The Fatal Flaw in Your Town's Development Pattern

A small town in Texas is doing exemplary work to put Strong Towns principles into action. Several Strong Towns members lead the local government in Fate, TX and they've used Strong Towns concepts in a number of ways to help themselves and their community to better understand the financial impact of their development pattern. We often encourage towns to #DotheMath and Fate has answered that call.

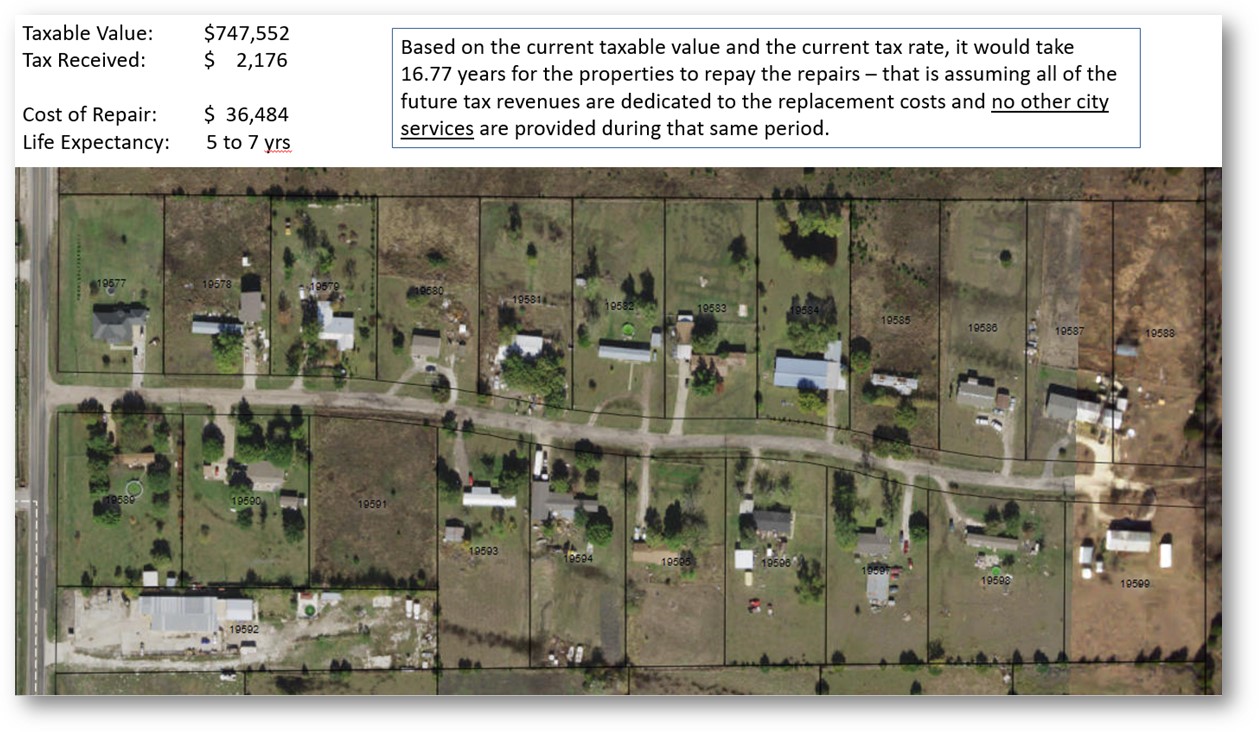

Justin Weiss, Assistant City Manager of Fate shared with us a slide from a presentation at a recent city council meeting, which perfectly illustrates the financial problem with the suburban development model. When a dead-end street in Fate needed repairs, Justin and his colleagues used basic math to look at how much those repairs would cost and how many years' worth of taxes the residents along this street would have to contribute in order to fully fund the repairs. The results were deeply troubling and yet they're the norm in towns and cities across the country.

Courtesy of the City of Fate

Justin explains:

The goal is to demonstrate how those served (almost exclusively) by adjacent infrastructure have no way to pay for it when it comes time to replace/repair.

