Parking Dominates Our Cities. But Do We Really *See* It?

I'm gonna start this one out with a bold thesis: Parking is the dominant physical feature of the postwar American city.

Not homes. Not strip malls. Not streets, highways, or stroads. Parking. We have a lot of the stuff. A few superlatives can express the sheer amount:

There are somewhere between 800 million and 2 billion parking stalls in the United States.

There are between 3 and 8 stalls for every registered vehicle.

Surface parking lots alone cover more than 5% of all urban land in the United States.

That represents an area greater than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

In Los Angeles, parking occupies more land than housing.

Those big-picture statistics about parking's dominance of our landscape can be shocking in the abstract. And they can make for startling visual images, such as everything within the borders of two east coast states paved over:

Or the literal "parking crater" that would result if we took all 200 square miles of Los Angeles County parking and agglomerated it into one blast radius:

Image via Better Institutions blog

But these images, while shocking in their own way, don't actually tend to translate to the way people talk about parking in their neighborhoods and at the on-the-ground locations they visit on a regular basis. The scale is too big, so you expect big numbers and you become numb to how big they actually are, in the same way that people react blankly if you tell them what the national debt is, or what the U.S. spends on the military each year.

How many of us can really conceive of 2 billion as a number, let alone in a way that means anything to our lives?

And so we get to the really funny thing about parking, when you zoom in to the scale at which we actually live our lives, which is just how invisible it is.

Parking Has Eaten Our Cities. Have Most of Us Even Noticed?

Some of the things I talk about as an advocate are easy conversation starters: affordable housing, for instance. Everyone has paid rent or a mortgage. I don't have to preface that conversation by convincing anyone of the issue's importance; they get it.

"We require homes and businesses to have too much parking," though? Way tougher sell. A lot of people stare blankly at me. How could you have too much parking, after all? Sounds like a good problem to have, right? It's like having too much cranberry sauce on your Thanksgiving table: worst case, you just won't eat it all and there'll be some left over.

To understand why too much parking is a problem, you have to recognize how it dominates our environment and squeezes out other possibilities for how we could live and what we could create. But parking is kind of like The Silence from Doctor Who—a monster that has taken over every corner of your world, but as soon as you're not looking at it, you forget all about its existence.

I wrote in a recent post about how the human brain is wired to conceive of distance as a function of time. We habitually say things like "It's ten minutes away," rather than talking in terms of feet or miles. This mental process is why it's not an intuitively obvious fact that a Walmart parking lot is bigger than a Walmart store. When you drive to Walmart, you spend maybe 1 minute in the parking lot, whereas it takes longer than that just to walk from one end of the store to the other.

And yet it's true: a Walmart parking lot is, almost without fail, bigger than the store itself. The same goes for many commercial building types.

