Mobility's Diminishing Returns

We like to believe that the United States is the land of opportunity. We also believe, for good reason, that increasing mobility increases opportunity. But when does this correlation break down? When do we go too far, to the point where the cost of improving and maintaining mobility actually stifles opportunity?

All of us at Strong Towns would like to say thank you to Eli Damon for his support of this blog, our podcast and the Curbside Chat program. Eli is also a frequent and valued contributor to the comment section here as well as on our Facebook page. It is those contributions - the intellectual as well as the financial - that are giving us the capacity to expand the concept of Strong Towns. Thank you so much, Eli. We're really fortunate to have you in our camp.

For those of who demand a rigorous statistical analysis for each idea put forward, stop reading right now. I am not going to help you here and, while I appreciate your passion, I'm not going to be able to answer all of your emails either. This post challenges decades of facts, figures and statistics so, in a room full of empiricists, I would be shouted down vigorously. It should be noted, however, in the tradition of Albert Einstein amongst others, that it frequently is not the answer but the question that poses the deepest insight.

Today we ask the question: Have we overvalued mobility?

Our friend of past online debates, Randall O'Toole, is a champion of both the auto-based transportation system and mobility in general. His argument is essentially that there is a correlation between mobility and prosperity, that the more mobile a society is, the more at liberty people are to follow endeavors that enhance life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Greater mobility increases job opportunities, shopping selection, service competitiveness, school choices and even the gene pool people have a chance to select from when seeking a mate. There is no question that, in a broad sense, he is correct.

The first chapter in his book, Gridlock: Why we're stuck in traffic and what to do about it, is called "Land of Mobility" and it makes the case that increasing mobility increases prosperity. In it he says,

Economists estimate that construction of new highways contributed to nearly one-third of the rapid economic growth the United States enjoyed in the 1950's and a quarter of the growth in the 1960's. The growth wasn't generated by construction jobs; it came from the increased mobility offered by new roads. It may be no coincidence that our economic growth slowed as highway construction tapered off in the 1970's and 1980's.

(I'll note that the slowing of economic growth also correlates to the end of the first life cycle of the new roads. This is the time that the long-term cost of maintenance started to kick in. But that discussion is a digression for another post.)

Let's look at mobility in a theoretical model. Assume you have City A and City B that are located 10 miles apart. Each has 10,000 residents. The year is 1945 and so these cities are connected by a railroad and then a series of small, poorly-maintained "roads" (more like trails).

If you live in City A, you work in City A. In 1945, it is not likely that the frequency or the timing of the trains made commuting to City B possible. The poor condition of the trails likewise probably made trips between the two infrequent. Someone living in between these two towns -- likely a farmer, logger, hunter/trapper or a hermit -- would travel some type of slow, winding trail in order to get to town. This was also likely an infrequent trip.

This situation is pictured in my crude sketch titled "Theoretical Mobility Model: 1946".

When World War II ended and we started building highways, we changed the mobility equation significantly, alla O'Toole's analysis. The railroad, with infrequent service between City A and City B, was augmented by a highway. Now, any time of day, one could take a 15 minute drive between towns. The advances in prosperity had to be immense. Business owners now had access to double the number of customers as well as twice as many employees to choose from. On the other side of the ledger, hard-working and skillful individuals had access to double the numbers of potential employers, increasing competition and wages. This is an economic advance right out of the dreams of Adam Smith and David Ricardo.

I've updated my sketch to reflect the "Theoretical Mobility Model: 1960". Note how there is no real change in the living pattern, just in the mobility options.

We should just pause here and note that this situation is hyper-efficient and productive. We are able to exchange goods and services back and forth and each city itself maintains a very efficient/productive pattern. This seems to be the peak of American mobility, if not in distance at least in options. Someone living in either of these cities of 10,000 can walk anywhere in their own town, can likely drive anywhere in their own town (although slowly), can visit the countryside by foot or by car and can travel between towns either by car or, less frequently, by train. For those seeking equity combined with mobility and efficiency, this theoretical model is the closest to maximizing all three.

At the risk of angering some who are turned off by such suggestions, I'll also note that this is largerly the condition of European cities circa 2011. The American development pattern is uniquely American, by our choosing.

