Street Center, I see a better conduit for transmitting success than government bureaucracies. That's not an approach without downside -- imagine the controversy and partisan passion surrounding a group like Planned Parenthood now being applied to the Main Street program -- but it might be the best approach available to us today.

If you gave the public officials in my city a $1 million grant for improving the quality of life for people in the city, there is no doubt in my mind that they would totally screw it up. We'd do something colossally stupid because that dollar amount is right in the stupid sweet spot for a city of 13,500. However, if organizations within the city, as well as the city itself, over the next few years received 50 grants of $20,000 each -- the same amount of money -- for the same purpose, I think we'd screw up some, but there would also be some great successes that would break through that we could build upon.

This would require our federal officials to give up some control and it would require our citizens to give up some accountability. Said differently: It would require a broad acknowledgement that small scale failure is one essential component of successful innovation. Can citizens allow the government that wiggle room? Can government officials then be brave enough to fill it? Can we all be humble enough to acknowledge that there are no simple solutions? These are open questions, but I'm glad the Strong Towns movement is part of the national conversation seeking to answer them.

Charles Marohn—known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues—is the founder and president of Strong Towns. He is a land use planner and civil engineer with decades of experience. He holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and a Master of Urban and Regional Planning, both from the University of Minnesota.

Marohn is the author of Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity (Wiley, 2019) and Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town (Wiley 2021). He hosts the Strong Towns Podcast and is a primary writer for Strong Towns’ web content. He has presented Strong Towns concepts in hundreds of cities and towns across North America.