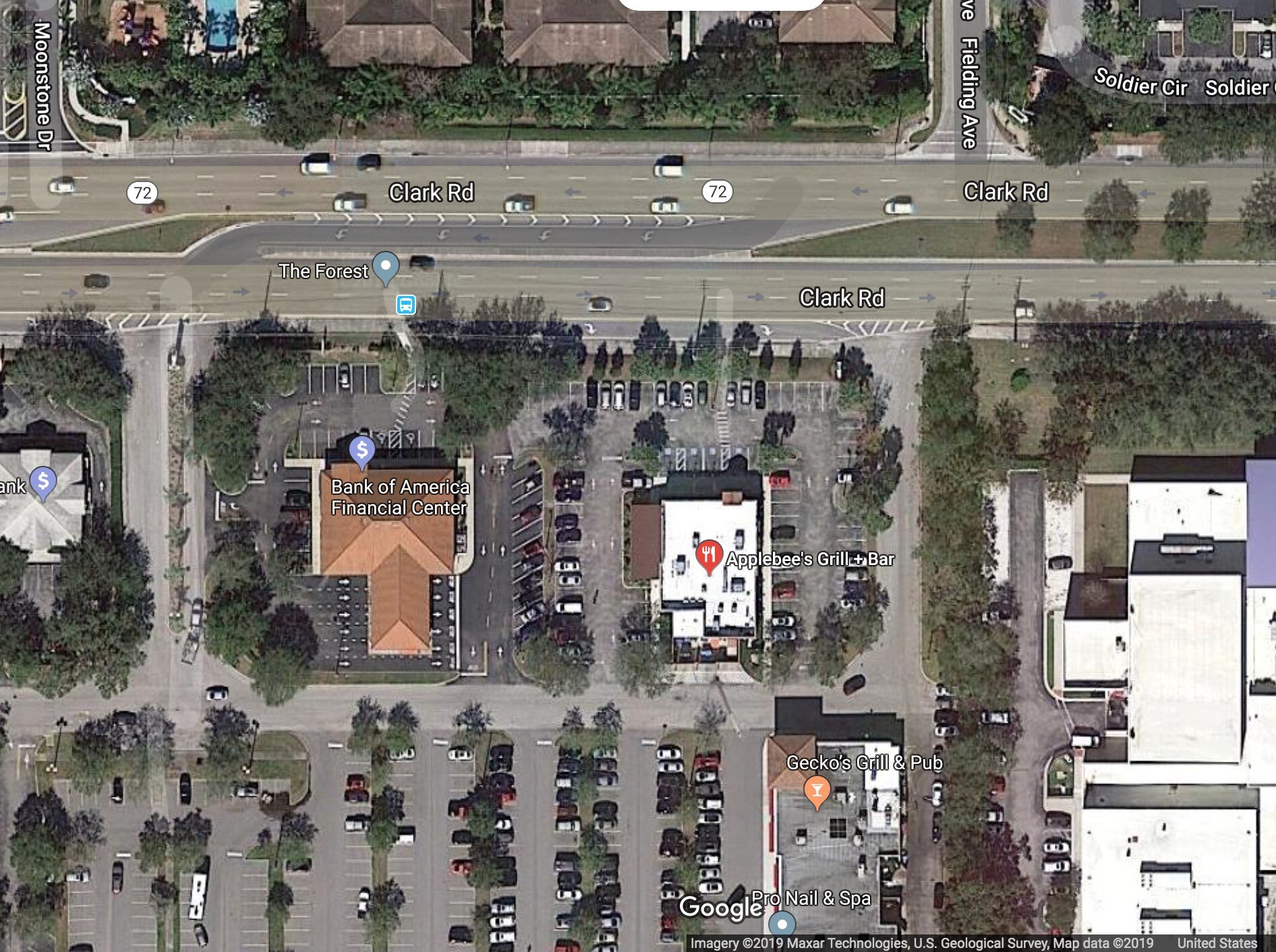

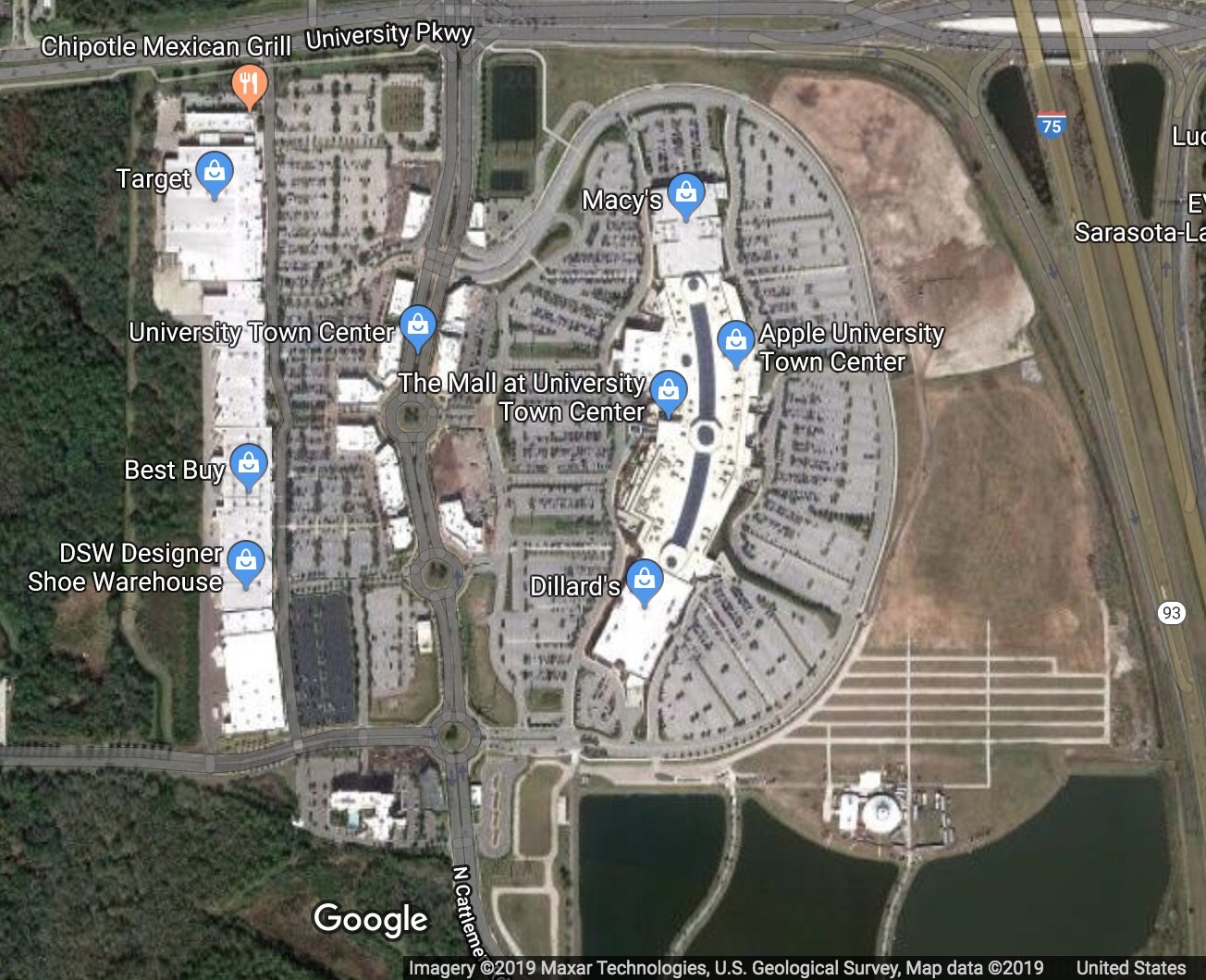

Parking has eaten our downtowns. A parking-versus-not-parking map suffices to show that in dramatic fashion. Here's Peoria, Illinois’s downtown, with all the parking highlighted in red:

Here’s Des Moines, Iowa:

Zoom in on a suburban commercial corridor in Des Moines, and it becomes plain as day that parking, not buildings, is the dominant feature of the landscape:

We don't experience the parking in any of these environments as being larger than the actual destination—by which I mean that it doesn't loom larger in our consciousness. But it is larger, and that has huge implications for our physical imprint on the earth and its consequences.

The United States has roughly 300 square meters of impervious (paved) surface per capita. That's about 3,200 square feet, or very close to the size of a standard Chicago residential lot, 25’ wide by 125’ deep. That’s a separate one of these for each member of your household, adult or child:

The Netherlands, on the other hand, has only 40% as much paved land per capita as the U.S. For Germany or Japan, the figure is closer to 1/3. You wouldn't know it from a look at their cities—far less green and lush than ours—but it turns out that a compact development pattern allows far more countryside to be preserved.

Building like this…

…leaves room for this.

All that parking in the far more car-dependent U.S. is not the only reason, but it's a huge reason why we've paved so much more of the earth.

All that parking is pavement that can't absorb stormwater, leading to flooding and pollution problems from runoff.

All that parking is pavement that absorbs heat from the sun and contributes to the deadly urban heat island effect.

All that parking is pavement that has to be maintained, kept smooth, cleared of snow and ice in the winter.

All that parking is pavement that sewer pipes, power lines, and internet cables must traverse to reach their destinations—with huge cost consequences.

All that parking is pavement that people must traverse to reach their destinations. (If you don’t see the problem with a downtown dotted with surface parking like Peoria’s above, try walking a few blocks in high wind, rain, or snow. You’ll notice the parking lots: they’re the windswept gaps.)

