Baldwin Park: A Test for New Urbanism

I had a chance recently to visit the Baldwin Park neighborhood in Orlando, Florida. Baldwin Park is a large mixed-use development based on the principles of New Urbanism, with a unique history. It is one of three neighborhood-scale, master-planned New Urbanist communities in the Orlando metropolitan area—the kind of ambitious mega-projects sometimes referred to as Traditional Neighborhood Developments, or TNDs. The other two are Avalon Park, in the city's far eastern suburbs, and Celebration, internationally famous as the "Disney town" for its Disney World-adjacent location and the role that that company played in its creation. All three were first envisioned in the 1990s and reached fruition in the early 2000s.

Former Naval Recruit Training Center, Orlando, now the site of Baldwin Park. (Source: Panoramio.)

Baldwin Park is unlike the other two in an important way: It is located not in the exurbs but within the city of Orlando, about 2 miles east of downtown. How was such a large piece of land in one of the country's fastest-growing cities left undeveloped until the turn of the 21st century? The answer is that Baldwin Park sits on the site of a former U.S. Navy training center, which was closed in 1998. Under the military's Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) program, which closed 20% of the nation's military bases in the 1990s, Pentagon officials worked with local planners to redevelop the site after the Navy vacated it.

The Training Center's closure, journalist Ruth Walker relates, left a "thousand-acre hole in the heart of the city". Orlando's planners wanted a neighborhood that would be an extension of the city, not a conventional suburban enclave. They held a design competition and recruited a team of acclaimed New Urbanist planners. The first residents moved in in 2002. There are now over 6,000 residents in Baldwin Park's 1,100 acres, and the commercial main street at the heart of the development is thriving after a rocky start, thanks to a large number of new apartments recently built in the town center.

Baldwin Park's history makes it an interesting place to study because it is extremely unusual for such a large tract of land so close to a major downtown to be redeveloped wholesale. This is a once-in-a-blue-moon kind of opportunity... and if you're a regular reader of this site, you might also agree that it's one fraught with peril.

At Strong Towns we're often critical of master-planned development. Communities built to a finished state tend to be fragile; their fortunes can change greatly over time as they age. They are susceptible to rapid economic decline because their buildings are all the same age, and will suffer physical decline (and become stylistically dated) at the same rate. The success of incrementally-developed cities, on the other hand, often hinges on the balance between old and new, something absent in place like Baldwin Park.

Faux-granularity: many small storefronts, but in a single building whose fate is controlled by a single property owner. (Photo credit: Andrew Price.)

Master-planned neighborhoods also tend to lack vibrant street life and complex social interactions in their public spaces, because those spaces weren't designed and tweaked through the sort of incremental, trial-and-error refinement that characterizes complex urban environments. In the best urban places, you have many different property owners and decision-makers, resulting in a deeply fine-grained mix of activities and environments. Master-planned developments can possess a certain sterility because decisions about the public realm, at least initially, are centralized in fewer hands.

And yet, at Strong Towns we're also quite positive about New Urbanism, a movement which is about a return to the time-tested principles that make great walking cities great. There is going to be new construction as long as people can make money from new construction, and isn't it best if that new construction applies design principles that we know from millenia of experience are germane to vibrant, productive places. What's the alternative, after all? Most likely, more of this:

Source: Johnny Sanphillippo

So how do we evaluate a place like Baldwin Park? How can we judge if it's a successful project, or a positive step toward a more livable and (fiscally and environmentally) sustainable city of Orlando?

My on-the-ground impression of Baldwin Park, as a pedestrian and a first-time visitor, is that from a design standpoint, this place works. Really well. I'll explain in the subsequent paragraphs why I think so.

Yet we also need to temper our expectations of the ability of master-planned developments, even one as ambitious as this, to have a transformative effect on a city. Baldwin Park exists in a metropolitan context, and its successes and failures are going to ride largely on how it fits into the city around it. This is a point that the most common criticisms of New Urbanism miss, and a point that is the primary reason New Urbanism is so widely misunderstood and derided.

