Small, Simple and Flexible

Cities need old buildings so badly it is probably impossible for vigorous streets and districts to grow without them. By old buildings I mean not museum-piece old buildings, not old buildings in an excellent and expensive state of rehabilitation–although these make fine ingredients–but also a good lot of plain, ordinary, low-value old buildings, including some rundown old buildings.

- Jane Jacobs in “The Death and Life of Great American Cities"

Yes. And, I would expand Jacob’s thoughts to say that we need buildings of all sizes.

I would like to personally thank everyone who attended Strong Towns on Tap last night. Also – a big thanks to Justin Burlise, Ryan Kelley, and all the speakers who volunteered to boldly stand up in front of such an unruly crowd of urban and transportation nerds; Emily Northey, Thatcher Imboden, Matt Steele, Sam Newberg, Max Musicant, Faith Kumon and, of course, Chuck Marohn.

Getting small-scale, incremental development is crucial to downtown and neighborhood vibrancy, and it’s something our local policy should strive for. The beauty of it is that it adds density while conforming to the existing fabric.

This is a standard Midwestern block. It has a dry cleaning storefront that hugs the corner and a few units on top. This is how urbanism will be accomplished in the next 20 years. We only have so many former industrial loft spaces near our town centers. New buildings will eventually have to migrate into our neighborhoods. This will probably need to happen outside of contemporary status quo; such adding flexibility to our code and going outside tradition lending methods.

To allow these small buildings to happen, we’ll need to be flexible and allow incompatible uses and we will need to be more forgiving of new buildings. Our codes will need to be flexible. They won’t always be perfectly in line with what a neighborhood may want. However, if given time and care, they can develop into great community places that people love.

Do buildings need to mold together? Do their forms need to match?

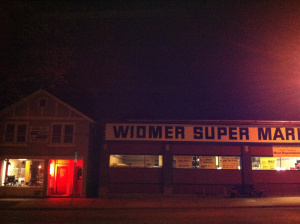

Incompatible uses? This St. Paul grocer is a single-story small “big box” style building that fits the streetscape and is, by and large, a great neighborhood market. It’s next to (and by next to, I mean, very close) what appears to be a duplex that has been converted into a retail front and upstairs office space (I believe there is an apartment, too).

Building a single-family style house next to a store like this, even under very loose zoning restrictions, is probably discouraged. Although it wouldn’t be impossible to do this in the neighborhood today, it probably wouldn’t be worth the uphill battle to get it approved.

The thing is, it works really well – even if it looks a slightly odd. The neighborhood gets a decent corner grocery store. A resident gets cheap office space near his house and a college student, young professional or senior can get an affordable apartment unit in a nice neighborhood across from a beautiful church, elementary school and community center.

The incompatibility can even be more blatant.

As long as you like noodle take-out, this is a win-win. And, let’s be honest – who doesn’t love that?

Even when the form is way out of scale, urbanism will adapt. The noodle shop and apartment pictured above is even more out of scale – a six story building butting up against a shotgun shack of noodle shops. But if the urbanism is there, these incompatible uses don’t matter. This noodle shop will benefit greatly by having six floors of students craving last-minute cheap food. All the while, the college students will benefit from having cheap food in very close proximity to their apartment. These examples work as long as there is a positive amenity that can be had by adding them to the environment.

The owner of the noodle shop and grocery store are not developers. They likely do not have the know-how or resources to run two businesses at once. They can, however, build (or renovate) small and simple. Unfortunately, this doesn’t happen to be within the scope of traditional lending.

We need flexible code zones. And, to be diplomatic – let’s start in areas where we’d like to see development happen (transit hubs, downtowns, neighborhood commercial nodes, etc.). Now, these new code-flexibility zones would need to be stipulations: it wouldn’t be “code free” per se, but more so a list of aims and objectives that would need to be reached. Aims and objectives would be things like:

1) good urban design,

2) incremental density,

3) transit-accessible,

4) walkability

In a sense, we’d be trying to achieve a version of form based coding, just minus innate building regulations. The codes I want to avoid are building codes, like “rooms larger than 250 sq ft must have outlets places 6 feet apart on load bearing walls”. The reason a code-flexibility zone is important is because it allows the small business to build or renovate their own space, without the help of an experienced developer. This may be the catalyst to help make that a reality.

The other element that needs to be considered is something more grassroots. The idea of a nation-wide infrastructure bank has been thrown around in the media, but it’s concentrated on large-scale projects like high-speed rail and highway projects. I’m interested in seeing it happen at a hyper-local level for small development projects.

Enter: NorthEast Investment Cooperative of Minneapolis. It’s a new “cooperative that will allow the people of Northeast Minneapolis to pool their resources and collectively buy, rehab, and manage commercial and residential property in the neighborhood.” It’s the first such real estate cooperative in the United States and something that should be closely followed.

They’re operating out of a uniquely middle-class, urban neighborhood. Being that is looked over by traditional large-scale developers, but doesn’t get the influx of city of non-profit grants to rehab its neighborhood. It’s a grassroots neighborhood real estate investment group with a target mission to improve the communities building stock. But, they also aim to turn a profit. I think this element is important and shouldn’t be overlooked. It helps get small-businesses and adjacent property owners onboard. It also creates an environment where all building owners and tenants in the neighborhood have a shared interest in its success. This might be the best way to go about getting small-scale, incremental development that can positively contribute to our urban environment.

This isn’t a call to end larger-scaled development. It is to say that we should think small, as these types of buildings can be much more effective at delivering positive outcomes, and more risk-adverse than one large development. It’s a call to say that small development and urbanism can be beautiful and functional.

___

I highly recommend reading “Good Enough Urbanism” by Andrew Burleson. It should be required reading.

“City codes don't matter very much in the end, the culture will get what it wants. If we want to make the most change in the most places as fast as possible, then we need to be all about good enough urbanism, because it's good enough to create the culture, because it's politically and financially feasible to do it right now, and because we can do it really fast - meaning we can do a LOT of it.”