The True Cost of Debt in Atlanta’s Suburbs

Over the course of this week, my colleagues have trained their sights on Cobb County, Georgia. This seemingly unassuming area just to the northwest of Atlanta is like so many of North American suburbs—especially because, after a generation of seemingly unstoppable growth, it is beginning to fail.

Cobb County and its central city of Marietta have entered the third phase of what we at Strong Towns call the Growth Ponzi Scheme. After decades of building single family housing on large lots that don't generate the tax revenue they need to pay for their basic infrastructure, now Cobb is reaching for even bigger growth by inviting and subsidizing big box stores, large strip malls, and now professional sports franchises (yes, plural: baseball and soccer) to try to stimulate the local economy. While doing this, Cobb County is ignoring the needs of its poorest citizens and countless true opportunities for lasting growth.

The new Atlanta Braves Stadium, SunTrust Park (Source: Thechased)

Cobb County is no anomaly. Its level of debt service, economic disparity, and sheer dedication to building seemingly endless miles of asphalt are common suburban themes. But it is the scale of Cobb County's gamble that is unique: the county has made a proverbial "all in" bet on a big infrastructure projects, with its citizens on the hook for the bill. It is the nature of these proposals—“closed door deals,” without the chance for public input, and potentially violating transparency laws—that stings residents most. But what makes citizens feel most betrayed is the County's apparent willingness to throw libraries and parks—the cornerstones of any healthy community—right on the chopping block to get deals like these done.

The biggest culprit? Cobb County's proposed stadium project for the Atlanta Braves. “By the time they told us, it was a done deal,” says Guenevere Reed, activist and longtime resident of Cobb County. The $400 million in public funds put toward the stadium were not up for a vote, and there was hardly any opportunity for public comment.

The deal also came with some unconsidered costs—not the least which was the bill for the stadium's extensive parking. The stadium's placement next to two major interstates limited the amount of land available for parking, resulting in the creation of an $11 million dollar walking bridge over Interstate 285 to another new surface lot. And the original agreement also overlooked the cost of police presence, saddling the county, rather than the team, with this mysteriously unforeseen expense.

Adam Shields, an East Cobb resident, noted, “The actual costs were significantly higher than the initial proposals, and it appeared that the deal was done before it was announced.”

In the wake of these ballooning expenses, the continuing budget gap in Cobb County now seems like the opposite of the gift that keeps on giving. As my colleague Rachel Quednau noted, after using up a $21 million rainy day fund, the commissioners cannot seem to manage the rising costs of their infrastructure obligations. After threatening the closure of more than six libraries and several parks, they managed to close the remaining funding gap with a millage increase to the tune of $1.7 million.

This is partly because of Cobb and many other Georgia counties’ dedication to funding through SPLOST (Special Purpose Local Option Sales Tax), a 1% sales tax that can be used to fund a capital project, but whose revenue cannot be used toward operating expenses or maintenance.

Losing Their Libraries

The threat of closing public libraries and parks was met with public outcry and for good reason. Libraries are not only important community hubs for exploration and learning; they also serve as resource centers for the poor, offering free services that include high speed internet.

“Our services for job training can’t be overstated,” says Julie Walker, Assistant Vice Chancellor and State Librarian at Georgia Public Libraries. I asked Julie what the 407 public libraries in Georgia mean to the people they serve. She said, “Every one of them is the heart of their community. The best part of my job is pulling into the [local library] parking lot to see it completely full.”

Shields said, “I am a stay at home dad with a three- and four-year-old. We go to local parks or libraries at least three to five times a week. My two nieces play softball and so, during the spring and fall seasons, we attend a game at least once a week.”

The closures hit home for Shields and his children, with East Cobb included in the list of proposed closures. He said it would have impacted him to some extent, but the threat to poorer residents seemed even more acute: “It felt like most of the closures (but not all) were in low income neighborhoods.”

