Crossing the Street is Like Dodging Bullets

On September 8, Wiley & Sons will release the second book in the Strong Towns series: Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: A Strong Towns Approach to Transportation. The book centers on the story of the tragic death of a young girl in Springfield, Massachusetts. As the story unfolds, it ultimately is an explanation of who is responsible and what needs to change so we stop killing typically nine or ten children each day with our nation’s transportation systems.

Normal life need not be so dangerous.

In this story, “who” is responsible is less of a person than it is a mindset and an approach. That is, the standard approach American engineers and transportation planners use make our transportation systems unsafe. It need not be that way—it should not be that way—and the fact that making things safer would cost less and create better places to live only adds to the frustration.

Safe for a firing range. Not safe for a city street.

At basic training in the U.S. Army, we did an exercise late one night where I and my fellow trainees were prompted to crawl about 100 yards through a course containing barbed wire, trenches and other obstacles, all while machine gun fire blasted over our heads.

I remember looking up and seeing the tracer rounds fly from a tower to a target back behind the course. The bullets were well over our heads—I am sure I could have stood up and they still would have been well above me—but it was disconcerting nonetheless. While it was very unlikely that I was going to be killed by a stray bullet, it was far more likely that I would be killed by one than my friends who were safely back home.

Now, imagine my drill sergeant set up an M-60 nest in the middle of the street with a nice big target a couple blocks away, also in the middle of the street, and then began firing from one to the other. He'd hit the target every time (he's a pro) and so there would really be little to no risk of getting hit.

Here’s the question: Knowing you are extremely unlikely to be hit, would you walk along the street where this exhibition is taking place?

Probably not. I wouldn't. In fact, I wouldn't let my kids go within six blocks of this if I knew it were going on. Is that irrational? Statistically speaking it perhaps is, but when a small mistake means the difference between life and death, why risk it. What is the upside benefit that justifies the downside risk?

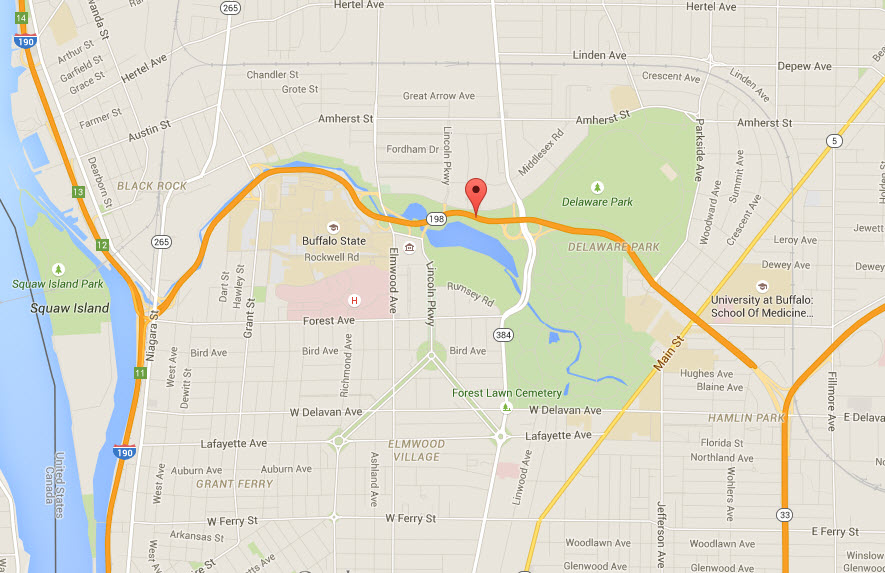

A few years ago in Buffalo there was a terrible incident where a car left the roadway and crashed through a park, killing a child and injuring another that had been walking there. Here's the news report:

A child is dead and another is in critical condition after a car struck them in Delaware Park.

The vehicle left the road while traveling westbound on Route 198 - the Scajaquada Expressway - just past Parkside Avenue around 11:30 a.m. It struck a three year old boy who was taken to Sisters Hospital, where he was pronounced dead at 12:15 p.m. His five year old sister is in critical condition at Women & Children's Hospital.

The two were out walking with their mother in the park, and one or both may have been seated in a stroller.

Changing the speed limit on the Scajaquada stroad.

Sadly, the unique thing about this incident is not the death of a child (children getting run down and killed by vehicles happens ALL THE TIME), the unique thing is the reaction to this specific tragedy. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo ordered the speed on Highway 198, which runs right through Delaware Park bisecting a number of community amenities and neighborhoods, to be reduced to 30 mph. His directive included the following:

While law enforcement agencies are still investigating the circumstances surrounding this terrible crash, it is clear that immediate action needs to be taken to improve safety for motorists and pedestrians on the portion of the Scajaquada Expressway that passes through Delaware Park.

