Cobb County: Addicted to Growth

Imagine you’re walking through Target and you see a gorgeous flat screen TV. It’s the television of your dreams and you’re excited to buy it, but there’s just one problem; you recently lost your job, so money’s tight and you don’t have the cash on hand. You really want the TV though, so you put it on your credit card and head home with a big smile on your face.

A couple weeks later, after you’ve been enjoying the heck out of that new TV (while sitting at home, unemployed), you go to open your laptop and find that the whole thing has crashed. The help desk at the electronics store says your hard drive is toast. What’s more, your credit card bill just arrived and there’s no way you can afford to pay it. The next day, your car breaks down, but you have absolutely no money left to shell out for repairs…

What do you do now? Do you chide yourself for the impulsive TV purchase? Do you resolve to start saving more, start looking for a job in earnest, and maybe borrow a friend’s computer for your job hunt and bike to your interviews? Hopefully.

I can tell you one thing you wouldn’t do: Go out and buy a brand new phone, plus a new stereo system and couch. And then, for good measure, head to the mall and build yourself a fresh wardrobe—all while the credit card bills are piling up and your rent is long overdue.

Unless you wanted to be completely broke within days, you wouldn’t do any of these things. Even though these purchases might provide a temporary high and give off an illusion of wealth to your friends and neighbors, you’d be downright foolish to invest in them when you can’t even pay your electric bill.

And yet, that’s exactly what most of our municipalities do every year. They go into massive amounts of debt to buy shiny, new things, while potholes go un-patched, firefighters go unpaid and bridges begin to crumble. This decline isn’t always apparent and may only show itself in certain pockets of a community—but it grows and spirals, until eventually, it takes over.

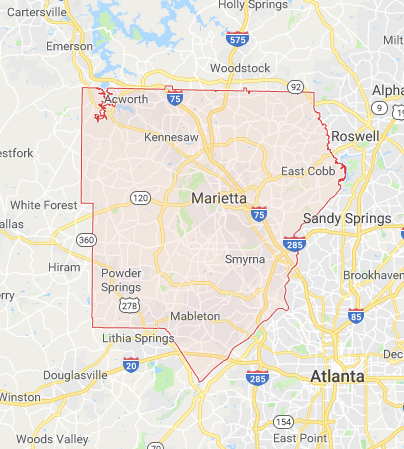

Growth in Cobb County has spread from Smyrna to Kennesaw to the far reaches of the region. Over the last half century, farmland and small towns have been replaced with strip malls and stroads.

The trajectory should have been obvious from the very beginning, when the municipality failed to make a plan to pay for the inevitable maintenance needs of all the new infrastructure they'd planned to build (and most municipalities do). But when failures in basic maintenance begin to become widespread—so widespread, in fact, that the community starts to notice—city leaders often just express confusion about how this could have happened.

This pattern of decline we call the Growth Ponzi Scheme is more evident than most places in Cobb County, Georgia. And that’s where our story begins today.

Addicted to Growth

Cobb County lies on the suburban fringes of Atlanta, and it’s the result of a development pattern that has spilled further and further outward as more people moved into the area and wanted their own single-family homes and yards. Despite the fact that municipal budgets were overstretched, Cobb County suburbs kept constructing new roads and pipes and electric lines to service the new homes — all the while building in a style with very low return on public investment (i.e. a bad tax value per acre ratio).

Like an addict whose use is spiraling out of control, these communities kept reaching for “just a little more growth” and “just a few more development projects” to get them through the next budgeting period, begging other sources (particularly at the state and federal level) for money to feed their habit. And all the while, these municipalities were promising that that last hit of growth was just what they needed to get through the day. Everything else would work itself out later.

The most recent example of this bizarre spending pattern is Cobb County’s decision to construct an enormous new baseball stadium for the Atlanta Braves—essentially buying the franchise from downtown Atlanta—at a cost of about $300 million in taxpayer dollars. Stadiums are notorious money-sucks whose proponents consistently overpromise and under-deliver on economic growth and revenue deriving from their development. For Cobb County, the situation is likely to be no different, and the financial gamble is falling largely on taxpayers.

A 2017 article in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution quotes Cobb Chairman Mike Boyce as saying the stadium project is a “deal too good to be true.” Meanwhile, South Cobb resident Guenevere Reed asks, “It seems like money is raining on Cobb County, but only when it comes to the stadium. We’ve been duped.… all the money that place is getting and we can’t get a bus from Six Flags Drive?”

