Love the One You’re With

This article was originally published on Strong Towns member Johnny Sanphillippo’s blog, Granola Shotgun. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author.

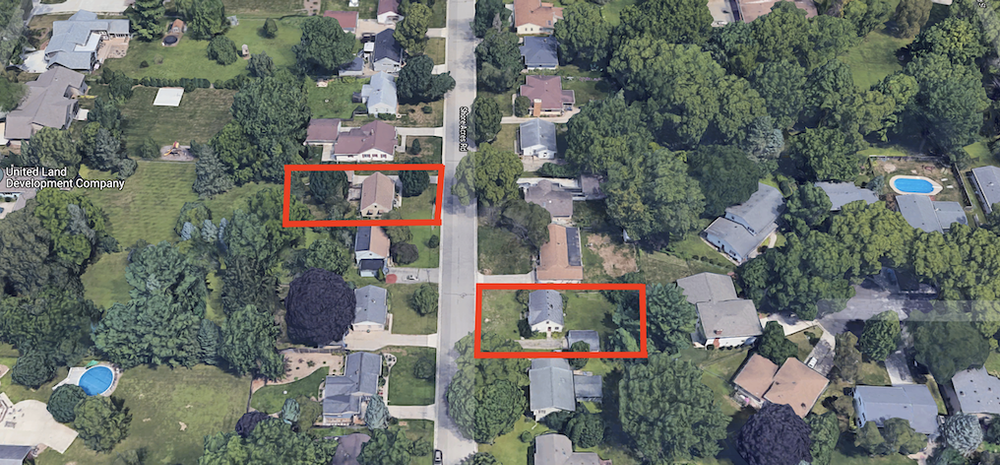

(Source: Google.)

In the last year and a half, I bought and renovated two modest 1950s-era homes in Madison, Wisconsin. Two beds, one bath, just under 800 square feet each—plain vanilla, nothing special. They were affordable, they were available, and they do what starter homes need to do: keep people warm and dry near good jobs, a medical center, a university campus, and an older downtown core which also happens to be the state capitol. The neighborhood is safe, clean, and it’s in one of the coveted premium public school districts favored by families with young children. These are the kinds of homes we need a lot more of, but no longer build.

These exact homes in precisely the same location could not legally be built today. These lots are 8,276 square feet (769 square meters), but the minimum allowable plot of land that can be built on now is 10,000 square feet (929 square meters). These homes have 768 square feet (71 square meters) of habitable space, but the present legal minimum for new construction is 1,200 square feet (111 square meters).

(Click to enlarge. Source: City of Monona.)

These restrictions have nothing to do with public health or safety, per se. They were enacted in order to screen out people who can’t afford larger homes on larger lots. It’s all a proxy for class and status. It might even be called social engineering. Any attempt to change these rules is guaranteed to bring out the townsfolk terrified of the wrong element. These protesters would inevitably include residents who themselves live in older, “substandard” homes, but that nuance would be lost on them as they lit their firebrands and sharpened their pitchforks.

Beyond the regulatory constraints, nothing that small is profitable to build. The national average for new homes is 2,400 square feet (223 square meters). What production developers really love to build are 5,000-square-foot homes with fat margins. You can’t blame them for building what sells at a better price. Companies that do attempt to build small and lose money don’t last long enough to create additional supply. It’s a tricky industry with harsh feedback. But there are side effects for society when smaller, cheaper homes are structurally unavailable.

I need to address the elephant in the room right away. I’m an evil out-of-town investor and these are now rental properties. Go ahead. Let her rip. Give me all your bile. I don’t care. I really don’t. I spent a couple of decades trying to figure out how to build new genuinely affordable market-rate homes like these and discovered the hard way that absolutely no one has any tolerance for that sort of thing.

What every institution in America wants me to do instead is participate in the financialized pyramid scheme that is the modern economy. So that’s what I’m doing. As the saying goes, “If you can’t be with the one you love, love the one you’re with.”

I’ll address another concern some of you may have. I didn’t “steal” this property from virtuous locals by outbidding anyone. In a very hot real estate market characterized by ultra-low mortgage interest rates, multiple all-cash offers, and no contingencies or inspections where homes sell in three or four days for well above the asking price…this place just sat there with no offers. The property originally listed for $230,000. After a month it dropped to $218,000. Two months later not one person was interested. That’s when I bought it for $205,000.

