The Difference Between Mobility and Accessibility

When I'm introducing people to the Strong Towns movement, one of the surest ways I've found to elicit a "Wait, what?!" is to start talking about slowing down traffic. #SlowTheCars is one of our rallying cries, not only for public safety reasons (starting with the tens of thousands of Americans killed by drivers every year), but because slow streets are more financially productive streets. They're places where we, as a community, can linger and interact with each other, and they’re platforms for creating real value.

Our take on traffic defies mainstream assumptions, to say the least. Everyone thinks they have a traffic problem, a belief fed by endless recycled headlines and pseudo-academic findings about the hours of productive time we supposedly lose to congestion. Yet numerous writers have argued in this space—convincingly, I hope—that congestion is, a) not something we can or should solve by building wider, faster roads through cities, and b) often not a problem at all. In fact it might even be a good thing.

I was informed recently by a local activist in the city I live in now that I espouse a "dangerous ideology of overcrowding our roads to force people to walk." This is not true. I'm not interested in being in the business of forcing anyone to do anything. But it is true that if we implemented the policies I want, many of us would get around our cities more slowly than we do now.

Here's why I'm not convinced that's a bad thing—or even an inconvenience.

Speed is the Wrong Metric

In the ways we talk about traffic congestion, we're too often obsessed with speed. Traffic analytics firm Inrix publishes its annual Congestion Index, the premises of which our friends at City Observatory and others have debunked repeatedly (and sometimes humorously). The annual Inrix report is full of alarmist data points devoid of any useful context. Its list of the worst cities for traffic reads like a “Who’s Who” of prosperous, economically dynamic places. But did you know that in Manhattan, you can travel only a measly 8.23 miles per hour on average?

Even mass transit projects are often assailed for their slowness. My hometown has a wildly successful light rail line that opened in 2014. The Green Line connects downtown St. Paul to downtown Minneapolis by way of the University of Minnesota and various neighborhoods. During its planning process, much of the public debate was about its speed. We were repeatedly told that the travel time from end to end was unacceptably long, that no one would ride it because driving was so much faster, and that we should have built a rapid rail connection down the middle of the freeway between the two cities instead, so that you could get from one end to the other faster.

The Green Line, nonetheless, has blown ridership projections out of the water, reaching its 2030 target thirteen years ahead of schedule. Its success is an object lesson in a crucial insight: that speed is entirely the wrong measure of the utility of transportation. To fixate on travel speed is to mistake mobility for accessibility.

The difference between the two concepts is simple:

Mobility is how far you can go in a given amount of time. Accessibility is how much you can get to in that time.

A pair of extreme examples illustrates the difference nicely. Rural Wyoming? Fabulous mobility—you have a high likelihood of unimpeded 70 mile-per-hour travel whenever you want. But accessibility is less impressive, because the places you might want to be in Wyoming are, as a rule, quite far from each other.

Midtown Manhattan? Mobility is rock bottom: driving is often slower than walking. but you have unparalleled accessibility—there's more of the world at your fingertips within 30 minutes than nearly anywhere else in, well, the world.

The point of travel isn't to cover ground: it's to get us to the things we want to do. It's to get us to our jobs, our friends and families, recreation, and daily needs. Accessibility, not mobility, is what matters.

And almost universally, the most accessibility-rich locations in the U.S. are places where you don't move very fast.

The Most Productive Places Are The Most Congested And The Most Access-Rich

The EPA maintains a Smart Location Database which provides some good measures of accessibility. Based on a combination of Census and land-use data, the database quantifies, for every census block group (block groups average roughly 1,500 inhabitants, and are generally a subset of a neighborhood), measures such as housing density, diversity of land use, some aspects of neighborhood design, and destination accessibility via car and transit, among others.