Cobb is desperate for new growth—even in the form of a speculative gamble like the Braves stadium—because their development pattern has left them dependent on that growth to cover the liabilities associated with their unproductive land use. In this fragile state, it’s especially foolish for the municipality to be spending so much on new amenities while many of its residents can barely get their basic needs met.

From Affluence to Poverty: The Classic Suburban Story

Perhaps part of the reason for this extravagant attitude is that Cobb continues to see itself as it used to be. Back in the 1950s and '60s, Cobb was a predominantly affluent county where the wealthy fled the city for a quiet, upscale country lifestyle. But in recent decades, as a 2014 feature story about Cobb County in Politico explains, “suburban poverty exploded.” The suburban region “now finds itself facing an epidemic of the very poverty its residents were determined to avoid when they moved out of the city.”

This is the story of so many American suburbs. Developers plat new streets and offer big promises of modern construction in upper class neighborhoods. People move in and start their lives. Fast-forward three decades though, and the sheen on those brand new homes and manicured front lawns has faded, the streets are growing patchy, and the schools and shops need repairs. But the money to make those fixes is gone. In truth, it was never really there.

For just one example of this fall from affluence, let’s take a look at the town of Marietta, which sits in the middle of Cobb County. In the '60s and '70s, it was a wealthy, popular community, but once the shine wore off, rich residents got out, moving farther afield, and leaving poverty and decline in their wake. In 2015, Marietta decided to spend $65 million in public dollars to buy up and bulldoze 1,300 units of affordable housing in the municipality. This demolition was justified because the apartments were labeled “dilapidated” and “high crime.” This decision was not only a shameful attempt to force poor people out of Marietta, but it was also particularly strange since these apartments were, not long ago, filled with well-off residents and viewed more positively by the community.

Welcome to Marietta — home of the famous Big Chicken KFC restaurant, and miles and miles of stroads, fast food restaurants and other low value, auto-oriented development. Is it any surprise that this spread out region can't be financially sustained?

Today, a full 88% of poor people in the Atlanta metro area reside in the suburbs. 86,000 people in Cobb County alone live below the poverty line. Suburbia is a particularly despotic environment in which to be poor. Services that are easily accessible for low-income residents in a city—things like busing, job training programs and homeless shelters—are few and far between in many suburban areas. What’s more, this poverty often goes unseen and unnoticed by the majority of suburban residents. Your little cul-de-sac might look just fine and your neighbors might all own expensive cars, but travel down the road half a mile, and you’ll find crumbling sidewalks and people who can’t even afford a car at all.

When the creeping stain of poverty grows truly noticeable, though, the residents with money head to greener pastures—the next hot new suburban development on the edge of the existing one—taking their tax dollars with them and leaving their old community to suffer even further. According to an Atlanta Journal-Constitution article from last December, Cobb is now facing “a $30 to $55 million budget shortfall after raiding $21 million in rainy-day funds to plug a gaping hole in the 2018 budget.”

The fiscally conservative, conspicuously wealthy image of Cobb County is fast being revealed as an illusion.

A Downward Spiral

What does this downward spiral look like in practice?

In Cobb County, it means library closures. It means parks shutting down (while the county bafflingly chooses to go $27 million in debt to buy more parkland). It means higher costs for small business licenses. It means new fees for using community resources like senior centers and new taxes just to pay for basic police services. Any of these changes would be harmful in and of themselves, but when you consider the fact that resources like libraries, senior centers and small businesses help connect people to employment options and financial stability—well, then they are really shooting Cobb in the foot.

And for what purpose? To build a new stadium? This sort of decision-making defies the most basic logic. An elementary-schooler learning addition and subtraction for the first time could tell you the math doesn’t work out.

So why do places like Cobb County keep spending more and more, while their municipal budgets go further and further into the red?

This week at Strong Towns, we’re going to dig deeper into the tale of Cobb County and the math behind it. Pay attention to this story, because chances are, it’s the story of your city too.

Cobb isn’t an anomaly; it’s a poster child. Stay tuned for the next article in this series tomorrow.

(Special thanks to Bo Wright for his contributions to this piece. Top photo of a Cobb County landmark, the Big Chicken, by justgrimes)

Rachel Quednau serves as Director of Movement Building at Strong Towns. Trained in dialogue facilitation and mediation, she is devoted to building understanding across lines of difference. Rachel has served in several different positions with Strong Towns over the years, as well as worked for local and federal housing organizations. A native Minnesotan and honorary Wisconsinite, Rachel attend Whitman College for her undergraduate and received a Masters in Religion, Ethics, and Politics from Harvard Divinity School. She currently lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with her husband and two young children. One of her favorite ways to get to know a new city is by going for a walk in it.