In this scenario, the neighborhood of about 22 properties pictured above was recently annexed by the City. In doing so, the City also took on their [dead-end] road, which was the County’s responsibility previously. It appears it was neglected for many years as it was ranked one of the worst in the road assessment performed by staff and engineer earlier this year. During the budget process last summer, Council directed Staff to create a roads plan (with no dedicated revenue source)... The “solution” for this particular road varied from grinding it up and leaving it as a dirt road to a full reconstruct with asphalt or concrete.

Staff suggested the cheapest fix (next to grinding up the whole thing and leaving it as a dirt road) which was to do a chip seal at a cost of about $40,000. It really isn’t a fix, mostly cosmetic (only lasts a few years) and doesn’t address base failure, etc. We couldn’t in good conscience recommend building a brand new road…

Even with the cheapest method selected, as you can see in the slide above, what stands out the most is the fact that the residents of that neighborhood would be paying for nearly 17 years for a fix that would last them MAYBE 5 to 7 years, and that’s if NO OTHER city services are provided during that same period. In other words, if we took all the property tax derived from those properties, and solely allocated them for the repayment of the repair of their road, it would take them 17 years to pay for it based on the current tax rate.

Why measure the project based only on the tax revenue of the homes adjacent to the street? Because it's a dead-end cul de sac. These residents are literally the only people using the road. And they can't hope to pay for it.

If it seems like insanity to propose a simple paving project that would require tax revenue for 2 to 3 times longer than the road would actually be in use for, realize that this model is in play in towns and cities nationwide — yours included. (Look up the tax values in your town and see for yourself.)

It's like getting a 15-year loan on a car that's so crappy it will probably only last 5 years. Or buying a phone with a 3-year payment plan when you know full well that you'll break or lose that phone within a year. Actually, it's like taking every penny you have each month and only spending it on that car loan or that phone payment, because remember, the numbers above are based on the assumption that all tax revenue from the homes on this street is going solely to pay for the road and not to pay for the many other things your tax revenue needs to cover (schools, police, fire, etc.)

So why is this the case? Why does an average-looking street in an average-looking town suddenly appear completely bankrupt?

Simple: we built it that way. Instead of using the traditional model of development in play for centuries — the one that built slowly over time, without a lot of outside money, bit by bit, story by story — we've adopted the suburban model of development across the country. In this model, homes and businesses are built all at once. Whole streets are constructed in a manner of months with big influxes of cash or loans, and the buildings are spread out, requiring a car to get from place to place.

When our towns changed course in the 1950s and 60s from the traditional to the suburban model of development, they were setting themselves up for this financial mess — only they didn't do the math on maintenance costs that would've showed them that. They just kept building roads and subdivisions and strip malls. Today, we're left to figure out how to pay for it all, and because so many homes and streets were built at the same time, they're all falling apart and in need of maintenance at the same time, too.

While a traditional street built a hundred years ago may have housed 40 or 50 families and businesses in compact, modest buildings, the typical suburban street as exemplified in Fate now houses just over 20 families in homes with large yards, spread apart from one another. We have half the number of households paying for a street that's twice as big. No wonder the math doesn't work out.

For Fate, doing this sort of math, though, has made an impact. The city council decided not to approve the $40,000 repair on the road and instead directed staff to identify cost savings through alternatives to paving. Recognizing the lopsidedness of tax revenues compared with current and future liabilities, the Mayor and Councilmembers in Fate are leading the charge to improve the fiscal resiliency of the community. As one example, the Council recently approved a revitalization project targeting failing infrastructure in the downtown area to promote more fiscally productive vertical mixed-use developments.

All of our communities need to start paying attention to the math behind our development pattern and taking a hard look at how to make our cities more financially solvent. That's how you build strong towns.

Wanna dive deep on this topic? Check out our Growth Ponzi Scheme series.

Thank you to the leaders in Fate for sharing their knowledge and graphics with us.