Can One-Ways be a Middle-Way for the Suburbs?

Mike Brown is a transportation engineer and sponsor of Strong Towns through his firm, Metro Analytics. Today, he's sharing a guest article as a follow-up to his recent essay suggesting that one-way streets might not be quite as dangerous and economically draining as so many people have argued—at least not in every town. Check out the previous articles in Strong Towns' ongoing conversation about one-way streets here.

While many downtowns are choosing to convert their one-way streets into two-ways in order to slow traffic, I'd like to look at a place where one-way couplets can actually have a powerful traffic calming effect and help avoid the proliferation of stroads: the suburbs, and particularly greenfield sites.

Replacing Would-Be Stroads With Town Center One-Ways

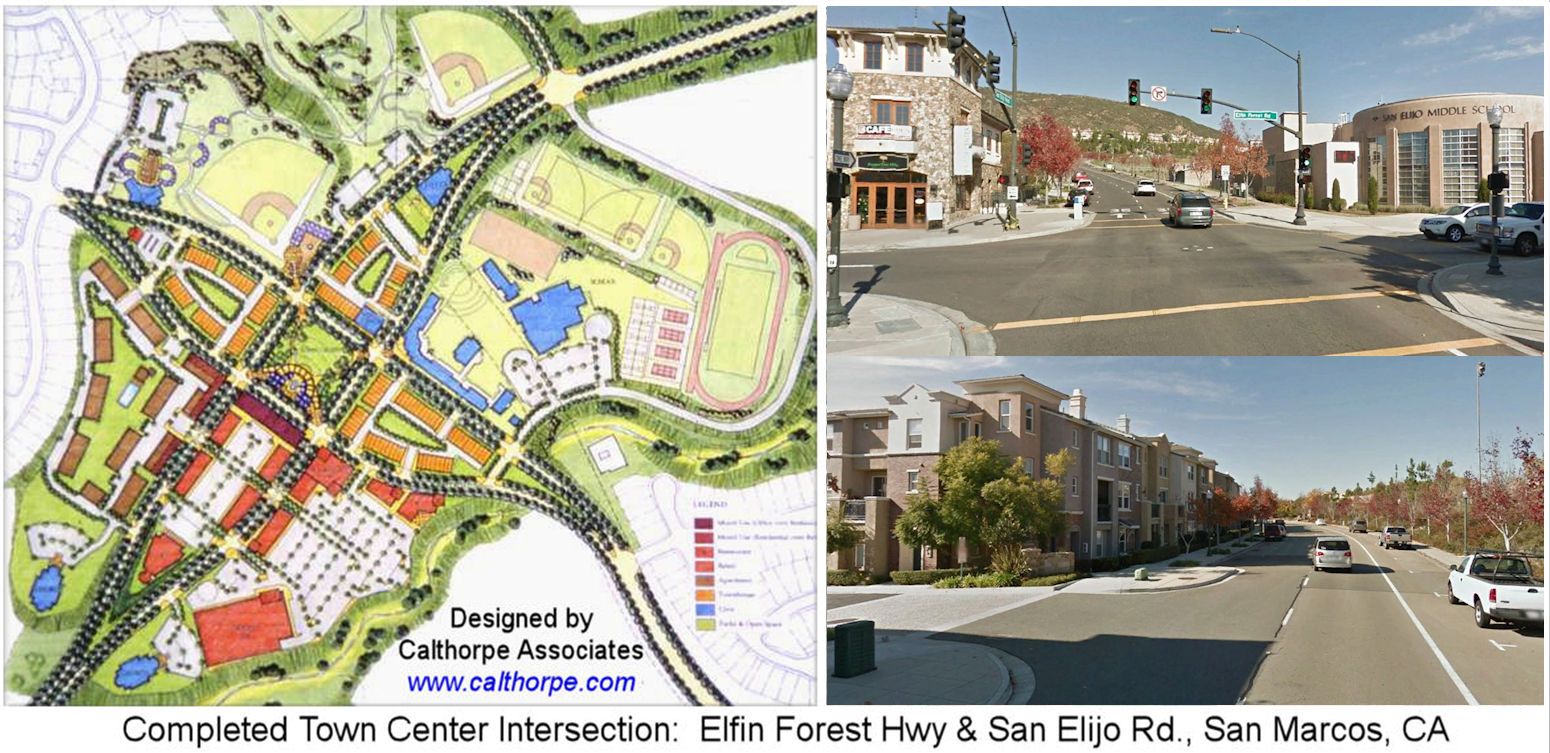

Nice pockets of walkable urbanism in each quadrant of a disastrously nasty double-left intersection would be a real shame. This is where one-ways can bridge the gap—fitting in with the engineer’s hierarchy and managing the reality of incoming stroads, in a way that is highly compatible with walkable development. Calthorpe Associates has many great examples. One of my favorites is in San Marcos, CA, near San Diego:

In this case, the two highways would have likely emerged as typical suburban 5-lane, 40-45 mph stroads with a single huge intersection. Calthorpe instead broke them into one-way pairs with four smaller intersections. The speed limit is just 25 mph, but peak-hour vehicles move through faster than they would have at 45 mph due to less congested intersections – an effect I call “drive slower, travel faster”. Below, I used the free StreetPlan.net to create these cross-section views of the above vs. the default stroads. The couplet intersections would need short left/right pockets to achieve higher throughput, but surely we can agree on which is better.

Here’s another Calthorpe town center in Issaquah Hills near Seattle. One-way couplets that are easy to cross encourage business growth and a walkable neighborhood feel, while a wide stroad would likely have resulted in far less development and a far more dangerous area for pedestrians and drivers alike.