Urban Design in Baldwin Park: A Photo Tour

Baldwin Park is designed on New Urbanist principles, mimicking the urban form of pre-automobile cities that were built around walking as the predominant mode of transportation. Incidentally, this means it also, to a large extent, mimics the design of nearby Winter Park (an inner-ring suburb with a traditional downtown that dates to the 19th century), parts of downtown Orlando, and the early 20th-century neighborhoods that flank downtown on multiple sides.

Car traffic is kept slow through narrow streets and parallel parking, and dispersed onto a well-connected grid instead of funneled onto a couple of arterial stroads.

There is a mix of building types, with greater height and higher intensity toward the core.

Buildings engage the sidewalk. The Gehl Door Average is high.

Even CVS, a notorious bad actor when it comes to pedestrian-oriented design, plays nice here:

The main commercial street, New Broad Street, comes to a head at an attractive, well-used lakefront park.

Land uses are flexible, and commercial and residential uses are not segregated from each other. The residential neighborhood a couple blocks off of New Broad contains a bunch of live-work buildings like these:

Finally, the single most important daily amenity for most people is not only present, but easily accessible to Baldwin Park's thousands of residents on foot or bicycle: A Publix grocery store lies just off New Broad Street at the center of the neighborhood, not on the outskirts along an arterial road.

This was a huge coup for the developers: chain grocery stores are often unwilling to do this, but Publix took a chance on Baldwin Park, and this location is now one of the busiest Publix stores in central Florida. The key? Baldwin Park's urban infill location. Ruth Walker explains that Publix was willing to bury itself inside the neighborhood because it had access to 100,000 customers within three miles, something that would never have been true in an exurban New Urbanist development like Avalon Park.

The urban design does make some concessions to Publix's parking needs:

But the store is accessible on foot via an attractive path, not a slog across a parking lot,

and the entrance is sedate and does not detract excessively from its residential surroundings.

One last thing about Baldwin Park: it's not an island. Its grid connects to the adjoining neighborhoods in many places, not just one or two. A look at Google Maps reveals this:

Baldwin Park works because it's an extension of Orlando. This New Urbanism works because it mimics the old urbanism nearby, and ends up expanding upon a cluster of walkable, bikeable destinations within a several-mile radius. That's really the idea of New Urbanism at its best.

A Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU) profile of the neighborhood describes the vitality of its public life:

Community life is active with holiday parades, porch sales, outdoor concerts and events. Halloweens are “crazy,” Grandin says, with each house getting 150 to 200 trick-or-treaters—some of whom come from other parts of the city. “People in Baldwin Park really do sit on porches and chat and talk and walk. I know everybody on my block and I’ve been there only 2 years. People make a point of introducing themselves.”

The connection between Halloween and walkable neighborhoods, incidentally, is not a new observation in the urbanist community. Baldwin Park seems to pass the trick-or-treat test.

Function, Not Just Form: Evaluating Baldwin Park

A design that mimics productive, vibrant places isn't enough to make a productive, vibrant place. The promise of New Urbanism is to rein in the car-dependence that has been so destructive to the prosperity and livability of American cities, and return us to places where a car is a convenience, not—as walkability guru Jeff Speck says—a prosthetic device.

We know that car-dependent development is bankrupting American cities, and we desperately need to return to building places that produce more value than it costs to maintain them.

Does Baldwin Park bring us closer to doing this? How should we evaluate it? What is and is not fair to expect from it? Some key questions might be:

Does Baldwin Park promote urban vitality?

Does Baldwin Park's design reduce car dependence?

How resilient and adaptable is Baldwin Park likely to be in the future?

Let's tackle these a bit.

1. Promoting Urban Vitality

Qualitatively, I'd say Baldwin Park passes this test, for the reasons I outlined in my photographic tour above. I haven't been there at different times of day and on different days of the week, but I saw a lot of people out and about, using the public spaces, using their front porches and balconies, and patronizing local businesses. The commercial district seems healthy with few vacancies. Anecdotes like the Halloween one above suggest a sense of community. If people are the indicator species of a successful place, I can assure you, you'll see more of them—outside of their cars, anyway—on a trip through Baldwin Park than most other Orlando neighborhoods.

2. Reducing Car Dependence

Does Baldwin Park's design actually result in reduced car dependence? The neighborhood had ample pedestrian activity on the nice Saturday afternoon I was there, but do its residents walk for practical trips, and not just recreation?

