The Block Party

Up until a week ago, I’d never been to a block party. I must have walked by one once, or seen one on TV, because I had a pretty clear idea of what it would look like. Hoards of screeching children being herded by weary adults clutching red Solo cups; awkward small talk between strangers glancing at their watches; burned hamburgers, weak lemonade, and maybe a mime, or a clown making balloon animals.

But when I received an invitation to the block party in the Franklin to the Fort neighborhood in West-Central Missoula, it piqued my interest. The invite came from John Wolverton, an ardent Strong Towns member, so it seemed like a perfect opportunity as your Neighborhood Storyteller to write about a happening in my very own town; a storyteller’s version of investigative journalism, if you will.

I’m going to take a moment to clarify a few acronyms. I’m reading Dune right now, and find myself frustrated by all of the obscure terms, constantly flipping back and forth to the glossary, so I want to spare you that up front. Franklin to the Fort is the name of a neighborhood in West-Central Missoula, the city where I live, and it’s abbreviated as F2F. The neighborhood alliance and advocacy group who invited me to the party is called the Franklin to the Fort Neighbors in Action, and they go by F2FNiA. Okay, now I’ll get on with the story.

As I coasted into Franklin Park that evening where the F2F block party was in full swing, the first thing I noticed was the splash deck, alive with kids in swimsuits leaping through arcing jets of water, and one squealing toddler standing beneath the spray, fully dressed, including shoes and socks. The kids reminded me that even though I’d flipped the calendar over to September that morning, it was still summer. Had I not been on a mission, I would have joined them, shoes and socks and all.

The second thing I noticed were all of the wheels. Wagons, wheelchairs, bikes, trikes, scooters, strollers, and roller skates rolling up to, and through, the park. I was glad I’d ridden my bike. It would have been embarrassing to pull up to the curb in my Honda Fit in front of all of that human power.

The third thing I noticed was that I’d forgotten my bike lock. I resorted to the rookie move of looping my helmet straps through a chain link fence and buckling them around the bike frame. I don’t recommend this as a security measure, but it's better than nothing.

John and the F2FNiA members were easy to find. My first clue was a bunch of information tables under the picnic shelter, and a group wearing matching tie-dye t-shirts and name tags who looked unofficially official. My kind of people.

The F2FNiA’s information tables were crowded with community members. Poster boards dotted with colorful Post-it notes expressed things people liked about their neighborhood, and things they thought needed improvement. Seemed like an appropriate activity for a group described, in their own words, as “people coming together as neighbors to improve our health and well-being. We listen to each other, plan together and take action together around the problems that concern us.”

What’s not to like about that? Plus, I love the word “action,” especially in a group’s name. This reminds me of how much I dislike the expression, “sitting on a committee,” which feels like the opposite of action.

Among the diverse, multigenerational crowd milling about with ice cream cones, no one seemed to be bored, or glancing at their watches, and in the long lines at food trucks, people were conversing and laughing; no one shifting from foot to foot making painful small talk.

There was a bean bag toss, a giant Jenga, and a pile of panting kids who looked like they just completed a potato sack race. Tables were set up for kids—or anybody—to do crafts, and as far as I could see there wasn’t a mime or a clown in sight.

Right off the bat, John engaged me in a conversation about reimagining how we see traffic, parking, sidewalks, excitedly describing a reimagined alternative called a “living street,” or woonerf.

“It’s a Dutch concept,” John explained as he scrawled the word on a the back of a flier so I’d remember to look it up later. “The Dutch are pretty progressive when it comes to neighborhood design,” he said, and I imagined streets filled with bicycles and tulips.

John at one of F2FNiA’s tables.

At the other tables, I saw photos of the traffic circle beautification completed by F2FNiA’s Green Team division, and learned about a new mural project, slated to begin later in the month. When I picked up a flier for a community garden work day, a woman whose name I’ve forgotten but whose smile is still glowing in my mind said, “Don’t forget, you can always find us on Facebook!”