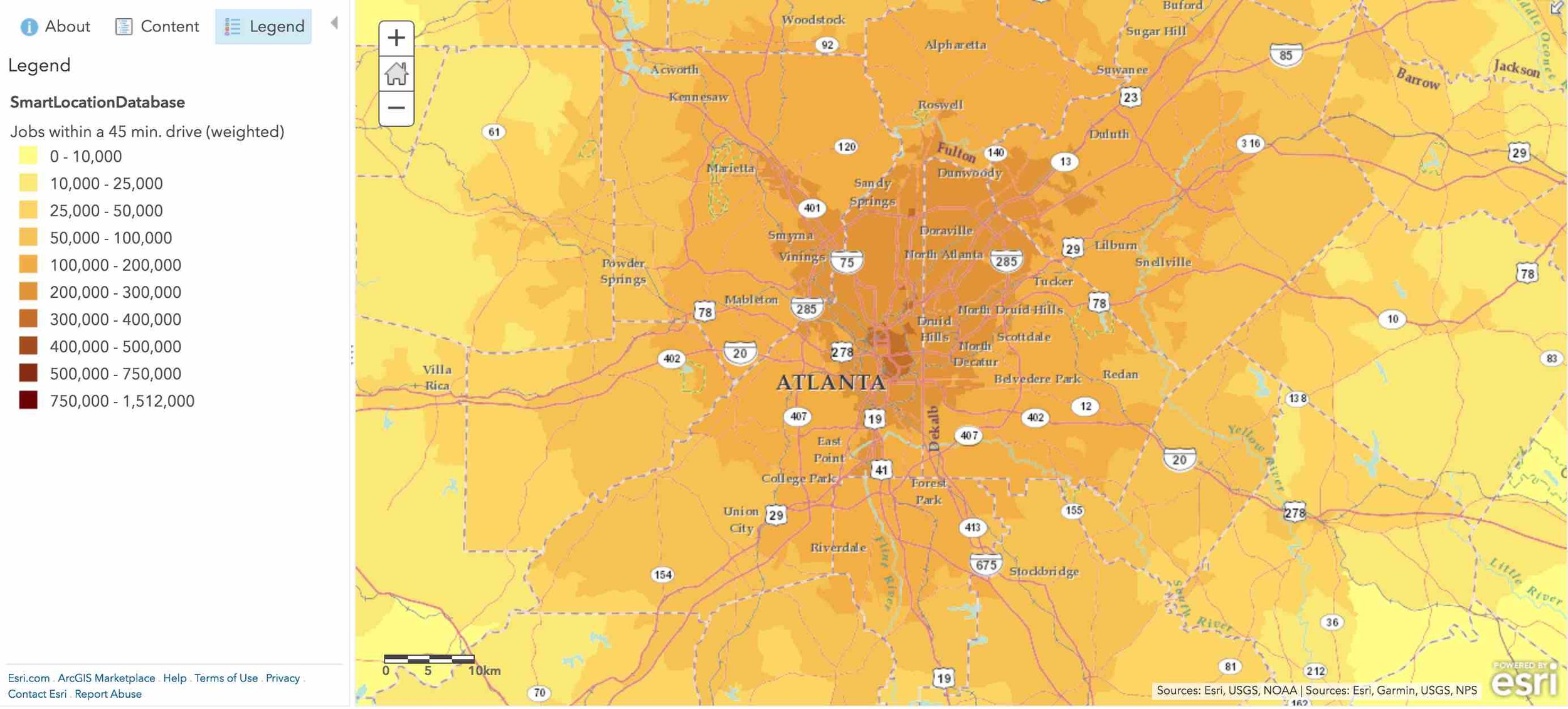

You can map these attributes online. Let's look at what the Smart Location Database has to say about access to jobs within a 45 minute transit trip from different parts of the top four cities on Inrix’s “most congested” list from last year. Look at where the darkest brown is on these maps—in the downtown core of each city (click the maps to view them full size, with a legend):

Okay, you say, but that's transit. Of course the downtown core fares well; transit networks are always centered there, while transit is scarce to nonexistent in suburbia. Surely if you look at accessibility by car, the pattern will reverse itself, because we all know driving downtown is miserable, right?

Here are some maps of the relative 45 minute job accessibility by car for the same four cities (again, click on the maps to see the legend):

You can drive to more jobs in 45 minutes from the crowded, congested centers of these cities, where driving conditions are supposedly miserable, than from nearly anywhere in their suburbs. The reason for this is simple: the centers are also where the biggest concentrations of jobs are. You're not going to drive very fast. But you're also not likely to have to drive very far.

What if We Measure Our Travel by Access, Not Speed?

Thinking about the purpose of travel as access, not travel for its own sake, allows us to put observations about slow travel speeds in better context. Let's revisit the Minneapolis-St. Paul Green Line I mentioned. I use this example because it's a transit line I'm extremely familiar with, because its travel speed varies dramatically along the route and has been a point of controversy, and because there's really good data available on what, exactly, exists along that route.

A map of the Green Line with the station walksheds color-coded by “Total Activity.”

Specifically, the Metropolitan Council, which oversees transit in the Twin Cities region, maintains a data set of the numbers of residents, workers, and post-secondary students within walking distance of each Green Line station. The sum of those three numbers is a "Total Activity" number that provides a very rough measure of how much interesting stuff is near each station.

I was able to combine that data with approximations of the line's travel speed between each pair of consecutive stations on a westbound journey. I used real-time travel data from two recent end-to-end Green Line runs, and averaged those times with the time the official schedule allots between stations to come up with an estimate of typical travel time from each station to the next. (Union Depot, the first station on the line, is omitted.) The graph looks like this:

Data: Metropolitan Council

As you can see, the train moves most slowly through downtown St. Paul, the University of Minnesota campus, and downtown Minneapolis. It travels relatively quickly through the St. Paul neighborhoods along the middle of the route.

But now let's reframe the trip in terms of how much activity—other people you might be traveling to meet, or buy something from, or sell or teach something to, etc.—you're gaining access to as you reach each station:

Data: Metropolitan Council

Here, the pattern almost completely reverses itself. The slow portions of the journey, in terms of miles of ground covered per unit time, are precisely the most efficient parts in terms of getting you to actual destinations. You know, the part you care about.

“Make it Easier to Get to the Stuff”

Strong Towns advocates for slow traffic, narrow streets, and for cities to not worry too much about congestion, yes. But we also advocate for the traditional development pattern: compact, pedestrian-oriented, and mixed-use. Building cities in this way is time-tested. It's financially sound. And it optimizes for the truly important measure of an effective transportation system: accessibility, not mobility.

Land-use and transportation professionals are rapidly coming around to this vision. Minneapolis city planner Paul Mogush has recently been on record explaining a key objective of the city's proposed comprehensive plan update with this memorable phrasing:

“Put the stuff closer together so it’s easier to get to the stuff.”

Sounds a lot like Strong Towns President Chuck Marohn in this article:

"Instead of building lanes, we need to be building corner stores.... For nearly seven decades, our national transportation obsession has been about maximizing the amount that you can drive. We now need to focus on minimizing the amount you are forced to drive.”

That vision—accessibility, not mobility—is what a transportation program for a strong city or town looks like.

(Cover photo via Metro Transit)

Don’t underestimate the power of small-scale development—if undertaken at a large scale, by many hands—to transform our cities for the better.