The Ignorant and the Elites

I live in a small town in Central Minnesota. We have lots of diversity here; we have people of Swedish descent, Norwegian descent and Finnish descent. We even have some Germans. What we don't have in large numbers are Americans of African descent.

Even so, growing up, that did not keep me from pretending that I understood African Americans. That I could diagnose -- and properly prescribe solutions for -- the challenges being faced by the black community. After all, we're all Americans. There's nothing that a little bit of hard work and good moral standing can't fix. At least that's what my grandparents told me.

Of course, the world is far more complicated for me now than what it once seemed. I'm not going to suggest that I'm in any way enlightened, that I know or understand substantively any more about the experience of African Americans than I once did. I will claim, however, one major difference in my life. Today I listen.

I listen and, even when it doesn't make sense to me, I try to understand. First and foremost, however, I work to deeply listen.

“The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time.”

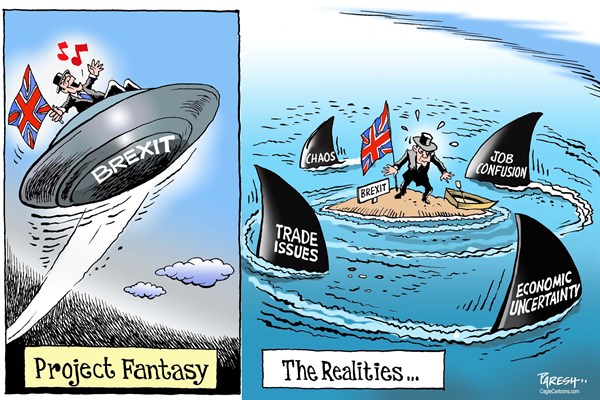

The day after the United Kingdom referendum on membership in the European Union -- the Brexit -- that famous quote kept circulating through my mind. Not because Brexit was going to lead to the deaths of tens of millions in two global conflicts, dislocate tens of millions more and ultimately usher in such horrors as the Holocaust and atomic weapons. No, the quote kept going through my mind because of the disproportionate level of drama being manufactured over Brexit, a reaction that suggested cataclysmic consequences.

And, of course, made for a good proxy for many to frame America's upcoming political decisions.

Light versus dark. Good versus evil. Open-minded versus closed-minded. Enlightened versus ignorant. Hate versus love.

What is sadly ironic is that advocates for both sides in the Brexit conversation, as well as those vested in our current political theater, see themselves as the force for good and the other side as a force of literal evil. Nobody is listening.

Now, mine is not a lament of the Rodney King variety -- can't we all just get along -- because, as most of you know, that's not who I am. I don't associate with any political parties today, not because I don't have very strong opinions about what is right and what is wrong, but because I believe the conversations and debates taking place in the political realm are largely irrelevant. They are staged theater. They do not substantively address things that truly matter to people. They are not crucibles for discerning policy. They do not set the stage for consensus building or effective governance.

More important than not associating with a party, I'm also not going to be a pawn in their game. I'm not going to spout their lines. I'm not going to share their propaganda. In short, I'm not going to take complex issues, embrace a simplistic framing of that issue and then vilify those who do not agree. And I'm not going to allow those around me to do so either. If you're going to hang with me over the next five months, you're going to have to respectfully listen.

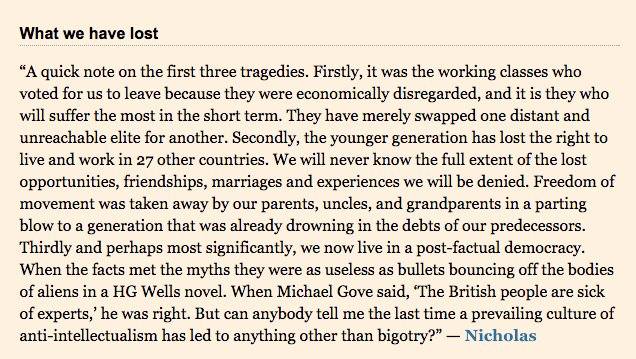

Since our audience tends to lean professional, well-educated and widely traveled -- as well as young -- I'm going to assume broad sympathy for the "Remain" camp among those reading this now. That's not a stretch; I try to associate on Facebook with as many of you as I can and my feed was displaying near hysterics after the vote. One of the more sober responses was this post, an excerpt of a comment that a great number of my friends shared.

First, the working class. Those fools have only hurt themselves -- they know not what they do -- and will not find the relief they claim to want (as they are merely swapping one elite for another). The corollary in this country is mocking so-called anti-government types for wanting to "keep government out of my Medicare." On the face, it's absurd. I agree.

Here's what's not absurd: Politicians have wanted to make college more affordable yet, after decades of government intervention, tuition (not to mention public spending on education) rises far higher than the rate of inflation. Politicians have wanted to make housing more affordable yet, after decades of government intervention, home ownership rates among the poor are as low as ever and middle class families must have two working adults to afford a median home. Politicians have wanted to make medical coverage more affordable, yet the more government intervenes in the medical system, the more unaffordable it becomes for the average blue collar person.