All that parking is pavement that generates no wealth for our cities—that is just an appendage to the places we actually love and care about.

All that parking is lost potential.

Parking Is the Number One Constraint on Our Cities

The actual impact of parking on urban form is far greater than even the amount of land occupied by the parking itself. This is because the requirement to provide parking tends to dictate almost everything else about how we design places, right down to where a building is situated on its lot, how big it is, and where to put the main entrance. This is the real reason why I called it the dominant physical feature of our cities.

Want to open a small retail store? According to a very common parking standard found on literally thousands of cities’ books, you may need to provide one off-street parking stall per 500 sq. ft. of floor area. Here’s the most cramped way imaginable to visualize this:

The reality is even worse than what this diagram depicts, because this just includes the actual parking spaces. But where are you going to put that parking lot? In front of the building? You’ll need a curb cut to get in, and room for a sidewalk and maybe landscaping or a guard rail. If you have more than one row of parking, you’ll need a sufficient drive aisle. Put the parking behind the building? Either you have alley access, or you need a driveway along the side of the building, narrowing the space it can take up.

Buy the adjacent building and tear it down? That’s a common solution, resulting in a “gap-toothed” urban fabric, like in this photo from Pocatello, Idaho. Benjamin Ledford explains how the city’s parking requirements lead directly to this sort of outcome: preserving one good building requires demolishing one or two others in order to make room for enough parking.

Instead of a continuous wall of buildings, these parking “gaps” (which make strolling less pleasant, safe, and convenient) have come to characterize many urban commercial streets and small-town downtowns. (Image via Google)

Parking requirements might be the reason you can't build a triplex or a backyard mother-in-law cottage. They might be the reason you can't renovate a historic building in your downtown. In fact, parking requirements would render the vast majority of historic "main street" districts in America's small towns and urban neighborhoods illegal to replicate today.

Want more in-depth examples of how parking can make it impossible to build a compatible building on a small urban lot?

An extreme case of a “parking podium” building. (Source: Eric Allix Rogers via Flickr)

Parking’s sometimes invisible imprint looms large nearly everywhere you go. It is the reason for “snout houses,” those much-loathed suburban homes that look like a garage with a house attached. Parking dictates design in high-rise districts too, resulting in podium buildings and Texas doughnuts. My otherwise very suburban, low-rise city has a high-rise downtown full of 10-story condos. And yet surprisingly, downtown is not the most densely-populated neighborhood; a trailer park a few miles away takes that honor. How is it possible that a trailer park is denser than a cluster of 10-story buildings? You guessed it: a huge share of the space in those high-rises is actually devoted to parking, not living.

