What Housing Vouchers Can And Can't Do

The headlines about (Your Place Name Here)'s housing affordability crisis are numbing these days. It doesn't seem to matter where you live: Nationwide, only 21 units affordable to extremely low-income renter households are available per 100 such households, and every county has a shortfall. Last year, eleven million low income households paid more than half their income in rent, a 20% increase since 2007.

There's a lot of interesting debate out there about whether this problem is actually new or getting worse, but it's certainly true that we're in a moment of widespread recognition of just how many Americans struggle to afford a place to live at all — let alone one in a safe neighborhood with access to good jobs. Wharton economist Todd Sinai has an interesting explanation for this recognition: While very low-income Americans have struggled to afford housing for decades, it is only recently that these affordability problems have crept up to also affect the middle class, especially in wealthy cities.

This crisis atmosphere has sparked a resurgence of interest in an aggressive, direct role for government in the housing market. The notion that government can and should directly subsidize housing on a massive scale, which had steadily fallen out of vogue for decades, is back with a vengeance.

When "Market Rate" is no Longer Affordable for Much of the Market

In extremely expensive places like coastal California, the term "market rate" as applied to a new home has become an epithet for many housing activists. New-construction homes in San Francisco are currently unaffordable to all but a small, wealthy sliver of that city's population. Some of the most radical calls for massive, transformative social housing programs, unsurprisingly, can be heard shouted from the city by the bay.

Even in places where "market rate" hasn't become synonymous with "for the one percent," new buildings are hardly ever affordable to the working class. The cost of construction alone tends to preclude it. Developers borrow money to finance construction, and must be able to repay the debt out of the rents coming in once the building is occupied. This puts a surprisingly high floor on how low those rents can go. The Urban Institute has a great interactive tool which lets you play with various assumptions and simulate the cost of building affordable housing.

There's a common misconception that if developers would just settle for a little less profit, they could build working-class housing without subsidy. This is almost never true. The reality is that, much as lower-income people usually buy used cars, lower-income people usually do not live in newly-constructed homes. This was true in 1920, it was true in 1950, it was true in 1980, and it is true today. The primary source of affordable housing is older housing that has "filtered" down from a higher price point.

The difference today is that in much of America — especially wealthy coastal America — even the middle class can no longer afford a new market-rate home or apartment. Over at Shelterforce, Rick Jacobus extends the car analogy to make this point: the problem isn't that we're building new Lexus housing, it's that we no longer build very much Ford Focus or Toyota Camry housing at all.

The middle classes find ways to make it work. They sacrifice location or amenities or square footage, they double up with roommates, they live with their parents for longer in their twenties, but they make it work.

The poor aren't so lucky. Many of them just leave wealthy places like California (which offer the greatest upward mobility) for places with cheap housing but less economic opportunity. Others lose out because they're deterred in the first place from moving to cities that are prospering. This stratification between "have" and "have not" regions of the United States — the dramatic decline in the ability of Americans of limited means to move to opportunity — is one of the most troubling economic and demographic stories of our time, and it has everything to do with housing costs.

It's essential that we tackle the long-term causes of this problem. But the market-based solutions out there — reduce regulatory barriers, allow more incremental development in more places — are long-term solutions. Filtering of housing down to a lower price point is a process that takes decades. Those at risk of displacement understandably want to know how they will get homes they can afford not in five years, not in ten, but right now.

Hence the widespread interest in dramatically expanding the scope of housing subsidies. So let's talk about one way this might be achieved, and what some of the implications are.

4 Forms of Government Housing Subsidy

To vastly simplify, there are four primary ways that government in the U.S. subsidizes housing for low-income individuals:

1. Public housing directly owned and operated by government entities. The U.S. used to build a lot of it, starting in the late 1930s, but by the 1960s, the federal public housing program was facing a perfect storm of problems: racial segregation, underfunding, mismanagement, severe crime and social ills, and the general socioeconomic collapse of working-class neighborhoods amid white flight and the rise of the suburbs. Due to the intense stigma associated with "the projects," most cities with large, high-rise public housing complexes have demolished them — the big exception is New York City, where many still exist and house more than 400,000 New Yorkers. (A lot of the stigma that still follows public housing today, for the record, is based on outdated stereotypes, and there's evidence that most of it actually works quite well.)

