Cognitive Comfort and Visual Clutter: Is it Time we Started Regulating Style?

Design rules of thumb from Cognitive Architecture.

I was delighted to hear Chuck bring on Ann Sussman and Dr. Justin B. Hollander, the authors of Cognitive Architecture: Designing for How we Respond to the Built Environment, to the Strong Towns Podcast a couple weeks ago. I was a huge fan of the book, and even created a PDF with scans of sketches from it that illustrate good rules of thumb for the design of open space and streets. Everyone that has anything to do with urban design would do well to memorize the spacing rules for human habitat that they lay out in the book.

The reason their work is so groundbreaking is that it represents one of the final nails in the coffin for modernism in urban design. They touch on this tempting idea during the podcast episode: the belief that humans are robotically rational and that our environment can be radically re-engineered in ways (heretofore unknown) that will be more efficient, productive, and healthful.

What's wrong with that, you may be saying? Can't we always be thinking of new ways to design better places? Well, yes and no. Certainly we have a duty to strive for improvements in human living conditions. Modernist solutions, however, frequently transgress boundaries that were put in place for a reason. Let me explain.

As Chuck points out in Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity, there's a "spooky magic" to traditional practices in human societies. Many times, “the way we’ve always done it” seems to make no sense—until we stop doing it that way. Then we find out the hard way that certain limitations were put in place by those who came before us with good reason. (Discernment is needed, of course: traditions are not infallible, and certain practices and prejudices did need to go by the wayside.)

To illustrate the pitfalls of modernist enthusiasm, though, let the sad history of urban planning during the 20th century serve as Exhibit A. When Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright imagined a future of sprawling high-rise towers surrounded by parks and vast expanses of low-density detached homesteads, all accessible solely via personal automobiles, the one thing they weren't worried about was completely upending the way our ancestors had been building cities for millennia. As modernists, supposed heirs of the Enlightenment, their thought was that reason and technology could free humans from the restraints that spooky tradition and obsolete biology had laid upon their settlements up to that time. Density and walkability were seen as ancient curses that the clear light of rationality, with its attendant children in the technical sciences, could finally dispel.

And dispel them they did, most definitively here in North America, where less of the accumulated detritus (as they saw it) of the past stood in their way. As Chuck amply demonstrates in his book, we traded the hard-won knowledge from time immemorial about how to build cities for the utopian visions of a handful of early twentieth century intellectuals. The results, as the panel explained during the podcast, have been disastrous for human physical, mental, and emotional health. Almost like Frankenstein's monster, our creations have turned on us in ways we never foresaw.

The root of all this, the reason we threw out the baby with the bathwater when it came to the design of cities, was the lack of respect for convention that modernism prides itself on. A lack of caution. A lack of respecting limitations. Face it: we are biological organisms. Like all other such things on this planet, we have left and right lateral limits between which our flourishing is programmed to occur. To bulldoze those limits away when it comes to habitat design is as rash as trying to do the same with something like environmental temperature. Think we could survive for long on the surface of Venus?

Thankfully, it appears that more and more people are waking up to the gravity of the problem we face. In planning, "spooky wisdom" seems to be in vogue: just check out how many places have adopted form-based codes. New Urbanism is spreading like wildfire, and millennials and Baby Boomers alike are rediscovering traditional urban neighborhoods.

But one area in which I've not seen much of a paradigm shift away from modernism is in architecture, specifically in the area of style. People will readily acknowledge that planning modernism in the form of suburbia is a failed experiment at all levels: fiscally, socially, psychologically. But fewer will dare speak out against architectural modernism. Almost everything large-scale being built nowadays is in the form of a big shiny glass box. At best, you might get something with a little postmodern nod to traditional architecture thrown in, but nothing more. (Residential architecture is much more often "traditional," but in ways that make it seem like the architect had no idea what he or she was doing; see “the McMansion.”)

Ask the average person on the street why we should stand for this, and you'll get an answer like, "Well, beauty's in the eye of the beholder. We can't regulate style." But in the light of Sussman’s and Hollander's research, I want to submit to you all that, not only can we, but MUST we. And why? Because our subconscious desire matrix is not a blank slate we can remake at will. What do I mean?

Cognitive Architecture presents convincing evidence suggesting that buildings that look like faces "comfort" our subconscious. Buildings that don't have a face-like arrangement and symmetry oftentimes look jarring and unsettling to us. And guess what almost all traditional architectural styles have? These face-like proportions.

Image via Google Maps.

But there's something else traditional architecture invariably includes, which I have heard discussed much less frequently: visual clutter (Sussman and Hollander hint at this on page 128). Now, that may sound somewhat distasteful to you. Don't we all like sleek, clean, modern designs? We may value these designs for certain features they have, but the one thing they're not (at least in the traditional sense) is beautiful. When I say beautiful, I'm not trying to smuggle in metaphysics or religion. What I mean is simply that something is beautiful if it produces a certain mixture of awe, wonder, and comfort when looked at. This is different than thinking something looks “cool” or “interesting.” Modern architecture is certainly that. What I’m calling beauty is different, but I think if you’re sympathetic up to this point, you’ll know what I mean. Look at the Taj Mahal. I guarantee you'll feel slightly better just from looking at it. Try it with any universally loved older building. It can literally improve your mood.

