Cities Are Complex. So Why Do We Treat Them Like They're Merely Complicated?

There’s an old Calvin & Hobbes comic I love. In the first panel, imaginative six-year-old Calvin gulps down a glass of water. But he has a terrible realization. The human body is 80% water, and he’s just pushed it over the limit. Acting as his own narrator, Calvin says, “Now it’s too late! By drinking that extra glass of water, Calvin has upset that precious balance! He is now 90% water.” We watch as Calvin dissolves into a puddle on the floor. His only hope is to get to an icebox and freeze himself solid until he can get medical help. He says: “Unfortunately, as a liquid, Calvin can only run downhill! Can he make it? Can he make it??” I won’t give away the ending.

I was nine-years-old when this comic first appeared in the Sunday newspaper. I was a daily reader of the funnies, and Calvin & Hobbes was my favorite. Yet this particular installment stuck with me in a way probably no other comic strip did. It planted in my young brain questions about how the human body and the world around me maintain their structural integrity. Could this next glass of water put me over the edge? What was stopping me—or my dog, our chickens, or my little brothers (if wishing made it so)—from liquifying, spontaneously combusting, or slowly drifting into the air as gravity weakened? The world was more resilient than I’d appreciated...but it was now more vulnerable too.

This comic strip came to mind again this week as I was trying to describe the difference between complex systems and systems that are merely complicated. You’ll see why in a moment.

Cities are complex places. It may seem like an obvious statement, but in fact the North American development pattern—the way we’ve grown towns and cities since at least World War II—doesn’t treat cities as complex, merely as complicated.

What’s the difference, and why does that difference make a difference?

Something that is merely complicated is knowable—at the very least by experts and technicians—and predictable; it is incapable of evolving, and so it is ultimately fragile.

Complex systems are less predictable and ultimately unknowable, which should inspire a little more humility in us. They are adaptable and more resilient, though not, as we’ll see, indestructible. Complex systems are also “emergent,” as Strong Towns president Chuck Marohn described in a seminal 2014 article:

A complex system is one that emerges from a collection of interacting objects, each of which experience feedback, are free to adapt their strategies based on their experience and are influenced by their environment. Pause for a moment and consider each of those insights.

A complex system emerges, it is not imposed but instead appears, as if by magic. It is a collection of interactions between objects, any one of which we may understand but, when examined over time, very quickly become unpredictable. This is because these objects experience feedback; they learn from what they experience and change their behavior accordingly. And finally, these objects are impacted by outside events which they do not control or even necessarily fully understand.

Here are a few side-by-side juxtapositions of the complicated and the complex:

Complicated: Cornfield

Complex: Forest

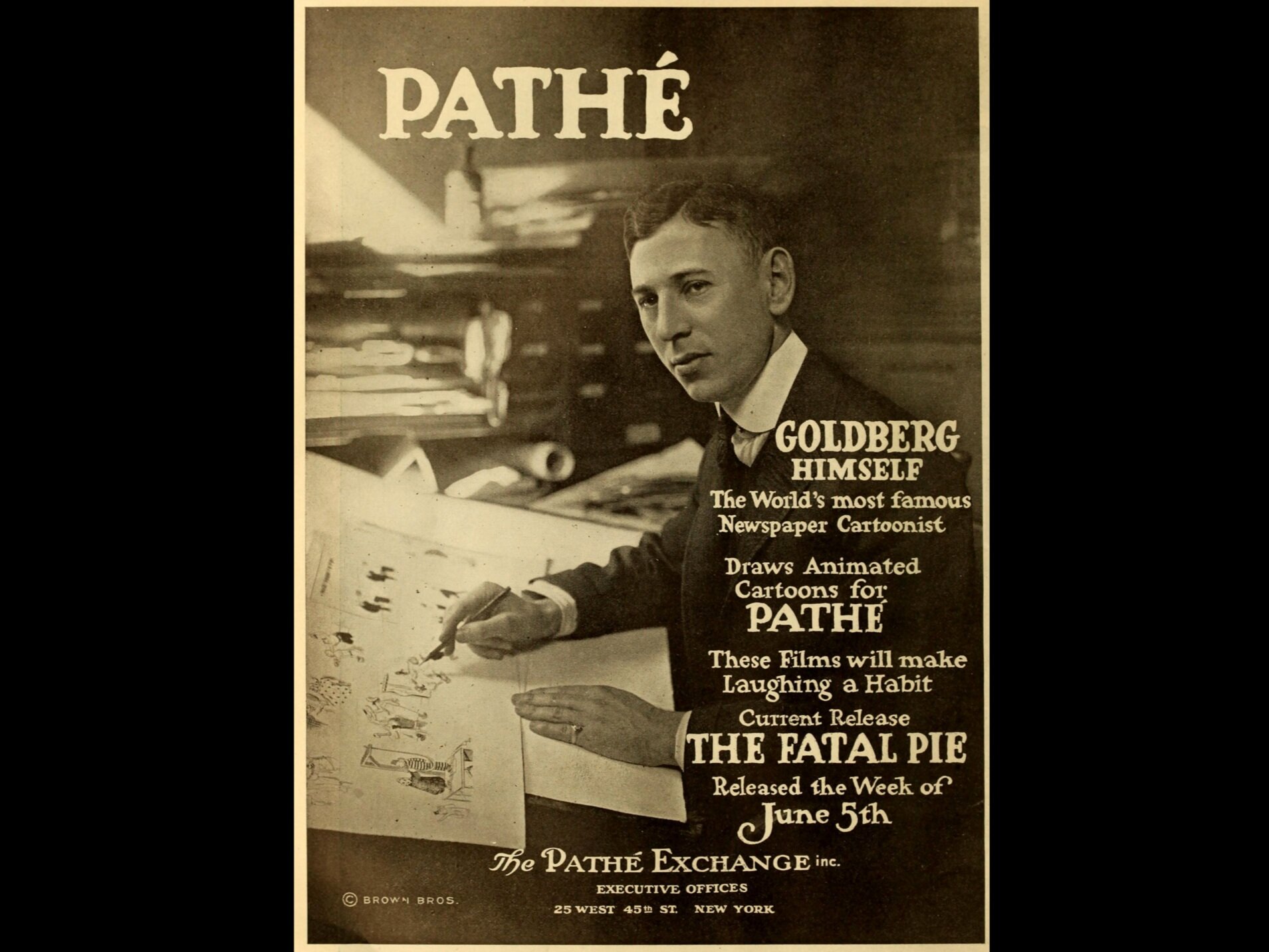

Complicated: Rube Goldberg Machine

Complicated: Suburban Development Pattern

The traditional development pattern is one that developed over thousands of years. It’s the spooky wisdom of city-building that we inherited from our ancestors. Cities built according to these time-tested insights have the capacity to experience and incrementally adapt to feedback. They can grow, contract, evolve, and heal depending on whether times are good or bad.

Not so for the suburban development pattern, which is built to a finished state, all at once, and frozen in place by strict zoning laws. If something breaks in the system—due to a terrible pandemic, say, an economic downturn, or both—the complicated city isn’t allowed to adapt. This is why we say towns and cities caught in the Suburban Experiment are designed to decline. “We have come to see the stagnation and decline of our blocks and neighborhoods as a normal part of the development process,” Chuck wrote last fall. “It is not. The normal course of human development is for successful cities to mature incrementally over time. When that occurs, they become financially resilient. To build Strong Towns, a community's emphasis needs to shift from creating growth quickly and easily to building value in a broad and incremental way.”

Of course, complex systems aren’t invulnerable. Flooding a complex system with resources can transform it into something merely complicated. This how Neil Johnson describes that process in his book Simply Complexity:

Why is competition for limited resources so important in real world systems? The answer is simple. In real-world situations where there is no competition, it matters little what decisions people actually make. In other words, if there is an over-supply of desirable resources, then it doesn’t matter very much what we decide to do since we will still have enough of everything we need, and more. In such situations, we could each go around acting in whatever way we wanted, either cleverly or stupidly, and yet still end up with an embarrassment of riches. Hence there is no need to learn from the past, or adapt. The need for feedback then becomes pretty meaningless since we are all getting what we want all the time. The end result is that the collection of objects in question will behave in a fairly simple way. In particular, the lack of dependence on any feedback or interactions between the objects will make the overall system non-complex.

An “over-supply of desirable resources” makes the overall system “non-complex.” Think billions of dollars in federal funds to build new roads we don’t need and actually make traffic congestion worse. Think the neighborhood that’s been starved of resources suddenly receiving a cataclysmic amount of it—what we call the “trickle or the fire hose.” Think massive amounts of new development used to pay for the old growth we can’t afford to maintain anymore. Think Calvin gulping that last glass of water:

Complicated: Puddle

Complex: Calvin

By Source (WP:NFCC#4), Fair use, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58522475

Allowing our cities to become complex again is foundational to the Strong Towns approach. It’s really the only way we can begin to grow more resilient and financially productive places. To better understand the complexity of our cities, here are a few resources to go deeper:

“Effective Quarantines and Strong Towns,” by Spencer Gardner

“It’s Time to Rethink How We Regulate City-Building,” by Chris Brewster

“Limiting Nutrients, or Why Things Change Very Little and then All At Once,” by Daniel Herriges

“What Can Hives and Barnacles Teach Us About Solving a Housing Crisis?” by Patrick Condon

John Pattison is the Community Builder for Strong Towns. In this role, he works with advocates in hundreds of communities as they start and lead local Strong Towns groups called Local Conversations. John is the author of two books, most recently Slow Church (IVP), which takes inspiration from Slow Food and the other Slow movements to help faith communities reimagine how they live life together in the neighborhood. He also co-hosts The Membership, a podcast inspired by the life and work of Wendell Berry, the Kentucky farmer, writer, and activist. John and his family live in Silverton, Oregon. You can connect with him on Twitter at @johnepattison.

Want to start a Local Conversation, or implement the Strong Towns approach in your community? Email John.