Something happens in the next incarnation that I am not going to be able to show clearly with my sketches (if there is an artist out there that would like to help me make this case more convincingly, get a hold of me) and that is that the cities hollow out. If you want to see this visually, check out last week's posts from Monday (Leveraging public investments) and Tuesday (A brief look back) to see some before and after depictions. Converting our cities from efficient and walkable to auto-centric cost untold amounts of wealth and, while it allowed (dare I say, required) us to drive more, it did little to change the prosperity/mobility equation outlined in the prior two sketches. The primary advancement was connecting the two communities. Facilitating the movement of people from a row house in town to a single-family house on the edge of town may have created short-term construction jobs, but it did not expand the market in any dramatic way. Ditto with changing the downtown restaurant to a drive through on the edge of town. These created localized, short-term construction-related spending, but did not significantly change the long-term mobility/prosperity equation.

What did change the equation was the loss of passenger rail service. I don't know exactly when this happened, but I was born in 1973 and have no recollection of rail service in my town, even though we have a huge rail yard and I have family that worked there. There are "old timers" who talk about riding the rails, but my educated guess was that this service had widely disappeared by 1980.

Again, I'll update the sketch to depict the 1980's theoretical model.

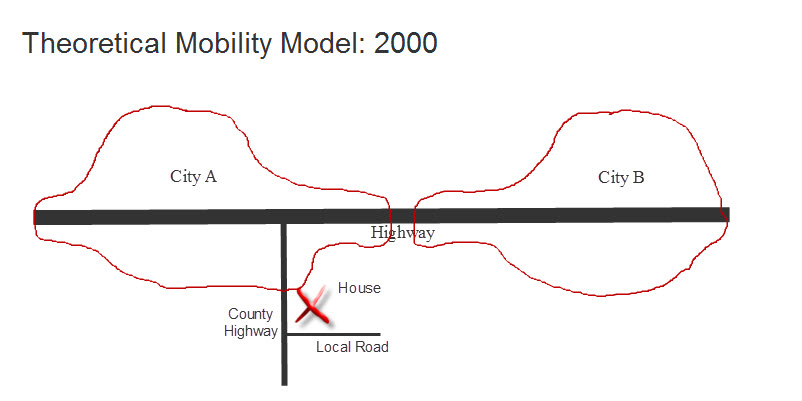

In our final "advancement", we take our lust for increasing mobility to its extreme and start connecting everything. The house in the middle of the country can now get to town taking a high-speed local street to a high-speed collector road to the highway. Because everyone drives everywhere, even for trips that used to be very local, and because we use a hierarchical road system that funnels all traffic to collector roads, the highway has to be widened.

It is easy to see how the costs of this system are so astronomically beyond our ability to pay. This is an immense amount of infrastructure to serve a population that is not proportionately greater than it was fifty years prior. Yes, we've grown as a country, but our cities have hollowed out while at the same time we've expanded into previously undeveloped areas (see Phoenix and Las Vegas as examples of the latter). Were this theoretical model attached to a real city, it is more than likely that the city would have dramatically more infrastructure today (and all the costs associated with it) while actually having less population.

Now here's where I get back to the mobility question. The costs are clear to see, but where is the corresponding increment of mobility enhancement? I don't see it. Yes, by opening up land along the highway to development we've given Wal-Mart a home and produced some short-term construction jobs in the process. Sure, by putting the country home in quick commuting range of City A and City B, we've made the owner rich by allowing him to sell to a developer who will make others rich by building them a sheetrock palace that will appreciate by 15% or more each year (until the market changes and they go underwater because thir home is dropping in value 25% each year), creating many construction jobs in the process. But how has this increase in mobility made us appreciably better off?

Or more precisely, what is the return on investment?

My final sketch depicts the Theoretical Mobility Model in the year 2000.

I don't quibble with O'Toole's numbers, and the arguments of mobility advocates in general, regarding the return on investment from mobility enhancements brought about by investments in the 1950' and 1960's. But since then, we have spent an untold fortune on incremental gains in the first and last mile of each trip without any obvious additional value to the macro economy. And, in the process, we've subsidized a living arrangement that has made our towns and neighborhoods fragile, dependent on too many variables beyond their control or even ability to influence.

If a little is good, more must be better? Not always for a Strong Town.

Additional Reading:

- Gridlock by Randal O'Tool in Google Books and at Amazon

- The cost of 40 seconds (January 14, 2010)

- The TIGER sleeps tonight (in Staples) (October 25, 2010)

- The ridiculous Old Economy project that won't die (November 29, 2010)

- Michele Bachmann and the St. Croix Bridge (March 18, 2010)

We're just three guys trying to change the world. Please consider supporting our blog and podcast with a monthly supporting donation of just $5 or $10. Every supporter we sign up gives us the resources and the credibility we need to reach more people with the Strong Towns message.