Though I proudly uphold my “Facebook Free since 1972” status, I halfway considered joining, just to keep track of what these people were up to.

John introduced me to Kate and Donna, two luminous members of the F2FNiA group helping out with the lawn games. The two seemed to me to be lifers; I imagined they were born and raised in the neighborhood, and had shared a lifelong friendship.

Donna (left) and Kate (right).

Nope.

“We just met during the pandemic,” Donna beamed, squeezing her friend’s arm, “not too long after I moved to the neighborhood.”

Kate, too, was a relative newcomer, just four years under her belt, but like Donna, her dedication to community seemed to be in her blood.

“I was a twin, after all, so I experienced community in the womb,” Kate winked.

Back in the height of the COVID lockdown in the winter of 2021, Kate wrote and illustrated a story, and posted copies along four different routes starting in the far corners of the neighborhood, taking the reader one page at a time, one block at a time to Franklin Park where the story ended, but the community engagement began. There, sitting in the park in the middle of January, in Montana, were members of F2FNiA providing a social outlet to ease feelings of loneliness and fear brought on by the isolation of the pandemic.

“It was a children’s story, but the message was really for adults,” Kate added, noting that children are often the best teachers for their patents.

This reminded me of the dad who I witnessed earlier reaching for a bottle of water off of one of the information tables. His daughter scolded, “Dad, we brought our OWN water from home, remember? The ocean doesn’t need more plastic!” The dad reflexively pulled his hand away from the disposable plastic water bottle, properly admonished.

“I’m actually a mechanical engineer,” Kate laughed when I asked if she was a writer by trade, but she also claimed the titles of artist, gardener, community enthusiast, and writer. I would add to the list of credentials, “maker of magic.”

