Boston's Costly Missed Opportunities

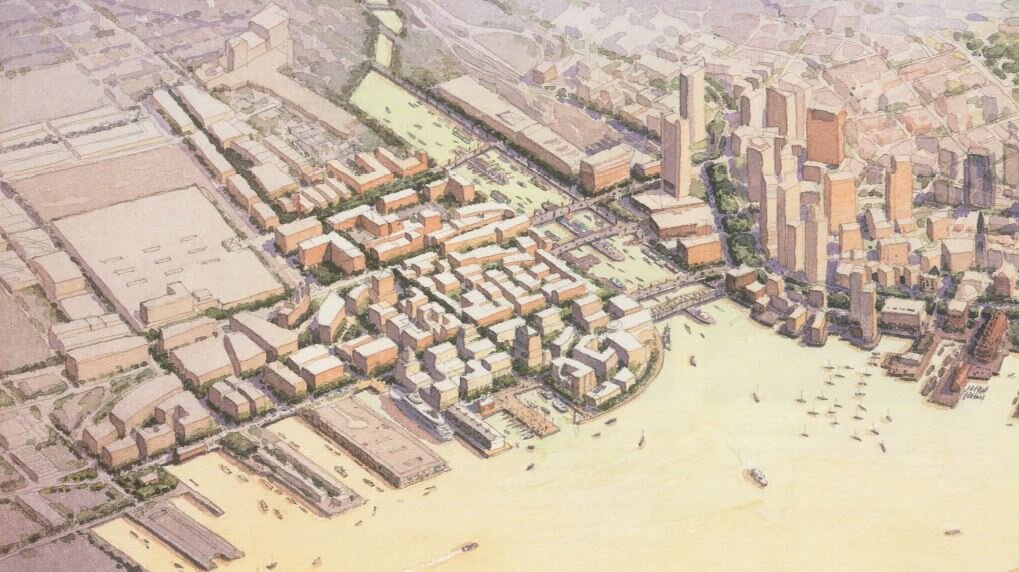

Boston’ Seaport, November 2019. Image credit.

Boston is one of the most successful American cities of the past two decades, growing in population and wealth and undergoing a physical transformation officials sometimes tout as the city’s “third building boom” (following its nineteenth-century growth and the urban renewal of the 1960s). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Boston was on track to surpass its 1950 population peak of around 800,000 by 2030—and major housing projects continue to be proposed and move forward in the planning process, so it may yet reach that level.

One of the most dramatic transformations has been the Seaport. In the 1990s it was a series of parking lots and decaying piers, with a few maritime industries left, such as fishing and seafood processing. Over the past 20 years, it has become an active, mixed-use area of new glass towers, renovated industrial spaces, a new federal courthouse, a new convention center and hotels.

But the Seaport has been criticized for its inhuman scale, lack of civic spaces, poor transportation and connections to the rest of Boston, and lack of affordable housing.

In East Boston, at the old Suffolk Downs racetrack, another new neighborhood is being planned. The109-acre site—the last major individual land parcel—had the track itself, a grandstand, stables and a parking lot. In addition, it was served by two stops on the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s Blue Line: the eponymous Suffolk Downs and Beachmont. East Boston has historically been a working class neighborhood and many streets are lined with Boston’s traditional triple deckers, as well as denser tenement buildings. Once known for its shipyards that built some of the fastest clipper ships ever to sail, today its main feature is Boston’s Logan International Airport.

Owned by the developer HYM Investment Group, they have proposed to build a bunch of towers in a park, with modern glass curtain walls, no street grid and too much parking. In addition, 1,430 units of affordable housing will be created, while 40 acres will be left as “green space.” Renderings show boxy, separated buildings on individual blocks.

Despite the project’s literature committing to concepts like fine-grained, walkable urbanism, it’s clear from the design that this is just spin. The large roads, single block buildings and 6,760 parking spaces all suggest a design for cars no amount of green roofs can compensate for.