The people who sold this house left $25,000 on the table because they couldn’t be bothered to clean and paint the place before it hit the market. And potential buyers ignored this perfectly serviceable home in a prime location because they couldn’t see past the old crud and deferred maintenance. At the (then) interest rate of 3.5% and a 20% down payment, the mortgage on this place would have been a mere $736 a month. For context, the average rent on a two-bedroom apartment in Madison is $1,400 a month.

Keep in mind, this is in a neighborhood where the median home value is north of $365,000 and larger homes one street over have recently sold for as much as $900,000. Locals looking for affordable home ownership could have made this work, but it took a carpetbagger like me to see the potential. As my real estate agent Ben Anton likes to say, “Sometimes opportunity smells like cat pee.”

I reached out to the same group of local trades who had helped renovate the first house across the street in 2021. There was a two-foot square chunk of brick chimney taking a bite out of the already small kitchen. The chimney was only necessary because the ancient furnace was so inefficient that it vented hot gas out the roof. Once the furnace was replaced with a new high-efficiency gas unit, the chimney was removed and that precious space was liberated.

In a perfect world I would have preferred a latest generation, cold-climate electric heat pump instead, but the HVAC industry in Wisconsin isn’t on board with any such nonsense just yet. I’m not in the mood to go on a crusade over fossil fuels. (Perhaps a wood stove would make everyone happy.) When the old machine dies in fifteen years, we’ll revisit the situation. Until then, I’m content with clown shoes for my carbon footprint if it means I avoid an argument with the furnace guy.

The house had been built at a time when heating oil was basically free, so there had never been any insulation in the walls. Before new drywall went up, I requested rock wool be placed in the studs along with an appropriate vapor barrier. I’m aware that this is still wholly inadequate compared to the most advanced modern practices, but the real upgrades will only be possible when (if?) the old aluminum siding is taken down and replaced with a thick layer of exterior insulation and new siding. Maybe then the heat pump will make sense. But that’s for another day.

COVID induced all manner of supply chain disruptions and it was incredibly difficult to find kitchen cabinets. I eventually found a company in Pennsylvania that was able to ship some pretty good quality “RTA” (Ready to Assemble) cabinets made of solid wood rather than compressed dust. I was fortunate to have good people on site to do the work under less-than-ideal circumstances and I’m still grateful for their efforts.

Appliances were slow to appear during the pandemic, but they trickled in one by one throughout the winter. Maple butcher block counters were easier to install than custom stone, given the general labor shortage, and are better than plastic laminate. I like the warm natural look that balances the cold stainless steel. I chose some freestanding restaurant-style work benches for either side of the stove. They’re more durable than standard base cabinets and I like the industrial look. They were also much easier to source given the glut of restaurant supply equipment that piled up during the lockdowns.

The kitchen got new solid oak floors that match the original 72-year-old wood in the rest of the house. It was an additional expense, but with proper care it will last a century or more compared to the semi-disposable imitation flooring that’s usually part of such renovations.

(Source: Step Inside Media / Kristine Marks.)

These days, most people desire an open concept kitchen incorporated into a family-style great room. But this home simply didn’t lend itself to that kind of floor plan. The kitchen was boxed in by stairs on one side and the bath on another. Only a radical addition that enlarged the house off the back would work and that wasn’t in the budget. What we have instead is an updated version of a 1950s kitchen that functions well and looks good. The heavy-duty stove was a splurge, but it’s part of the marketing strategy for the property. That one item probably does more to attract quality tenants than anything else.