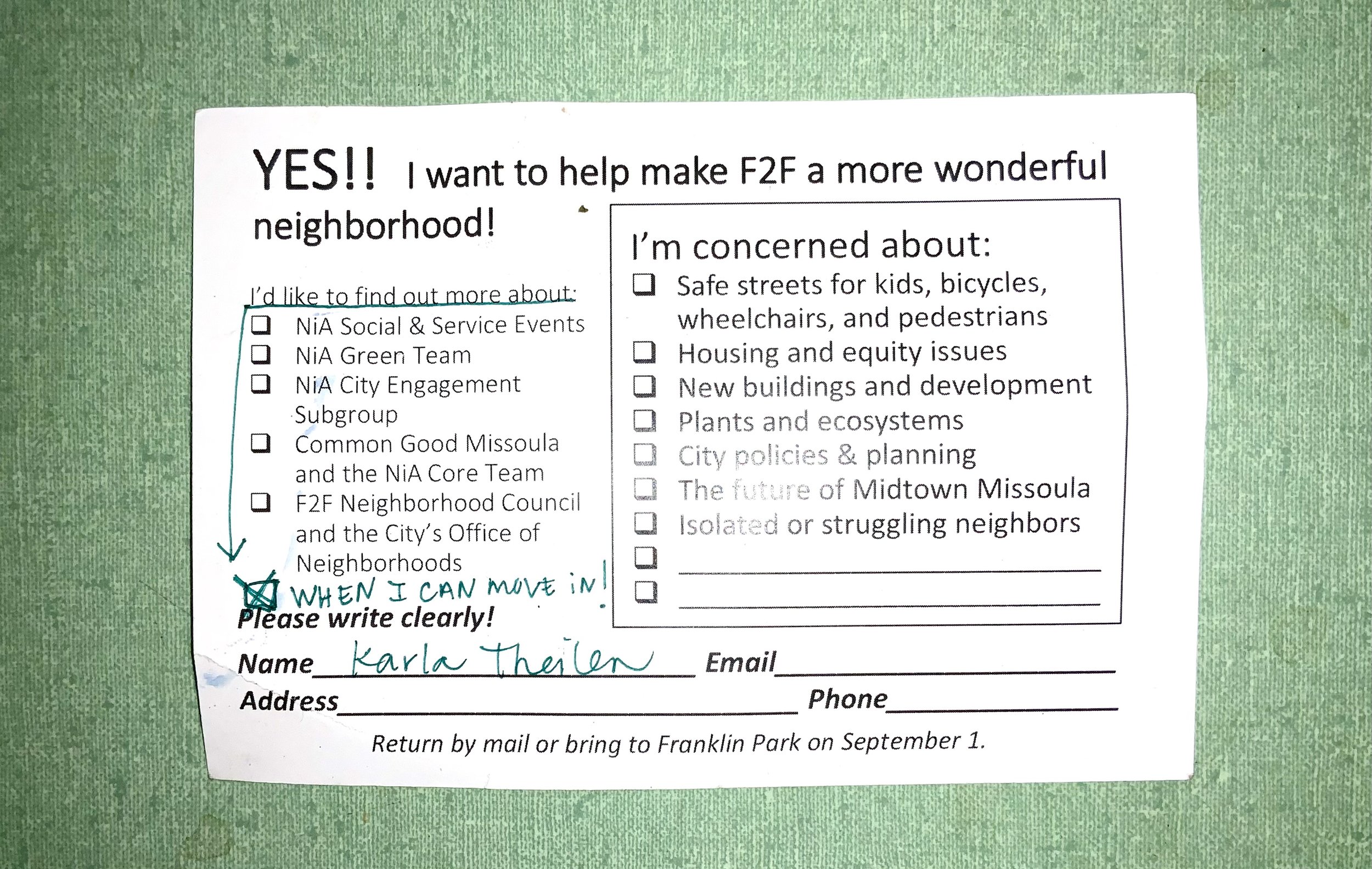

Toward the end of the evening, I picked up a card on an information table. There were boxes to check next to items you’d like to learn more about in the F2F neighborhood. The heading said, “I’d like to find out more about…” so I made my own write-in entry:

Where had F2F been all my life? This vibrant neighborhood tucked into the middle of my own city, a strong town unto itself, felt like another country, or a secret, landlocked microstate like Andorra, minus the duty-free shopping and gambling.

The sun was setting as I made my way to my bike, which was miraculously still dummy-locked to the fence. On my way, I bumped into one of the last members of the tie-dyed F2FNiA group I hadn’t yet met. Bill, the new pastor at the Methodist Church in the neighborhood, was a newcomer, too, even though I swore I knew him from somewhere. When he said he’d recently moved to Missoula from Mississippi, my mind went cartwheeling back to the summer of 1991, to Grant Village in Yellowstone National Park where all of the college-aged employees' name tags featured our first names and the state we were from. “Bill Mississippi??!?” I asked slowly, tentatively. When he said yes, I couldn’t help but shriek. We searched each other’s faces for the kids we were in 1991, which were surprisingly easy to find. We indulged in nostalgia until the dusk began to descend—like a bartender flipping the lights on as a signal to tell everyone it’s time to go home.

Bill and Karla.

Now that, dear reader, was an unexpected, but perfected ending to the night.

It might also be the perfect ending to this week’s missive, since I’ve developed a habit of telling you stories that end up connecting to something that happened thirty years ago. I guess it’s good to be consistent.

Oh, and if you haven’t figured it out already, I was dead wrong in my assumptions about block parties, at least this one.

And on the way out, I’m not gonna lie…I made a quick bike run through the middle of the splash pad. I couldn’t resist.

Read more of our weekly Neighborhood Storyteller columns here!

Karla Theilen is the Neighborhood Storyteller at Strong Towns. Karla is a writer, storyteller, and Registered Nurse based out of Missoula, Montana. Her penchant to explore wild places informed early career choices as a trail builder in the Grand Canyon, and a forest fire lookout in Idaho. Her current writing inspiration comes from a different kind of wilderness, navigating healing journeys with her patients in far-flung places where she works as a travel nurse. Her writing has been featured on NPR, and select stories and essays have been anthologized. She has been Facebook-free since 1972.