“An Elegant Scheme”

But it wasn’t always like this. Back in 1999, a plan was proposed for the Seaport that would be radical now in its commitment to authentic urbanism. Developed by Cooper, Robertson and Partners for the Boston Redevelopment Authority (now the Boston Planning and Development Authority), who had planned Battery Park City and Celebration, Florida. More recently the firm has done master plans for Drury University, Longwood University and Zuccotti Park in Manhattan. Partner Jacquelin Robertson, who died this past May, won the Driehaus Prize in 2007.

The Cooper, Robertson Plan was so innovative in its approach to New Urbanism that it was praised by James Howard Kunstler in his book The City in the Mind:

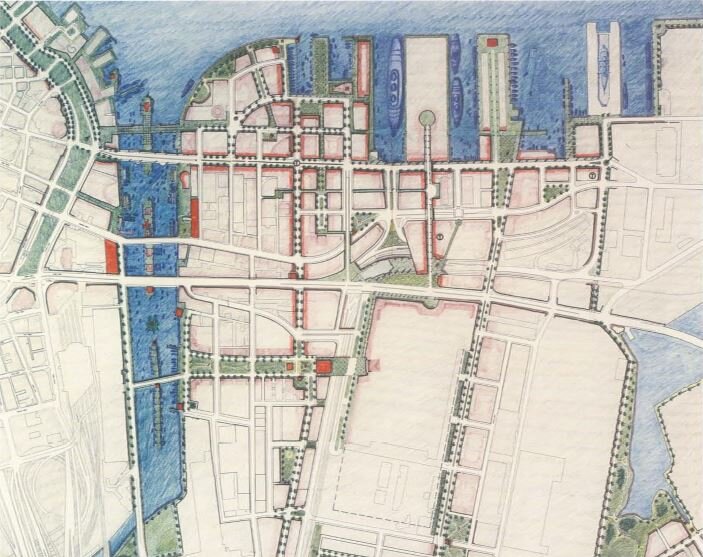

The “concept” plan they came up with for the Boston Seaport district was an elegant scheme of several small, distinct neighborhoods, small-scale blocks, intimate streets, dramatic vistas to the harbor and a rich network of small parks, waterside esplanades and tree-shaded avenues, creating a physical armature for all the mixed-use goodies off the BRA’s wish list. Buildings would be based on existing Boston typologies, with a 150-foot height restriction, and sloped back from the water to avoid the obstruction of vistas . . .

A rendering from Boston's 1999 Seaport Public Realm plan shows "what could have been", had the plan not been discarded under political pressure. It shows a more traditional, fine-grained approach to urban planning than the whole block or whole neighborhood projects Boston (and other cities) have been doing instead.

But the Cooper, Robertson Plan was never implemented, despite the investment of $20 billion by the city, state and federal governments. A new tunnel under Boston Harbor, now named for Red Sox great Ted Williams, was built and the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MPBTA) was planning a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) system, the Silver Line. A busway was built beneath Seaport Boulevard from South Station; plans included service to South Boston, the use of a disused portion of the Park Street tunnel, and dedicated bus lanes. The MBTA was also planning a circumferential BRT line called the Urban Ring. None of these transit projects were fully implemented and the Seaport remains lacking in transit.

Unfortunately, transportation was one of the weaker parts of the plan. In addition to Silver Line and Urban Ring, the plan advocated for water taxis and ferries to serve the waterfront. But while committed to pedestrian-friendly neighborhoods and active street fronts, it had little to suggest on how to keep truck traffic separate from that of pedestrians, other than recommending that it do so.

They also advocated breaking up the larger blocks of the Seaport many smaller streets, creating multiple approaches to the water, as well as more human-scaled environment and replicating the irregular block sizes of a traditional Boston neighborhood. As Kunstler remarked, instead of generic “green space” the plan called for a network of parks throughout the area, inspired by, but not copying, successful Boston parks like the Commonwealth Avenue Mall and other parts of Frederick Law Olmsted’s Emerald Necklace. In addition to its small neighborhood parks, the plan included a greenway route for bicycles and pedestrians from the Seaport to the Southwest Corridor, while the Harborwalk would have been expanded greatly to surround the whole district, with the idea that people would want to watch activities in the Marine Industrial Park.