Image via Google Maps.

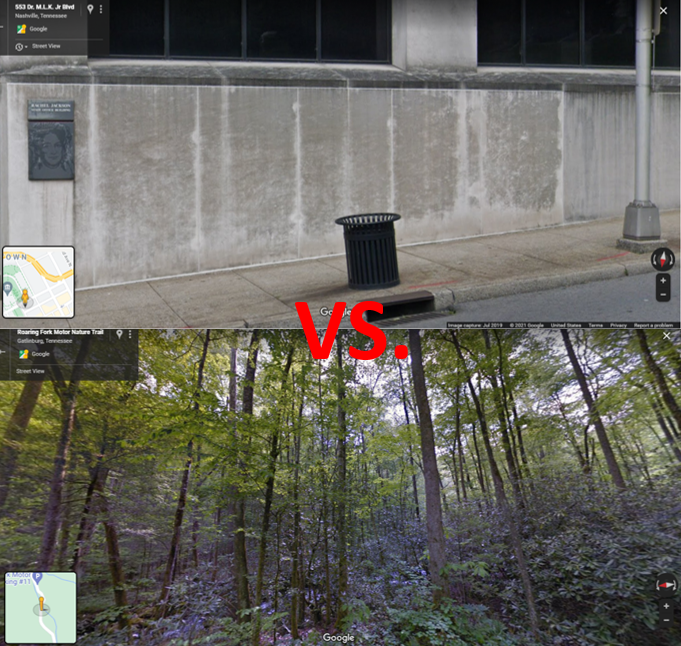

Again, a chief element of the appeal of these buildings is not only their face-like proportions, but also their sheer optical busyness. Why might this be? I want to venture, following the logic of Cognitive Architecture, that detailed visual patterns trigger the same response in our brains that looking at a beautiful woodland environment does. Trees are phenomenally intricate—thousands and thousands of leaves and branches, flowers, and fruits. There could be evolutionary reasons, such as the opportunities for shade and safety from predators that they may represent in our deep unconscious mind, as well. Whatever the reason, I’d be willing to bet that nine people out of ten would rather stare at a teeming natural forest scene than a blank wall.

State office building in Nashville vs. the Great Smoky Mountains. Images via Google Maps.

Clockwise, from top left: Detail from Notre Dame in Paris; St. Pancras Railway Station, London; Kandariya Mahadev Temple in India; Victorian home in Memphis, TN. Images via Google Maps.

So, in the absence of traditional architecture, what is the effect of all these blank, abstract, jagged protrusions surrounding us as we move through our environments? I'm no scientist, but my anecdotal experience tells me that it's similar to the effects a Wal-Mart parking lot (as Chuck would say) has on the human brain: stress-inducing.

But what can we do? I think the first thing is to popularize the type of research Sussman and Hollander are doing. We're finally finding a scientific basis for a lot of the pre-modern elements of city building that we might've formerly thought were arbitrary. Second is that we need to extend this conversation into architecture, not just urban design. This may sound like smug self-satisfaction, but I'm actually pretty proud of the way the planning profession has embraced things like New Urbanism and Smart Growth. It's safe to assume most planners these days are on board with the whole “traditional urbanism” program, at least in theory.

Architecture seems to be a different story. Too often architectural design seems to be the hijacked vehicle for various philosophies and ideologies that just don't translate well into the visual realm (modernist AND postmodernist). Research into cognitive responses to architecture will very likely reveal that these approaches are just as detrimental to our physical and mental wellbeing and communal life as 20th century urban planning was. I love Derridean deconstructionism as much as the next armchair philosopher, but let’s be honest: deconstructivist architecture is (quite by design) hard to even begin to wrap your mind around.

Walt Disney Concert Hall. Image via Google Maps.

All this needs to ultimately bleed into how we write our zoning ordinances. Plenty of communities regulate certain aspects of architecture: brick percentages, for instance. If we can regulate exterior building materials for reasons like raising property values and appearing more affluent, then why can't we mandate certain levels of symmetry and architectural intricacy for the sake of human psychological comfort? If we can mandate exact percentages of "glazing," why can't we require a certain percentage of ornament? This is not big government for big government's sake. This is one more step toward a physical environment designed for how the human brain is wired. This is not about preferring any one traditional style over another: it’s about using the principles that informed those styles to guide future creations. I’m not even sure how we would codify these elements in an objective way, but the point is, this is a conversation that’s long overdue. Let's take a few more bites of humble pie, throw out our mistaken notions and complacency, and start adapting our designs to the instincts of our species rather than the other way around.

Strong Towns member Dustin Shane, AICP, is an urban planner interested in exploring the intersection of philosophy, culture, and city building. He blogs about these and other topics at placeandtheory.com. He and his wife Maude are natives of Nashville and Middle Tennessee and enjoy fishing, local history, house spotting, and cooking.

When COVID-19 put her career on pause, opera singer Ally Smither found a new passion: fighting highway expansion.