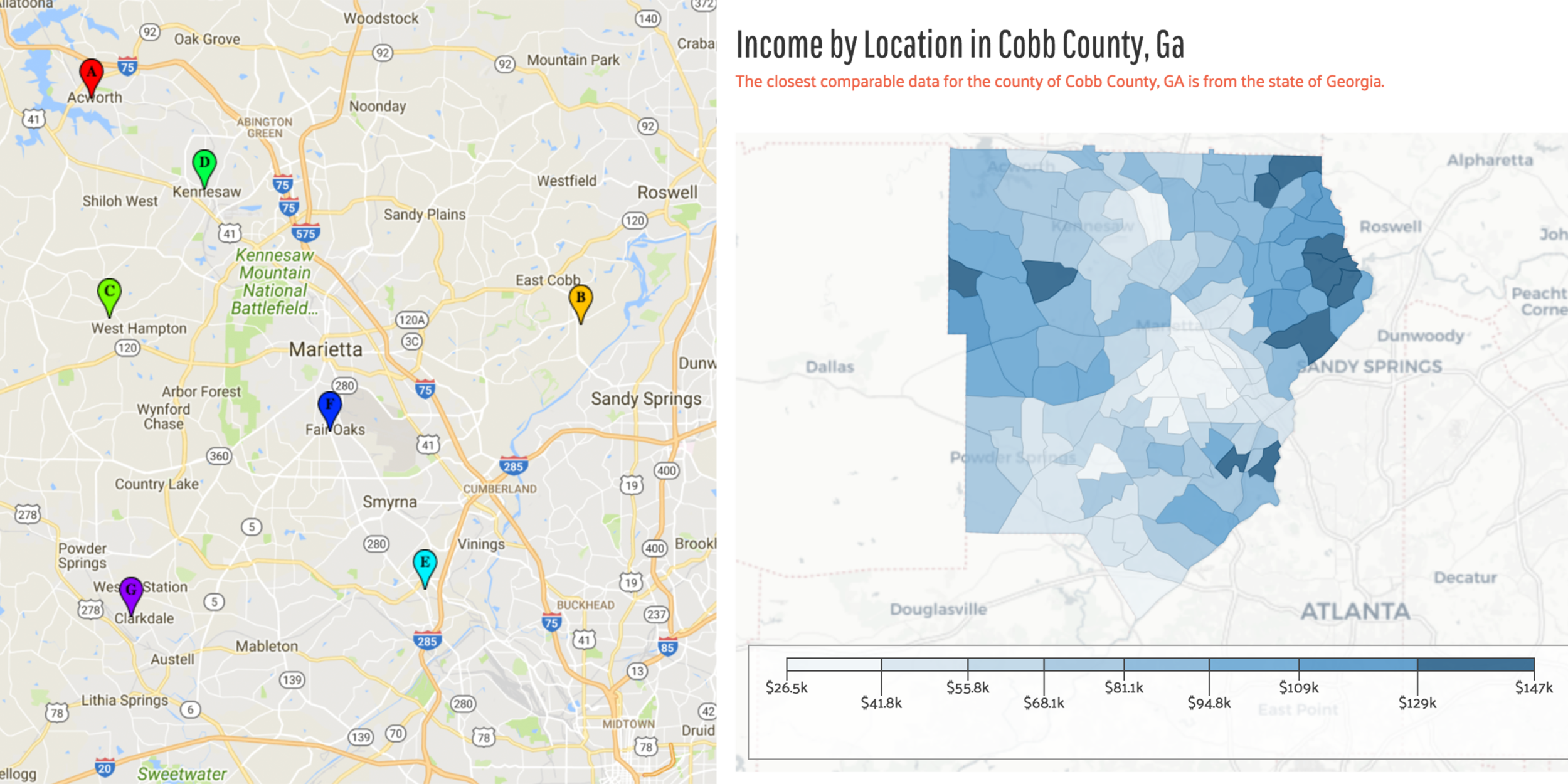

Adam’s inkling turned out to be correct. The map below illustrates the libraries that were proposed for closure. At a glance, they appear innocuously dispersed throughout the county, with the two listed in Acworth and Kennesaw (North Cobb County) being marked for consolidation rather than closure. But when juxtaposed against the county's racial and economic demographics (also shown below), they tell a different story.