2. Project-based housing subsidies, which entails paying a developer (often a nonprofit organization) to build housing and rent it out to income-screened tenants at a reduced rate. This is the premise of the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, which has resulted in about 2.7 million rental homes since 1987. Would you believe that the biggest single provider of federally-subsidized housing units in the United States is the IRS?! Strange but true.

3. Local rent regulation, including inclusionary zoning (requiring developers to include a share of affordable units in their projects) and rent control (capping allowable rents or rent increases). These are ultimately indirect subsidies, paid not out of a governmental budget, but out of the profit margins of land owners and developers and the rents of market-rate tenants, which are affected by the additional regulation. There's a lot of debate over what and how great the unintended consequences might be — of particular concern is that if these policies depress the production of new housing, most or all of their benefits might be canceled out. Economies are complex systems, and the indirect consequences of regulation can be wickedly hard to predict.

4. Housing vouchers — a direct subsidy which follows the tenant/household, rather than the housing unit itself.

Today I'll give an overview of housing voucher programs, their history in the United States, what they do well, and what they don't do well. This is not to say that the other options don't have their place in providing affordable housing, just that they'll have to be a topic for another essay and another day.

A Brief History of Housing Choice Vouchers

The federal Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program, better known as Section 8, was established by the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974. It was strongly supported by conservatives in Congress as a market-based, more economically efficient alternative to traditional public housing, which was, by then, widely viewed as an albatross. Instead of directly subsidizing housing units, the federal government would subsidize the rents of low-income households, who would be free to take their vouchers and live wherever they saw fit. Landlords would have to compete with each other to offer attractive rentals. Consumer choice would be enhanced.

Housing Choice Voucher recipients pay no more than 30% of their income in rent. (This number was increased from an original 25%.) The federal government makes up the difference, and the landlord thus receives the same market rent she would have gotten from a non-voucher tenant.

Vouchers can be used for any rental unit (where the landlord chooses to accept them) up to what the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) determines is the Fair Market Rent (FMR) for a given metropolitan area. The FMR is intended to be the 40th percentile of asking rents for recent movers in a region; no taking your voucher and living in a penthouse suite.

The most significant changes to the program since its inception have involved portability. This refers to the ability to take a Housing Choice Voucher obtained in one city (local housing authorities are responsible for issuing the vouchers) and use it in another city or even state. Portability has been gradually expanded in response to the fear that voucher holders would be trapped in poor communities, unable to move to pursue opportunities without sacrificing their vouchers. By 1999, portability was made nationwide: you could receive a voucher in Seattle and use it in Dallas if you wanted to.

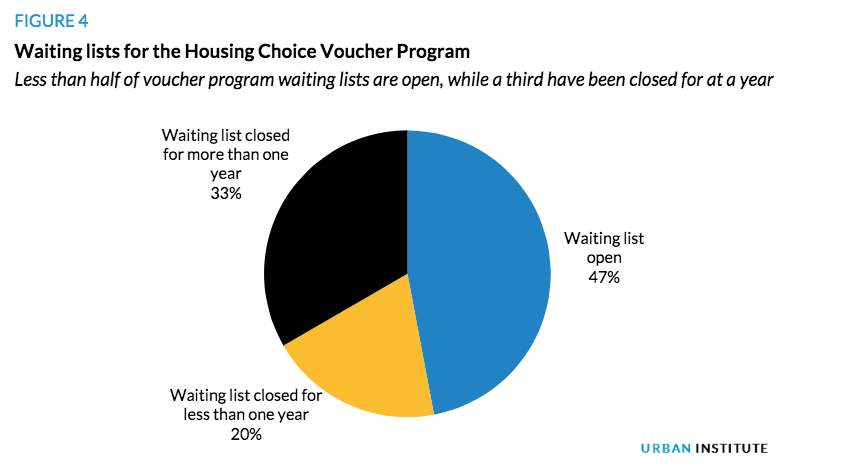

Source: Urban Institute

The most consistent story of Housing Choice Vouchers in recent decades has been drastic underfunding relative to demand, and long waiting lists as a result. The statistics are staggering, as the 2016 report "The Long Wait For a Home" by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition describes:

