Kick the Tires on Your Local Zoning Code

One of the great mysteries of my adult life has been trying to understand why nobody builds lovely places anymore. How hard can it be? Our ancestors built amazing cities with little more than horses, hand tools, and human muscle.

Who doesn't love old places? (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

But with all our modern knowledge and technology, we’ve built a lot of depressing stuff. Gargantuan shopping centers. Massive “garden” apartments. Multi-car garages that people live behind and call homes.

It wasn’t until recently that I started to understand how these developments were regulated into existence. Everything from federal housing policies and loan industry underwriting rules to local zoning codes have played a part.

It’s a shame that the era of mass-produced real estate corresponded with the era of auto-oriented regulation and design. Unfortunately, when these two Wonder Twin powers activated, they formed the shape of a lot of lousy places.

So I keep going back to older neighborhoods, looking for the good stuff and wondering how we can infuse great design into the modern world.

A graceful 4-plex apartment building fits nicely in any neighborhood. (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

Two of my favorites? The traditional 4-plex apartment building, and the old-fashioned residential-above-commercial building. Fortunately, these are exactly the types of buildings that small, independent developers can build, if only the zoning code would let them.

If you’ve been following the Incremental Development Alliance (and you should), you know that one of the primary rules of small-scale development is: “Avoid brain damage. Build by right.” This means that you don’t want to spend a lot of time and money haggling with the local Planning Commission or the Board of Adjustment. You want to find a place where you can build "by right," under existing zoning.

Unfortunately, if you’re trying to build human-scaled, walkable places, you’re likely to crash headfirst into the brick wall that is your local zoning code, especially if it hasn’t been updated in a while. Those 70’s-era land-use regulations heavily favor single-use zoning, arbitrary limits on density, and lots of parking. And we've already got plenty of that.

Since the City of Tulsa (where I live) recently updated its zoning ordinance, I thought it would be fun (nerd alert!) to test a hypothetical project against the code to see if it helps or hinders small-scale infill projects in our older neighborhoods.

As a test case, I’m using a lovely old 4-plex as a model, which I think fits nicely into a lot of different neighborhood contexts. (It also makes for a great place to live.) Next, I selected a typical lot in an older neighborhood near downtown that needs some love and reinvestment. My goal is to see if we could build this building by right in this area.

If this building's not allowed by right, there's something wrong with your zoning code. (Photo by Sarah Kobos)

If you’re interested in kicking the tires on your city’s zoning code to see how well it would support missing middle housing, give this exercise a try.

Step 1: Search for trace evidence of walkability.

Focus on older neighborhoods. Look for a compact, connected street grid and surviving remnants of human-scaled, commercial streets. These areas may have suffered decades of neglect thanks to destructive policies and regulations that incentivized investment on the fringes of the city. But they’ve got “good bones” and they’re full of potential for small-scale developers looking to make a difference.

Step 2: Find your city’s zoning map and figure out how these areas are zoned.

If you’re lucky, the zoning map is available online. Focus on the areas that interest you and see how they’re zoned. Take notes. It will all become clear soon.

For my four-plex test, I’m interested in an older part of town that has a lot of RM-2 (Residential Multi-Family, Medium Density) zoning, so I’ll focus on that.

Typical Zoning Map

Step 3: Crack open the zoning code.

Now that you’ve identified the zoning district(s) on a map, you can find the corresponding regulations in your city's zoning ordinance. Not all zoning codes are particularly logical or easy to navigate. Pour a strong coffee — or a stiff drink — and prepare to enter the Nerd Zone.

Step 4: Time to kick the tires!

Every zoning code is different, but these are some common concepts that you’ll probably need to consider.

Permitted Use

Use-based zoning ordinances (as opposed to “form-based” codes) include amusingly specific lists of “primary uses” allowed in each zoning district. Some codes may add an extra layer of confusion by categorizing uses into more general “use units.” Either way, you’re looking for a list or table specific to the zoning district(s) you identified on the map. This will show what you can build “by right,” what’s prohibited, and what requires a “special exception” within each district.