It's not unreasonable for someone working two part-time jobs to make ends meet to believe this system isn't working for them. It's not a leap to see them looking at the people in the education system -- salary earners who encouraged that now blue collar wage earner to take out student loans that paid the educators' salaries but does little for the wage earner -- with suspicion and envy. Why do government workers have union protections, competitive salaries and good medical coverage while my taxes keep going up and my job seems less secure each day? Those observations might not be the entire story, but they're not wholly unreasonable.

And it's also not crazy -- in the long absence of progress following successive unfulfilled promises -- to support those who would, in a sense, shake the etch-a-sketch and reset the drawing. That it makes those who the system is seemingly set up to benefit -- the educated, the connected, the moneyed -- freak out is a confirmation of sorts. You may find the little people to be ignorant, but they are not stupid.

I'm going to quote the American political philosopher Michael Sandel in an interview with The New Statesman:

I have no sympathy for Trump’s politics but I do think that his success reflects the failure of established parties and the elites in both parties to speak to the sense of disempowerment that we see in much of the middle class. The major parties have failed to speak to these questions. What Trump really appeals to is the sense of much of the working class that not only has the economy left them behind, but the culture no longer respects work and labour.

This is connected to the enormous rewards that in recent decades have been lavished on Wall Street and those who work in the financial industry, the growing financialisation of the American economy, and the decline of manufacturing and of work in the traditional sense. There is also the sense that not only have jobs been lost through various trade agreements and technological developments, but the economic benefits associated with those agreements and those technologies have not gone to the middle class or to the working class but to those at the very top. That’s the sense of injustice; but more than that, the fact that the nature of political parties – I’m speaking about those in the US – have become, since the time of the Clinton years, heavily dependent on both sides, Democrats and Republicans, on the financial industry for campaign contributions.

I'll just add to that, while many young and educated people believe that the deficiencies of our current system can be corrected after-the-fact through proper tax rates and redistribution programs (and maybe some job training programs or free tuition), many blue collar workers are beyond skeptical of such schemes. The skepticism is not based on the theory behind the policy but on the fact that the policy doesn't originate from a place of true respect.

Second, freedom of movement. In short, the anti-immigrant meme. It's a powerful one because there is seemingly no limit to the number of deeply racist individuals seeking a camera or a microphone. I don't say that to downplay racism -- it's a complex reality and, as I acknowledged at the top, I'm on the privileged side of that conversation -- but 52% of UK voters wanted the Brexit. More than half.

Half of the voters in the United Kingdom are not racist, in the operative sense. They are not xenophobic. They just aren't. Not everyone in the U.S. who is supporting tougher immigration policies or border controls is operatively racist or xenophobic. There are some -- way too many -- but, when one half of the population reflexively lumps the other half of the population under such a polarizing label, we create a mutual set of self-fulfilling insights. This is not the way to bridge an intellectual gap, especially with such a complex issue.

The charge of racism is one of the most fraught in today's society. One thing I learned from Malcolm Gladwell's book Blink is that we're all wired to be at least a little racist in the sense that we -- including even a mixed-race Gladwell -- have System 1 reactions based solely on racial characteristics. It is the slower processing System 2 that overrides those tribal instincts and, hopefully, allows most of us to be decent to each other. I will admit, however, that the topic of race scares me to no end. There are so many questions I'd like to explore, so many things I'd like to know better, but am often afraid to ask because ignorance in this realm -- and I am clearly ignorant in this realm -- expressed incorrectly is rarely a learning opportunity. In the extreme, it can be career ending.

And I'm pretty thoughtful, educated and well-traveled. Take someone who is not. Now throw in globalization and free trade -- more theories of the elite -- and the feeling that it is hard not to connect your own stagnating situation with the fact that people in a distant land are willing to work at slave wages doing the job you or your parent used to do. Now have some of these distant immigrants move to your state, your city or your neighborhood. They all live together, not quite fully integrating into the American culture, because that's the natural state of first-generation immigrants to a new land. They work cheaply and the big corporations want more.

The fact that this situation is naturally tense -- throughout human history migration has always been tense -- is made exponentially worse by the fact that you can't really talk about it, at least not in public, unless you're willing to be shouted down and called racist. The massive set of complex problems that comprise your life are never discussed openly because part of it deals with race. It's easy for me to see why this taboo then becomes the obsession. The lightening rod.

And why, when a prominent figure stands up who is seemingly unafraid to trample over these taboo topics, there might be a sense that this person could speak for you.

English writer Tom Ewing recently wrote:

One of the things you hear a lot is that talking about racism has stopped us having a “proper conversation” about immigration. But the opposite is also true. Talking about immigration has stopped us having a “proper conversation” about racism — it’s blurred the lines, given racists an off-the-peg excuse whenever they’re called on it.