It's hard to find good data on this at a fine-grained level. We don't know how many residents walk to the grocery store, for example. We do have data on commuter behavior, thanks to the U.S. Census Bureau, and I think it's useful to compare Baldwin Park not just to the rest of the Orlando Metro in this respect, but to another New Urbanist development of similar vintage, Avalon Park.

Avalon Park was built around the same time as Baldwin Park, but on previously rural land at the far southeastern fringe of the Orlando metro area. I didn't make it out there for a visit, but here are some pictures courtesy of Google:

The superficial trappings are there: the mixed-use downtown with the walkable main street, nice parks, footpaths, houses that front the street...

But Avalon Park is completely isolated from the rest of the Orlando metro if you don't have a car. In fact, it's completely isolated from even the neighboring subdivisions to a truly ludicrous extent. A few years ago a Streetsblog post circulated about two homes with adjacent backyards which are seven miles apart by car. One of these homes is in—yup—Avalon Park.

Source: Google (via Streetsblog)

What can Census data tell us about commute mode choice in these two different communities, compared to the Orlando metro as a whole? How do Urban New Urbanism and Suburban New Urbanism fare differently?

For that matter, let's also throw in some Old Urbanism: the downtown neighborhood of the pre-automobile Orlando suburb of Winter Park.

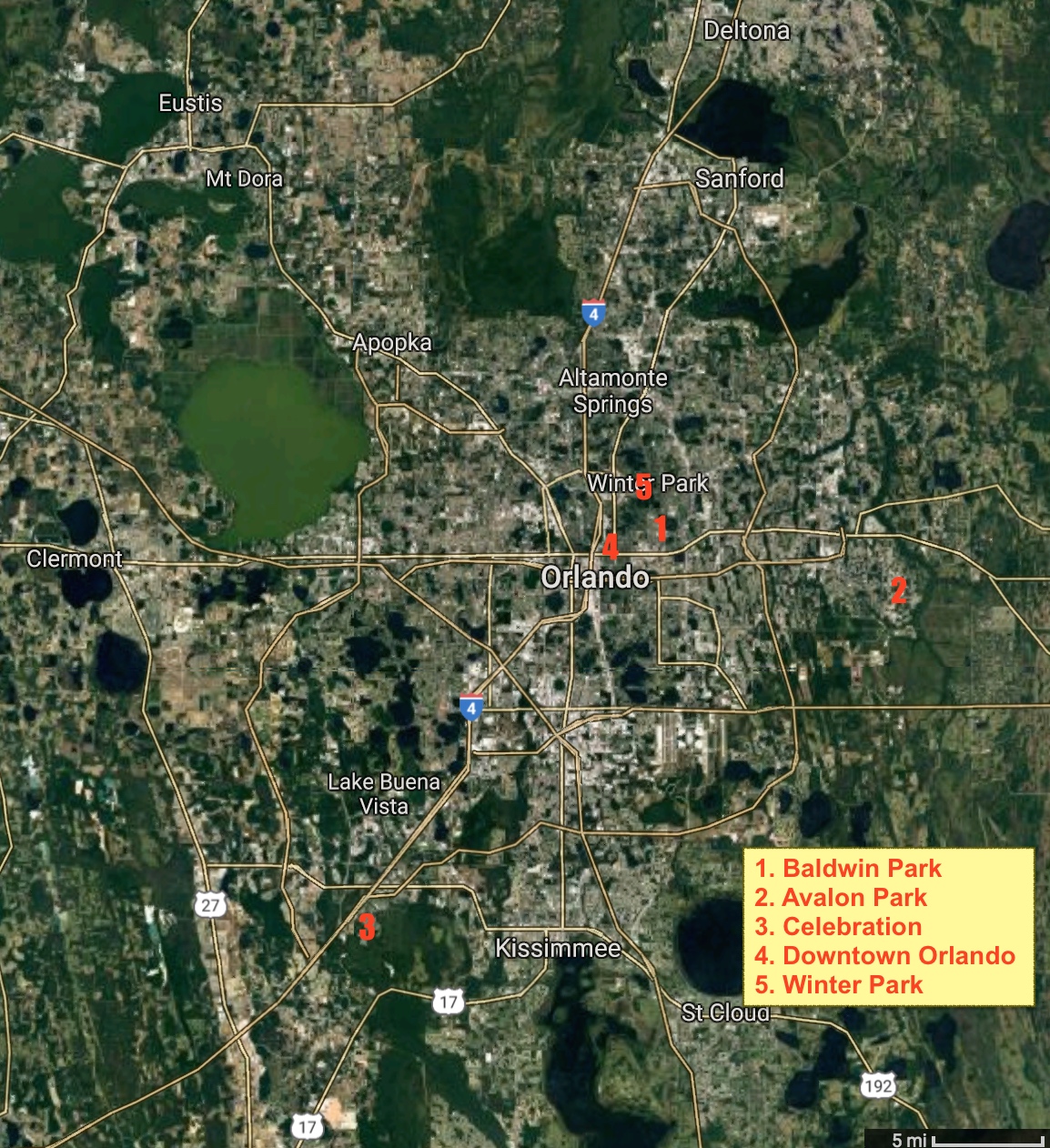

Here's a map for context of the various locations discussed in this post:

And here's how commute mode choice breaks down among these locations:

Data source: American Community Survey 2015 5-year estimates

Baldwin Park has significantly fewer residents, proportionately speaking, who drive to work than the metro area as a whole, while Avalon Park, the suburban New Urbanist community, is more comparable to the metro overall. This difference is explained almost entirely by people who reported to the Census that they worked from home, comprising 18.4% of Baldwin Park residents. A function of live-work studios and apartments above the storefronts? Without talking to individual respondents, there's no way to know for sure, but this seems plausible.

Commute times are also shorter for Baldwin Park residents, on average, though not quite as short as for Winter Park residents. Avalon Park, despite its New Urban, mixed-use design internally, comes in with the longest average commute times, and the greatest share of residents with a longer than one-hour commute:

Data source: ACS 2015 5-year estimates