Since I’m testing out a traditional four-plex, it will qualify as a “Multi-Unit House,” which is basically a small apartment building with a single street-facing entrance. This is a new building type allowed by right in the RM-2 district that didn’t exist in the previous version of Tulsa’s zoning code. In the past, my small 4-plex would be confusingly classified both as an “apartment” and as a “multi-family development” in different sections of the code.

Next, move on to the pesky “Bulk and Area” requirements.

Minimum Lot Area

This determines the minimum amount of land required for various building types. It’s measured in square feet (SF) from the property lines.

My hypothetical 4-plex (aka: Multi-Unit House) in an RM-2 zoning district requires a minimum lot area of 5,500 SF. This is dandy because my test lot is 50 x 140 feet, or 7,000 SF.

Just a few of the bulk and area requirements you'll find in a zoning code.

Minimum Lot Area Per Unit

This requirement is another method cities use to regulate density, essentially limiting the number of housing units that can exist within a certain square footage of land. If you’re a small developer trying to imitate great old buildings, this requirement can really bite you in the butt. Look at the required square footage per unit and multiply it by the number of units you wish to build. The total can’t exceed the size of your lot.

Fortunately, in Tulsa’s updated zoning code, these numbers were reduced a bit to improve our chances of building something more productive. The requirement for a Multi-Unit House in an RM-2 district is 1,100 square feet per unit, which equals 4,400 square feet for my little 4-plex. Again, no problem because our lot is 7,000 SF.

Minimum Lot Width

This determines how wide your lot must be for various types of buildings. It’s measured between the side property lines of a lot. If your lot is a rectangle, this measurement is easy. If it’s an odd shape, you’ll need to calculate the average width of the lot.

For our test, the lot must be a minimum of 50-feet wide, which is exactly what we’ve got.

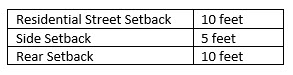

Minimum Building Setbacks

Building setbacks are typically measured from the property lot line to the nearest exterior building wall. In some cases, they may be measured from a different reference point, like the centerline of the street. You’ll want to look at front, rear, and side setbacks. There will probably be other setbacks for features like parking, detached garages, or screening walls, but don’t worry about that right now.

Our little Multi-Unit House in an RM-2 district has the following setback requirements:

If your zoning code requires “build-to” lines rather than setbacks, congratulate yourself for living in a place that understands the importance of building placement. This is one way to make sure buildings front the street with parking located in the rear, rather than vice-versa.

Minimum Open Space Per Unit

This is another standard that limits density. It’s the amount of outdoor “open space” required for each dwelling unit. Open space is further defined as “outdoor areas not occupied by buildings, driveways, or parking areas.” (Uh-oh…)

OK, so let’s take a look. Our Multi-Unit House requires 200 square feet of open space per unit. Since it’s a four-plex, we’ll need 800 square feet of land in addition to that required for the building, off-street parking, and driveways. (More on parking and driveways later.)

Maximum Building Height

This one’s pretty self-explanatory. The Maximum Building Height in our RM-2 district is 35 feet, which should be more than enough for our little two-story building. Be alert for additional restrictions on height that may be imposed if a particular lot is adjacent to a single-family residential zoning district.

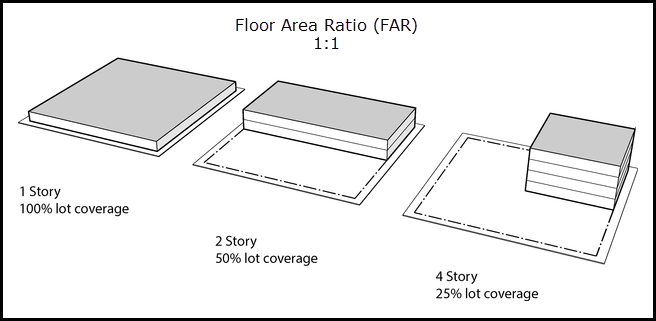

Floor Area Ratio (FAR)

The floor area ratio is the total floor area of a building divided by the area of the lot. Some codes exempt certain areas of the building (such as stairwells or mechanical rooms) from the calculation. It’s another one of those arbitrary limitations on density that I don’t understand, and it often impacts the ability to build two- and three-story buildings on a given site.