For this reason, I direct you to immediately lower the speed limit on this section of the roadway to 30 mph, install speed messaging boards, and construct park-appropriate guard rails to protect pedestrians.

These actions are to be taken as the Department of Transportation continues to investigate long-term solutions to prevent further tragedies on this part of the Expressway.

This administration will continue to take every available action we can through engineering, education and enforcement to avoid crashes like this in the future.

This might seem logical to many of you, but I want to direct your attention to a nuance that demonstrates a confusion widely shared by those who design and manage our transportation systems. The governor directed the state’s department of transportation to: (1) lower the speed limit and install the signs that indicate that, and (2) build guard rails. In the language we use here at Strong Towns, Cuomo is saying (1) make Highway 198 more like a street and (2) make Highway 198 more like a road.

Stop firing bullets but also put up protective barriers.

The question we should be asking here is this: Does Buffalo want Highway 198 to be a road or a street? Is it a connection between two productive places (road) or is it a platform for building wealth (street)? If it's a road, which it seems like to me, then lowering the speed limit is the wrong thing to do. With the way this highway is engineered for high speeds, an artificially low speed limit will create a dangerous situation with some people driving the posted speed and some people driving the design speed. The larger that gap, the more dangerous it will be.

If it is a street and this is going to be a 30 mph stretch (which is still too fast), then the roadway needs to be redesigned so that the typical driver only feels comfortable when driving at safe, neighborhood speeds. That means narrowing lanes, tightening curves, and adding trees and other elements that create edge friction. Lowering the speed limit might be good politics—it is an action that can be taken immediately to give the veneer of doing something—but it's not good policy, even as an interim step, and especially not in the absence of any other design changes.

So, how about the guard rails? Again, if we're building a road where the goal is moving cars quickly, then the guardrails are a decent interim step, but long term, something more robust to keep people and traffic safely separated is necessary. Note that the governor called for "park-appropriate" guard rails, which I take to mean guard rails that won't harm the view of the park as seen from the driver's seat. If that's the case, then we're confusing the purpose of a park here just as badly as we're confusing the purpose of a highway. Urban parks are not aesthetic amenities for passing motorists. There's no return on that investment. Urban parks are meant to provide value—improve the quality of life—to people living within walking, biking, or transit distance of the park. If we're doing it right, that value should be reflected in the value of the tax base, the real creation of wealth.

All of this confusion goes back, of course, to the original bad decision to run a highway through the middle of a neighborhood. The impacts to the park, college, river, and all the housing should not have been so steeply discounted.

If Buffalo today were to eliminate Highway 198, that is, turn it into a true parkway with 20 mph neighborhood design speeds, I would applaud. I'm guessing that many in the neighborhood would, as well. After a transition, there would be abundant opportunities for growing their tax base and improving the community's wealth.

For a whole bunch of reasons, I doubt this will happen. It hasn’t happened in the six years since I originally reported on this issue. Highway 198 is still a nasty neighborhood stroad, degrading a community park and an entire neighborhood while providing minimal value moving insignificant amounts of traffic at nominal speeds, despite the high costs.

Even sadder, it’s no safer than it was when that child was killed. I would argue, it is less so.

If bullets were being expertly fired by a marksman at a target along Highway 198, New Yorkers would go berserk, even through the chance of accidental death would be minimal. I would not blame them for this reaction, but I'm completely baffled as to why they and the rest of us routinely accept much greater risk from drivers and their automobiles.

I also don't know why we continue to accept incoherent half-measures as a response. We need not.

If you would like to learn more about how we respond to bad transportation design, we have created some pre-order bonuses for people who purchase Confessions of a Recovering Engineer before September 8, including “30 Days of Confessions,” a video series I’m working on right now. We are also offering a steep discount on Aligning Transportation with a Strong Towns Approach, a Strong Towns Academy course providing a deep dive into applying the principles in the book. Both of these, and more, are available at confessions.engineer.

Charles Marohn—known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues—is the founder and president of Strong Towns. He is a land use planner and civil engineer with decades of experience. He holds a bachelor’s degree in civil engineering and a Master of Urban and Regional Planning, both from the University of Minnesota.

Marohn is the author of Strong Towns: A Bottom-Up Revolution to Rebuild American Prosperity (Wiley, 2019) and Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: Transportation for a Strong Town (Wiley 2021). He hosts the Strong Towns Podcast and is a primary writer for Strong Towns’ web content. He has presented Strong Towns concepts in hundreds of cities and towns across North America.