Cobb Library Closings and Income Map

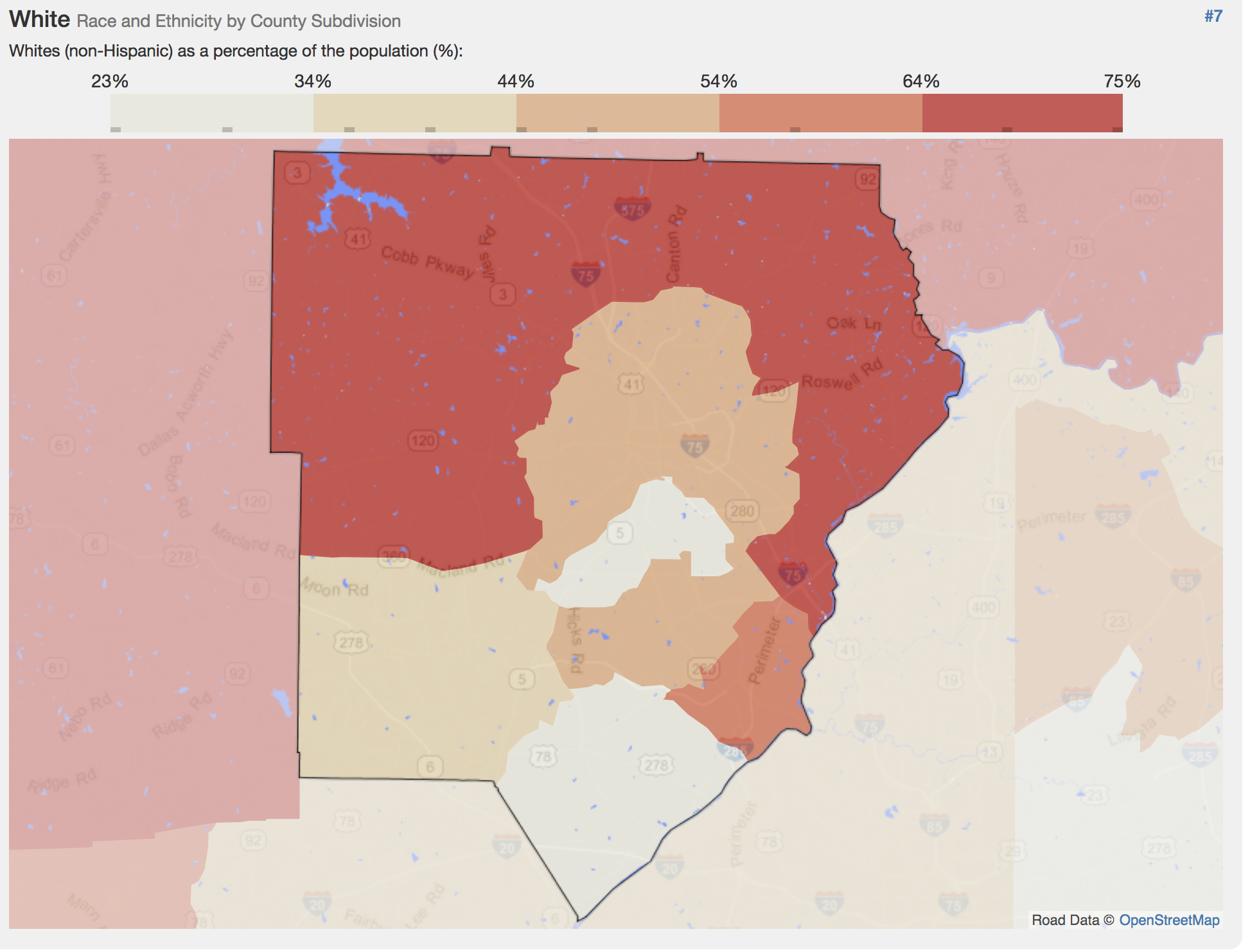

Cobb County's racial demographic breakdown.

Even without the closures, the library services in Cobb have already taken a hard hit in the ongoing budget crisis. Many libraries that used to operate from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. are only open from 11:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Some are closed for the weekend or midweek, like Lewis A. Ray.

“I loved the library,” says Reed. “I was rewarded ‘Geek of the Month.’ I used to take my kids to story time.”

“Sometimes elected officials think they’re outdated and that closing libraries would be a great way to save money. They don’t realize all of the services being offered,” said Julie Walker.

Cobb is not the only county in Georgia eyeing public services for cost savings. Bibb County, with Macon at its center, has until next week to pass a millage increase, or libraries, public transit, and parks and recreation will all be discontinued. It would be the first of Georgia’s 150 counties to be without any libraries. It would also result in close to 100 layoffs just for the libraries alone. “It’s such a horrendous, short-sided decision,” Walker says.

With the property tax hike come new promises. "I sincerely believe this millage rate will sustain Cobb County well into the future," Commissioner Chairman Mike Boyce said. "Maintaining this lifestyle in Cobb will be an investment for you, your children, and your grandchildren."

According to Cobb County Communications Director, Ross Cavitt, Boyce believes the increase is enough to keep all county services operating, and to begin the process of restoring some services cut during the recession. Yet no one I spoke with feels sure the county will not end up in the same situation as early as next year.

Cavitt also rightly noted how low the millage rate is compared to other counties in metro Atlanta. Unfortunately for Cobb’s poorest citizens, low taxes translate to far less access to public resources than in other corners of the metro area—especially the Atlanta region’s public transit system, MARTA, which operates in every other county adjoining Atlanta.

Cobb’s absence from the system is no accident. It has continually blocked efforts to join Atlanta’s system, and the history of this abstention seems to have, at least in part, been racially charged.

“My understanding was that the Braves Stadium wasn't going to be a burden on families and indeed is for some and a pain in the buttock for others. Not only do some residents get saddled with property tax burden, they have to deal with the traffic that goes with it,” said Chris Smith, another resident of Cobb County. Chris claims their property taxes have doubled since 2017.