Winter Park is the outlier in terms of both commute mode and commute length. It seems that it's hard to replicate the benefits—genuine mixture and complementarity of nearby land uses—of 100 years of organic urban growth in only 10 years. (I should note here that Winter Park is also home to a college campus, Rollins College, which may help partially explain its remarkably high share of residents walking to work.)

“One neighborhood is not going to make a huge dent in travel patterns in any city, because our lives are not spatially confined.”

So, what's the rub? Basically, metro Orlando is an extremely car-dependent place, and so Baldwin Park, which is just one neighborhood within it, is still a pretty car-dependent place. No surprise there. I don't view this as an indictment of New Urbanist design, however. The bottom line here is that one neighborhood is not going to make a huge dent in travel patterns in any city, because our lives are not spatially confined. Or, as Mathieu Helie's Emergent Urbanism blog states, "If you are building in a city at the metropolitan scale, you have to expect your potential residents to live metropolitan lifestyles."

The advantage of a Baldwin Park over an Avalon Park is that, if incremental infill is allowed to transform the surrounding neighborhoods with mixed uses and a greater variety of housing over the coming decades—and that's a huge "if"—you'll likely see compounding network effects lead to more walking and less driving. A constellation of vibrant neighborhoods adjacent to each other becomes something greater than the sum of its parts: something called, well, a city.

A place on the suburban fringe like Avalon Park? There's a lot of utterly car-dependent stuff in between it and the next nearest pocket of urban vitality. And it will simply never all be retrofitted. The money isn't there, let alone the political will. As soon as you want to leave the neighborhood, you have to drive, and that's likely to still be the case in 30 years.

3. Long-Term Resilience

How is Baldwin Park likely to hold up over time?

Property values right now, or tax base productivity right now, are perhaps not the best measure. Baldwin Park is still a pretty shiny and new neighborhood. Not only that, but it's in demand because of the scarcity of stuff like it. Like other Sunbelt metro areas, Orlando has a "shortage of cities", and this drives up the price of real estate in walkable neighborhoods. So of course Baldwin Park pencils out well right now. The important question is how it will fare over time.

Well, if the wisdom of "location, location, location" holds—Baldwin Park is centrally located in the metro area. If oil prices were to spike, Baldwin Park residents would suffer less, on average, than Avalon Park residents. Conversely, if a real urban renaissance occurs in Orlando, it'll spread outward from the longest-established hubs of walkability and street-level vitality: downtown and Winter Park. And Baldwin Park is close enough to benefit from that.