Example of Floor Area Ratio. Each of these buildings would have a FAR of 1.0. (Source: portlandoregon.gov)

The FAR doesn’t apply to our Multi-Unit House, but if it did, we would calculate it as: 3,196 SF (total square footage of both floors of our building) / 7,000 (total lot area) = .46 FAR.

Minimum Parking Requirements

This section of the zoning code is where great projects come to die, especially in traditional neighborhoods where the scale is not conducive to the needs of auto storage. There are a lot of extremely specific, pseudo-scientific methods used to calculate minimum parking requirements, which would be amusing if they weren't so devastating to cities.

Typically, parking requirements for residential buildings are based on the number of units and bedrooms, while commercial buildings require a certain number of spaces per square foot of building floor space. Requirements for mixed-use buildings combine both methods.

Parking requirements are super-specific, and totally arbitrary.

For our Multi-Unit House, the code requires 1.25 parking spaces per one-bedroom unit. Thus, 4 x 1.25 = 5 off-street parking spaces. Each parking stall must be a minimum of 8.5 feet x 18 feet with a 12-foot wide drive-aisle. So the minimum area dedicated to off-street parking is 1,275 square feet, not counting additional driveway access that may be needed to reach the parking lot.

Be sure to look for additional rules about setbacks and where parking is allowed. In our test case, for example, it’s not allowed between the building and the street; it can obstruct rear setbacks but not front or side setbacks.

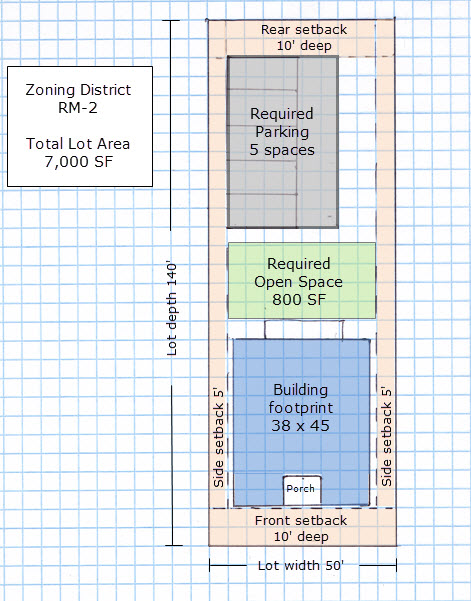

Step 5: Grab a pen and paper and start drawing.

The best way to see how all this stuff fits (or doesn’t fit) is to sketch it out on paper. Here’s my layman’s version of what we’ve described above. This quickly reveals both the possibilities and the limitations of our test case.

You may have already noticed the problem. If the lot doesn’t have alley access, it’s going to limit what we can do because we’re going to need a way to reach all that required parking behind the building. (And no, the solution is NOT to put the parking in front!)

Some older neighborhoods in Tulsa still have alleys, but it’s becoming more of an exception than a rule as we’ve chosen to abandon alleys rather than maintain them. (We’d rather widen stroads and maintain cul-de-sacs in car-centric places. Go figure.)

In our test scenario, a driveway is allowed in the side setback. So one option is to reduce the width of the building, which would provide space for a driveway along one side. I’m not an architect, so I can’t judge how much this would impact the livability of the apartment building. I assume it could still be fabulous. But it’s always a bummer when you have to compromise a human habitat in the name of auto-storage regulations.

Now, test out a couple scenarios of your own.

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve obviously got the nerdy patience and passion to test out your city’s zoning code. Find a little old building you admire that contributes to its surroundings and the local tax base. Next, pick an area of town that needs some love and reinvestment. Then see if your building could be built by right in that neighborhood, under current zoning. If not, it might be time for an update. Nerd powers activate! Good luck!

(Top photo source: J. Albert Bowden II)

Sarah Kobos has been a regular contributor for Strong Towns since 2016. She is an urban design nerd and community activist from Tulsa, OK. Her superpower is the ability to transform almost any topic into a conversation about zoning. Whenever possible, she explores other cities and writes about urban design and land use issues at AccidentalUrbanist.com.