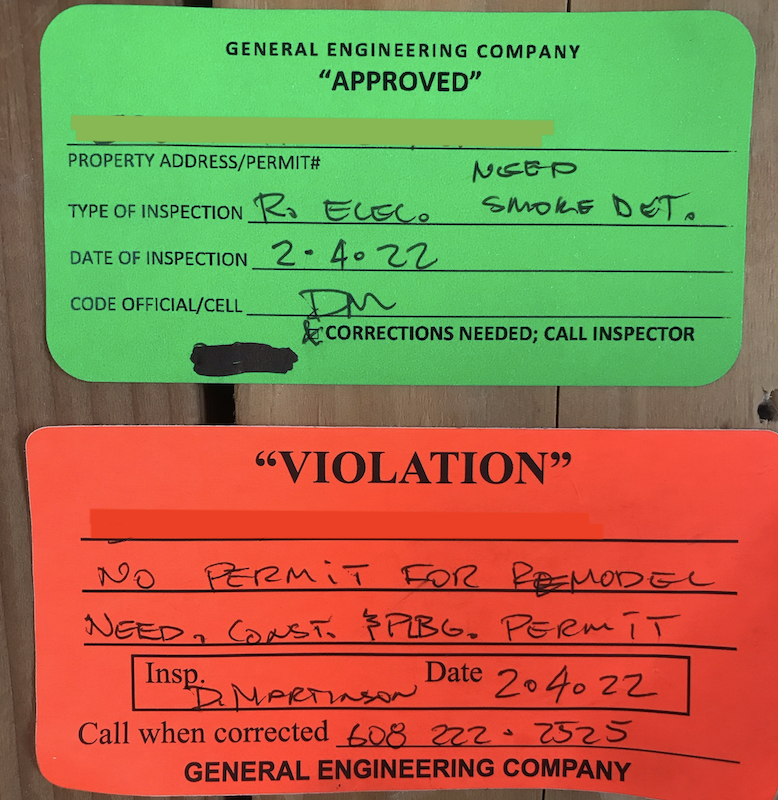

I have a strict personal rule born of pain from previous projects. If I have to ask for special permission from the authorities to build something—stop! It’s best to come up with a better plan. The old bath had some mechanical concerns that needed to be addressed. It was “legal non-conforming” the way it was since it was built before current rules were enacted. But if the bath were modified beyond a certain point, it would need to be brought up to modern code.

One particular problem involved the 24-inch (61-centimeter) minimum space needed between the tub and the edge of the toilet. That was going to be a huge can of worms since there was no room to move things around. One of the clever contractors suggested a Swiss wall-mounted toilet with a cistern that nested between the studs to make space. I’ve never liked overly complex solutions and this seemed like a future maintenance problem waiting to happen. But I agreed to the plan and it works really well. As a pleasant side effect, the little bath now looks significantly better.

(Source: Step Inside Media / Kristine Marks.)

Beige tiles and white fixtures are a bit dull, but they keep the room neutral and bright. Whoever lives here can personalize the space with textiles and accessories to express their individuality. Opaque film on the window provides natural light while maintaining privacy.

These are actually the original 1950s windows. Back in November of 2021, I paid for high-quality Andersen replacement windows for the entire house. They’re still in limbo eight months out. I hear the factory is having trouble getting wood, metal, and glass from their suppliers, along with labor issues. Finding a qualified crew to install them is the next drama. They’ll come when they come… At a certain point you just have to move on.

(Source: Step Inside Media / Kristine Marks.)

The living room and bedrooms were basically okay the way they were. The original floors were shined up, cellulose insulation was pumped into the wall cavities, the electrical system was upgraded, everything got fresh paint, and the windows will be replaced when they finally arrive.

(Source: Step Inside Media / Kristine Marks.)

The attic and basement got scrubbed clean, painted, and a new washer and dryer were installed. This process took months and filled two 40-yard dumpsters, but it’s all done now. These spaces could be retrofitted into proper habitable rooms at some point in the future. I’ve talked with a specialist who’s ready to install emergency egress windows in the basement when the time comes. Rough plumbing is already in place for a full bath in the attic whenever I decide to put in a dormer to raise the ceiling. This could become a four-bedroom, three-bath house without actually changing the building envelope all that much. But that’s for another day.

(Source: Step Inside Media / Kristine Marks.)

So here she is, all cleaned up. The lawn was a bit damaged during the renovation, but it’s coming back. The driveway needs to be repaved but I’ve yet to find anyone willing to take on the job in this economy. It will have to wait a while longer. I can’t say this renovation was easy. But I can state with absolute certainty that salvaging an old home is infinitely simpler than trying to build a comparable new house from scratch. That process induces madness and precipitates bankruptcy.

I’ve learned from past projects that people are perpetually outraged about everything all the time. Am I a slum lord lowering the quality of the neighborhood by profiteering and dumping unsavory tenants onto the neighborhood? Am I an elite gentrifier driving up home values and raising rents for hard-working people? Once again, I don’t care. I’d like to work toward solving practical problems in direct and tangible ways, but as far as I can tell, society doesn’t actually want to fix what’s wrong. Not my job. I’ve just signed a lease with a well-qualified professional couple for $1,800 a month. They move in next week, and I hope they’ll be happy in their new home. A lot of good people worked really hard to fix her up.