Cooper, Robertson's 1999 proposal offered smaller blocks and streets for Boston's Seaport -- very different from the huge roads and superblocks that continue to make up the area.

The 1999 plan did not neglect parks, opting for many small examples, linked by greenways modeled on, but not imitating, the Commonwealth Avenue Mall. Few parks were actually built, however, and much of the Seaport continues to resemble an asphalt desert.

The Boston Convention Center, a huge building in the middle of nowhere over 1,500 feet long and 750 feet wide, would have also been different. Instead of a single main entrance on Summer Street and presenting mostly blank and monumental walls along its vast length, set back from D Street by the Lawn on D, Cooper, Robertson proposed making D Street the location of the main entrance. This put the center right on the street, creating an active wall with numerous restaurant, retail and other uses with separate entrances along the street. This would have greatly livened up an area that has remained rather dull and dead.

Because of the neighborhood’s past as a busy cargo terminal where goods could be transferred from ship to freight train or vice versa, Summer Street was built as an elevated street to reduce the number of at-grade crossings. Therefore, within the Seaport there are ramps connecting it to the ground level streets. The Cooper, Robertson plan proposed building along them to make them more pedestrian-friendly.

Costly Missed Opportunities

According to Kunstler, the plan was derailed by political interests in South Boston, which have historically been hostile to new housing, transit and other elements of the 21st-century city. However, the Urban Ring and parts of the Silver Line were also cancelled by the state smarting from the high costs of the Big Dig and a slow down in the Massachusetts economy. Other issues involved the Northern Avenue bridge, an historic landmark in the Fort Point Channel linking the Seaport to South Station and the Financial District; due to disrepair and disagreements between the city, state, and federal government, as well as other stakeholders, it has been permanently closed while it continues to decay.

“What [politicians from South Boston] surely feared as much as the loss of their elected positions was the very survival of Southie itself, and in that respect they were no doubt correct in their apprehensions,” Kunstler wrote. “If four or five new neighborhoods were successfully developed in the Seaport district, then it was logical to infer that adjoining Southie would be the next target of a yuppie invasion…In short, they feared the specter of gentrification.”

This rendering is perhaps the most hard-hitting for any Bostonian. From a vantage point on Dorchester Avenue across Fort Point Channel from the Seaport, it shows a never-built bridge, a never-built dock and a never-built linear park looking towards Wormwood Street. Today, that part of Dorchester Avenue is still truck parking for the United States Postal Service, while the vista would encompass little more than a parking lot with more trucks in the distance and the blank walls of the back of the Convention Center.

With the passage of some 20 years since that passage was written, we know that trying to prevent gentrification by not building anything, especially housing, is like trying to save someone from drowning by pouring water down their throat. The few hundred housing units that have been built in the Seaport have not prevented South Boston from becoming a neighborhood of cafés, wine bars, and Millennial professionals working in tech or services. It hasn’t even lost its old residents—they just made out like bandits on the real estate windfall. But the lack of transit service has greatly inhibited the neighborhood by keeping people in cars, making parking spaces a valuable—and even fought over—commodity.

Suffolk Downs—or Dorchester Bay City, a newly announced development that looks exactly the same as Suffolk Downs, but in a different part of the city—may have better public transportation options than the Seaport, being on the Blue and Red Lines respectively. But the failure of Boston planners to reestablish its traditional patterns of building and development have left the city poorer, both aesthetically and as a place to live.

About the Author

Matthew M. Robare is a Boston-based freelance writer specializing in urbanism and transportation. Follow him on Twitter @MattRobare. His website is www.mattrobarewrites.com.