Many things can cause a neighborhood to decline over time. Like any master-planned development, Baldwin Park is at risk because of the uniform "newness" of its buildings, which over time is going to transform into uniform "oldness." But does New Urbanist design lend it any resistance to decline?

We can look at property value data during the most recent recession to garner some insights. Here's a graph of the Zillow Home Value index for Baldwin Park compared to the Orlando Metro as a whole:

And for Baldwin Park compared to its New Urban cousin, Avalon Park:

Compared to both the metro area at large and another New Urbanist community located on the suburban fringe, Baldwin Park home values spiked less during the last bubble, and fell less during the recession, remaining relatively more stable. This isn't a scientific conclusion by any means, but it's something.

If I had to venture a guess, this property-value stability has to do with both the inherently desirable location of Baldwin Park (near the city center), and its mixed-use, traditionally urban design. Baldwin Park has an eclectic variety of home types, from single-family detached to mid-rise apartment buildings, row houses, and live-work studios. And it has that main street with apartments above small storefronts. There's a reason the "living above the store" template is ubiquitous, internationally and throughout history. These designs work. They're adaptable and resilient. They're tested and proven.

Conclusion: To Evaluate Large-Scale Development, Ask The Right Questions

Master-planned New Urbanism get a lot of flack, and for some valid reasons as well as some misguided ones. I think some of the usual criticisms of New Urbanism are the wrong ones:

Is this only for rich people? This common criticism of New Urbanism mostly comes down to the fact that New Urbanist developments are newly constructed and often a type of neighborhood that is in scarce supply. These things make them in-demand and thus expensive. Nothing about the buildings themselves makes them "only for rich people" except that they're new: prices are determined by the regional housing market, not by the intrinsic characteristics of the housing. In fact, New Urbanist development is likely cheaper for cities in the long run than auto-dependent development, because less infrastructure is required per resident.

Is it phony and soulless? Lots of people say this about New Urbanism, too. They said it about Seaside, Florida, long before The Truman Show was filmed there. Celebration has been criticized as "deeply artificial." The truth is, you probably just think it is because it's new. When it's old, it will feel quaint and full of character, because the precise thing that makes places built in the 1920s feel quaint and full of character to us now is that they're old, and they remind us of old things. Quaint 1920s bungalow neighborhoods were assailed by angry neighbors as phony and soulless when they were built.

Now, the right questions, the ones which are going to matter in the long run:

Is the land-use pattern productive?

Is it conducive to car-free and car-lite living?

Does the design promote street-level vitality?

and, because we don't have a crystal ball and neither did the developers:

Is it flexible and adaptable?

This is the biggest factor that the massive scale of master-planned development works against. These places risk being "built to a finished state" and unable to change and adapt market conditions in the future. But a lot of that in Baldwin Park is not on the buildings, but on the planners. Will the city allow the flexibility in land use 20 years from now? Here's hoping.

I suspect some of my fellow regular contributors to this site would argue that Baldwin Park, or a site like it—perhaps the shuttered Ford Motor Co. plant slated for mixed-use redevelopment in my hometown of St. Paul, MN—should not have been master-developed at all. Instead, one might argue it should have been subdivided into lots on small, walkable blocks with flexible zoning, and left to the market to do its thing.

I disagree. The market has a lot of inertia to it—it tends to produce more of the same. This is true of the real-estate development industry as it exists now, and even more true of the risk-averse lenders who finance new construction. I think a place like Baldwin Park would have emerged as monotonous acres of single-family homes with big-box retail on the surrounding arterials. I might be wrong, but I don't have a lot of faith in the invisible hand to produce a radically different vision for a piece of land that size without some coordinating efforts.

For now, I'll say, you've got a good thing going here, Orlando. The good bones are genuinely there. The flexibility in uses is there, if you can keep it. It's a very livable place. For the rest, time will tell.

(All photos by the author unless otherwise indicated.)

Sarasota County, Florida, is planning to use hundreds of millions of dollars to subsidize housing. But this money isn’t going toward low-income housing — it’s going toward road construction for gated communities.