Portentous and meaningful stat: 66% people who left school at 16 voted for Leave. 71% of those with university degrees voted to Remain.

— David Axelrod (@davidaxelrod) June 24, 2016

We need to have a proper conversation about racism. Branding half the population racist is not a helpful starting point. Acknowledging that 100% of the population have some racist beliefs but that most of humanity is comprised of decent, compassionate individuals seems not only to be a better way to have a dialog but also a more discerning way to constructively marginalize truly radical beliefs (and the pied pipers who play off them).

Finally, there is the entire issue of a post-factual, anti-intellectual democracy. For all of those who believe that people supporting a Brexit are nothing but a bunch of uneducated, dumb, flat earth rubes, I want to expose you to a Conservative MEP named Daniel Hannan.

Hannan represents a part of the UK in the European parliament. This is a short, six minute video of a speech he gave in a debate on the Brexit. I'm not showing this to you to change your mind or influence your thoughts on the vote. The only thing I want you to consider is whether or not this argument sounds anti-intellectual. Does this sound post-factual?

It's important to know that Hannan was front and center among the Conservatives in urging a Leave vote. He was one of the more prominent voices. And for those of you searching for post-factual conversation, Hannan appeared on a Sunday talk show debate with Remain advocate MP Emma Reynolds and, towards the end of the debate, asked her what she felt was the strongest argument for voting Leave. Here's the exchange that followed (listen here):

Reynolds: I don't think there is a strong argument.

Hannan: Any at all?

Reynolds: I don't think there is a strong argument for voting Leave.

Hannan: This is one of the things that puzzles a lot of people who are trying to make up their minds.

Reynolds: But then you don't think there is any benefits of us staying in the EU.

Hannan: Actually, you know what, I can see arguments on your side. It's not my job to tell you what they are but I can see them. But what is extraordinary to me is that people who think of themselves, and make such an issue about being broad-minded and reasonable, really struggle to see that there is another point of view at all, just can't put themselves in the shoes of people for whom the EU is not benefiting, which is the vast majority of people in this country.

Reynolds: Well I think there is a lot of scare mongering on your side about if we stay in what might happen because, actually, if we stay in we'll pretty much have the status quo.

Hannan is saying, "We don't agree but I can see your side, can you see mine?" and Reynolds replies with, "Your side is scare mongering." I highlight this because it is an exchange that happens continuously. The other side has no valid argument, no starting point based on anything but evil.

There was a fantastic article that came out before the vote titled The European Union and the Misery of Bigness. I recommend reading it all, but here's an "anti-intellectual" argument that -- presumably -- will "end in bigotry":

Years ago, the great Austrian economist Leopold Kohr argued that overwhelming evidence from science, culture and biology all pointed to one unending truth: things improve with an unending process of division.

The breakdown ensured that nothing ever got too big for its own britches or too unmanageable or unaccountable. Small things simply worked best.

Kohr pegged part of the problem with bigness as "the law of diminishing sensitivity." The bigger a government or market or corporation got, the less sensitive it became to matters of the neighbourhood.

In the end bigness, just like any empire, concentrated power and delivered misery, corruption and waste.

And that's the problem today with the European Union, big corporations, large governments and a long parade of big trade pacts.

In the global labyrinth of bigness, the European Union has become another symbol of oversized ineptness along with a technological deafness that ignores locality, human temperament, culture, ecology, tradition, democracy and diversity.

I'm going to today end with this: I'm not going to argue with you in the comments section about whether the Brexit is a good thing or a bad thing. I'm not going to debate whether or not the people who voted Leave are ignorant or enlightened. I don't want to discuss the global ramifications of Brexit. None of these topics are important to building a Strong Town.

What is important, and it's the only reason I'm writing this piece, is that we're not listening to each other. Even worse, our words and actions are making it impossible for us to listen to each other. Not only does this hurt our communities, it is making us ripe for exploitation.

If you follow us here at Strong Towns, you know that things are going to get more difficult for America -- much more difficult -- before they get better. You can be left-of-center and be a Strong Towns advocate and you can be right-of-center and be a Strong Towns advocate. Your politics do not matter. What really matters is whether or not you listen.

We need a movement of people who can work with others. People who, in desperate times, facing a vast array of complex problems, can lead people to respond rationally. If you want to be one of those people -- and I hope you will -- join me in working on your listening skills.

Charles Marohn—known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues—is the founder and president of Strong Towns. He is a land use planner and civil engineer with decades of experience. He holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and a Master of Urban and Regional Planning, both from the University of Minnesota.

Marohn is the author of Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity (Wiley, 2019) and Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town (Wiley 2021). He hosts the Strong Towns Podcast and is a primary writer for Strong Towns’ web content. He has presented Strong Towns concepts in hundreds of cities and towns across North America.