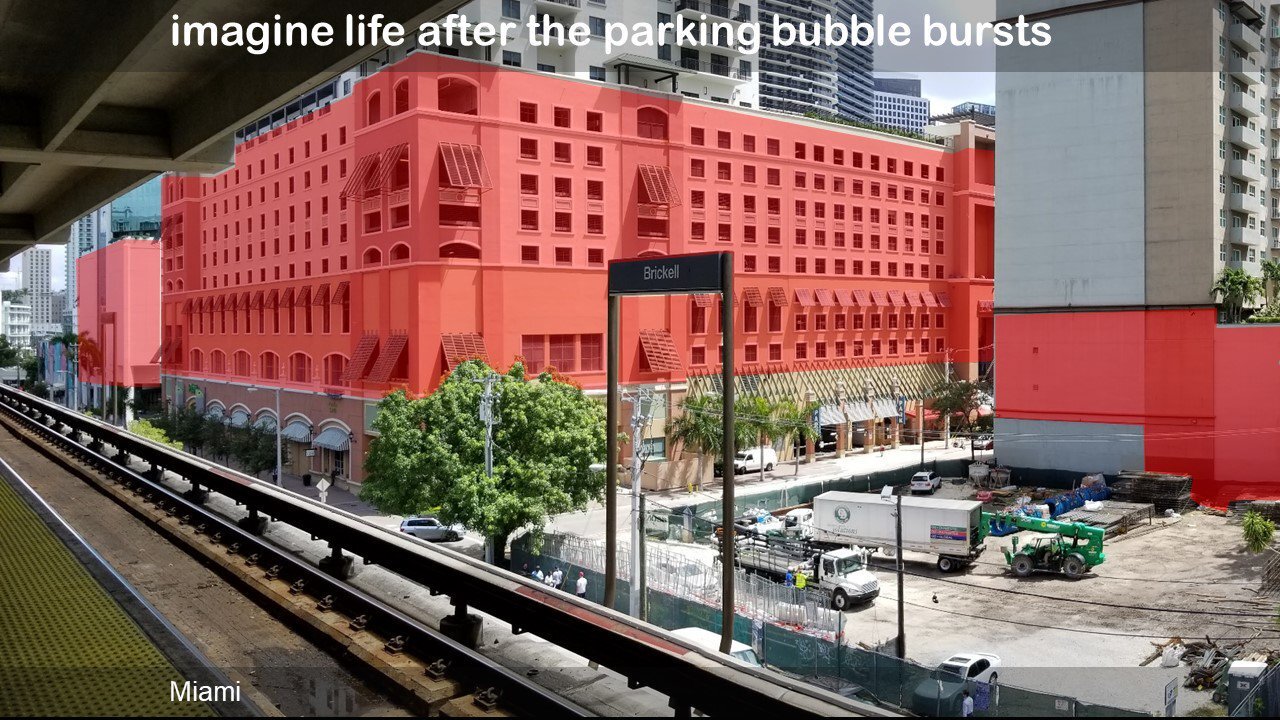

Victor Dover, of the renowned design firm Dover Kohl, tweeted these photos of U.S. downtowns during our 2018 #BlackFridayParking challenge, using a color overlay to show us, in a striking way, the opportunity cost of building too much parking. Let your imagination run wild: what else could those shaded areas be? (Click each image to view it full-sized.)

Scratch a bit at nearly any objection to infill development, and you hit the issue of making room for cars. Development opponents at public meetings often claim that their cities are full; that they are overcrowded, even. Yet no city in North America is even close to overcrowded with humans. (Very few cities on the planet are.) By and large, we don't spend our days in cramped spaces, jostling for room on the sidewalk or a bit of free grass to lounge on in the park.

Many cities in North America are arguably overcrowded with cars. And so, as Donald Shoup observes, parking becomes the reason many of our fellow citizens will fight the growth of their neighborhoods tooth and nail:

There's an old joke that if aliens landed in North America, they'd think that cars were the dominant life form on Earth—a metallic exoskeleton housing a squishy little brain inside. I'm not so sure it's a joke.

Back to Sanity

As long as we have cars, we will need to park them. But our perceived need for parking has been vastly inflated, for several reasons.

Separation of different land uses from each other means that few trips can be made within walking distance, and so we now need a separate parking space everywhere we go: home, the office, the gym, the grocery store, a place of worship, etc. In a walkable, mixed-use neighborhood, it’s much easier to park the car once and then make multiple stops on foot—no longer necessitating that each business have a parking space for every potential customer.

Parking minimums, as we’ve discussed before, are also geared toward maximum demand—like on the peak shopping day of Black Friday—and they tend to be overestimates even for those occasions. Every city should do away with mandatory parking minimums and let the market figure out how much parking we really need.

Want to help your neighbors see all that parking in your city in a new light? Start by grabbing your camera on Black Friday and shooting some photos of empty or largely-empty retail parking lots, and then posting them to social media with hashtag #BlackFridayParking.

Daniel Herriges has been a regular contributor to Strong Towns since 2015 and is also a founding member of the organization. His work at Strong Towns focuses on housing issues, small-scale and incremental development, urban design, and lowering the barriers to entry for people to participate in creating resilient and prosperous neighborhoods. Daniel has a Masters in Urban and Regional Planning from the University of Minnesota, with a concentration in Housing and Community Development.

Daniel’s work with Strong Towns reflects a lifelong fascination with cities and how they work. When he’s not perusing maps (for work or pleasure), he can be found exploring out-of-the-way neighborhoods on foot or bicycle. Daniel has lived in Northern California and Southwest Florida, and he now resides back in his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, along with his wife and two children.