Stroad vs. Couplet

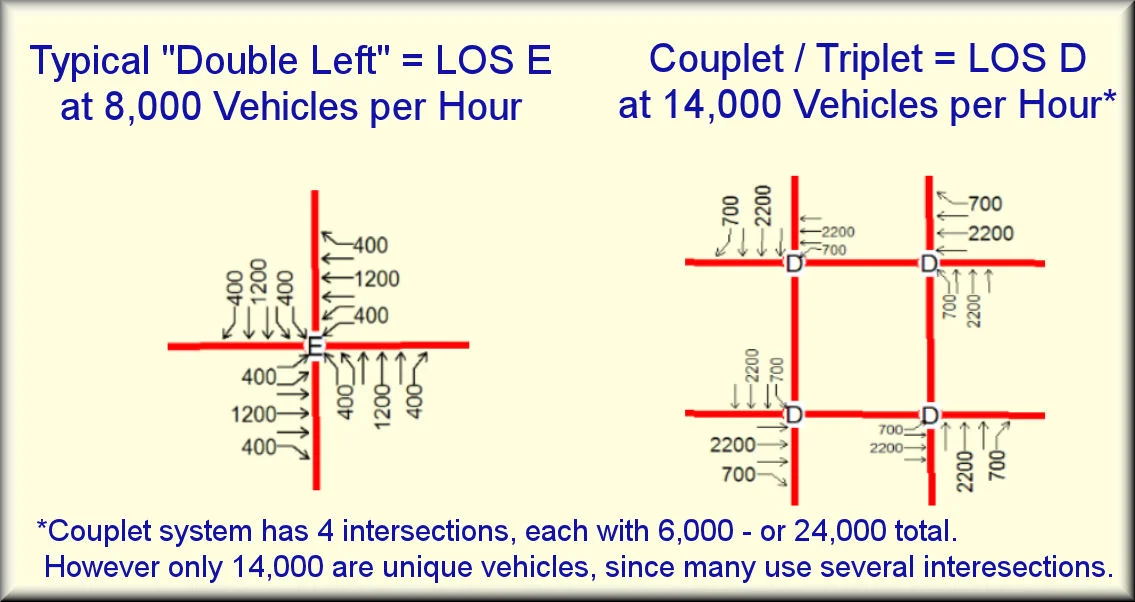

Below is a stroad vs. a couplet analyzed with Synchro, a common software used by traffic engineers. Both are equal in overall lanes (though the couplets have one less left-turn lane). The stroad system gums up at 8,000 vehicles per day (Level of Service E), while the couplet system, with smaller intersections and less overall pavement, serves 75% more traffic, or 14,000 unique vehicles per day with less congestion (LOS D).

How is “More Traffic” More Walkable?

So how exactly can the ability to support more vehicles be considered more walkable? If there is to be much walking and biking, then a lot of development must exist in a form that results in short trips. In a world so addicted to autos, most nodes outside large central business districts can’t encourage much business development if they hit an early ceiling on auto accessibility. And even if you “stroadify” for auto access, if resulting arterials aren’t livable, then only auto-oriented commercial will be built (poor mix = few short trips).

From this analysis, 75% more traffic capability will equate to much more than 75% additional development potential, because walking, biking, and transit will start to take much more of the load. This isn’t the only way to blend suburban stroads into New Urbanist greenfields, but it’s probably my favorite way.

For a larger activity center, “Triplets” may be a good option (see the graphic on the right). A triplet has a center alignment that is not necessary for traffic, so it can be whatever you want (perhaps most ideally access to on-street angle parking, regional transit stops, and bike/ped infrastructure).

Can We Shake Hands Instead of Wrestle for the Upper-Hand?

The engineer/architect relationship is kind of left-brain/right-brain. We’re supposed to work together to hit the same mark – beautiful, productive cities that function well for all modes. But for 60+ years left-brain (hare-brain?) engineers focused exclusively on function for cars, and created a mess of stroads and mega-freeways that don’t work very well, even for cars. The right-brain architectural/planning side is justifiably angry and reclaiming credibility. But engineers are still the 800-lb gorillas of the congested, dendritic hierarchy suburbs. Until we drastically change our road design system, we’ll probably need to listen to them and offer thoughtful ways to manage higher volumes of traffic within their hierarchy.

Even if you’re convinced one-ways are bad for historic downtowns – and I’m open to that – can they still be useful for curtailing would-be stroads? If a nasty two-way, 5-lane stroad is the alternative, then maybe some of the one-way examples I’ve offered are a good middle-way.

Help us engineers reinvent one-ways in a way that works well for all modes, and for hundreds of years of intensification. Then we can finally shake hands instead of wrestle for the upper-hand.

Related stories

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mike Brown is a transportation engineer who hopes to kill proposals for new stroads, and convert existing ones into walkable boulevards. He hopes to stop the “build-our-way-out with freeways” temptation by optimizing freeways instead, or downsizing those that just don’t make sense to continue. Mike founded Metro Analytics to pursue those objectives. Metro sponsors InnovativeIntersections.org, where you can discover cutting-edge Place-Making methods for managing high-volumes of traffic at low speeds, and catalyzing mixed-use development. Metro also sponsors StreetPlan.net, a free Complete Street cross-section development tool that follows ITE/CNU best practice guidelines. Mike is based in Salt Lake City, Utah.

When choosing between a narrow one-way couplet and a large stroad, one-ways get my vote every time.