It's also important to note here that Cobb County’s public transit is limited and slow. Kate described it in one word: “terrible.” In order to take a bus from the town of Powder Springs, where Guenevere lives, to the nearby city of Marietta, Google Maps suggests a 2 hour and 20 minute bus ride into Atlanta proper and back out without traffic. It also doesn’t account for the likely several mile walk you may need to take to the Powder Springs Park and Ride to board that first bus.

Cobblinc, the county’s transit system, is a bus system that operates with specific, limited destinations, mainly focusing on Marietta and Kennesaw State University.

A Changing Community

Ask many residents, and they're likely to tell you Marietta isn’t what it used to be. The once gleaming city that sits at the center of Cobb County is on the decline.

“This used to be a two lane road,” Kate Raybon’s father tells her as they drive through Marietta. Now it is a stroad covered with strip malls, gas stations, a Target. He tells her the area has “exploded.” But while development in the county has exploded, its wealth has not.

Kate’s family now lives in Asheville, and she is an Intern Analyst at Urban3, a geoanalytics firm we consistently source, including extensive reference in an earlier article in this series.

Marietta was once a center of suburban wealth in the 1960s through 1980s, but poverty has steadily grown. And there have been subtler changes than the widening roads and the strip malls that have sprouted across the physical landscape. According to Guenevere, the demographics have shifted in her nearly 20 years in Cobb. When she moved to the area in the 1990s, she estimates it was at least 75% white. Now it has become much more diverse—something that citizens like Guenevere value.

Marietta is the site of the new stadium and the biggest downtown area in Cobb County. It has more than double the rate of poverty in Cobb County as a whole—19.9% compared to 9.6%. Retail and food service account for more than a fifth of its employment.

Guenevere says many young people are moving out of the area due to the lack of jobs, including her daughter, who has relocated to Savannah. “Young people I know, like my sons’ friends, work at fast food restaurants, boutiques…” She blames the lack of employment services.

Many of Kate’s family members who still live in Cobb County commute to Atlanta for their jobs. Although only 20 miles, highway traffic makes the commute 1.5 hours each way. “They just deal with it,” she said. “I couldn’t.”

In theory, SunTrust Stadium was built next to the intersection of two interstates to alleviate traffic impacts during games, but so far, that hasn’t happened. In an attempt to alleviate congestion, Georgia is building an express tollway above the existing I-75 set to open later this year. Kate’s family calls this “the rich man’s highway.” For a fee, you can avoid traffic in and out of Atlanta.

Atlanta area freeway traffic. Source: Flickr. Creative Commons license.

The Braves are not the only ones to blame for the traffic. I-75 was well known for its congestion long before the new stadium made its way to the suburbs. Kate Raybon, whose family is originally from the area, says, “You avoid 75 at all costs.”

SunTrust Park also isn’t the only stadium Marietta has subsidized in the last few years. A $68 million dollar redevelopment bond was used to buy up land for a new practice soccer field. The facility sits on a site that was previously home to 1,300 affordable apartments, the residents of which were all displaced in a disturbing echo of mid-20th-century urban renewal projects. This same aggressive redevelopment tactic was used to bulldoze homes in order to make a new four lane connector road to alleviate traffic around the stadium.

Adam, whose wife is a school teacher, has noticed lower enrollment since the stadium's development. The demographics of her school have been changing, largely due to the shifting demographics of residents within several nearby apartment buildings. “Many of those apartment complexes have been renovating as a result of the stadium and increasing rents, which have displaced a number of students,” he says.

There are countless reasons this was a bad deal for all involved. And it's not about the sport itself. As a baseball fan myself, I feel it’s important to note that the people of Atlanta love the Braves. For Kate’s family, many of them fiscal conservatives, it is hard to navigate their feelings on SunTrust because they don’t like to see their government spend resources they don't have, but love baseball.

Adam adds, “The stadium is nice. I have attended one game and I have visited the complex to eat a couple of times… There is a public good with stadiums, but those that get the benefit are not lower income, but middle to upper income people. But all the people will pay for it.”

The situation in Cobb is a classic case of misplaced priorities. What Cobb County failed to budget into this proposal was the opportunity cost of what $400 million could have done for its citizens. It overlooked what this funding could have achieved had it gone toward job service training, mobility for the disabled, or revitalizing Marietta’s downtown. The more the area chases growth, the farther the Cobb County government departs from investing in citizens' needs and achieving real wealth.

(Top image source: littlestar19 via Flickr. Creative Commons license.)

Aubrey Byron serves as Membership Coordinator and Staff Writer for Strong Towns. She's a writer based in St. Louis, Missouri. Aubrey began engaging with public space as a cyclist and spends much of her free time trying to inspire more people to be comfortable on bikes through the advocacy of a local nonprofit, The Monthly Cycle. She is also passionate about outdoor adventure and reading.