Local data paint a bleak picture of long waits for housing assistance. The Charlotte Housing Authority in North Carolina, for example, has more than 31,000 applicants on its HCV waiting list, yet only 200 to 240 vouchers become available every year to new recipients (Clark & Kemp, 2015). In Baltimore, 74,000 applicants applied for a chance at getting on a waiting list of 25,000 for a voucher. Only 1,000 to 1,500 vouchers become available in Baltimore each year (Wenger, 2014). At that pace, it would take more than 16 years to offer housing assistance to the households lucky enough to get on the wait list.

This issues are not unique to a handful of cities. They are universal. The median HCV waiting list has a wait time of 1.5 years, and 25% have wait times of 3 years or longer. As a result of this and other barriers, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that only 1 in 4 households eligible for federal rental assistance receives it. If you're into data, you can take a deep dive here.

These problems notwithstanding, Housing Choice Vouchers serve about 2.2 million households nationwide.

What Do Vouchers Do Well?

Housing Choice Vouchers succeed in four key areas:

1. They get people into homes. Many of these people would otherwise struggle to afford housing. Some would be homeless. Some would risk eviction, perhaps becoming among the 83 million American evictions since 2000 documented by Matthew Desmond's Eviction Lab. Just under half of households served by HCVs are families with children. There is abundant evidence that stable housing is essential for children's educational outcomes.

2. They expand people's options (to some extent). Voucher holders live in less economically and racially segregated environments than public housing residents, though they are still disproportionately likely to live in poor neighborhoods, for reasons I'll get to momentarily.

3. They are more cost-effective than other forms of housing subsidy. A recent Rutgers study (worth reading, with some interesting graphs and charts) estimates that for every taxpayer dollar spent on voucher programs, households receive a benefit that they value somewhere between 80 and 90 cents, compared to 40 to 60 cents for project-based programs such as public housing. The basic reasons are twofold: voucher programs have less administrative overhead, and voucher programs give the recipient greater flexibility in choosing where they want to live based on highly individual priorities, thus maximizing their personal "bang for the buck."

4. They allow market price signals to function. There is an ongoing, acrimonious debate in housing policy circles about where project-based housing subsidies, such as LIHTC, should be concentrated. Do we situate these projects in places where the need is currently greatest, at the risk of further concentrating poor people in disadvantaged neighborhoods? Or do we deliberately build such housing in wealthy suburban areas as a way of deconcentrating poverty, at the risk of isolating its residents from their prior social networks, and possibly housing them in communities where access to jobs and social services is difficult (especially without a car)?

What if your metro area's geography of opportunity changes dramatically over the coming decades? Right now, it might seem a no-brainer to build low-income housing in the suburbs that have the best schools and the most robust job markets. But how many of those suburbs will still have the best schools and the most robust job markets in a generation? How many will fall into decline? How sure are you?

If our poverty-alleviation policy is focused on encouraging people to abandon currently poor neighborhoods (many of which are the most fiscally solvent places left in our cities), on the presumption that those neighborhoods are "bad" places to live, then what becomes of those neighborhoods? What's the end game for the place itself?

Delivering more housing dollars in the form of vouchers makes it possible, in theory, to sidestep much of this debate. We don't need to tell low-income people where it's best for them to live. We don't need to make accurate predictions about which communities will be desirable in the future. We don't need to make paternalistic assumptions about which communities are undesirable right now. In theory, vouchers expand choice. End of story.

Practice is, of course, more complicated than theory.

What do Vouchers do Poorly?

Housing Choice Vouchers fail in five significant ways:

1. They fail to provide housing in tight markets. Landlords can decide whether to take Housing Choice Vouchers at all. In a high-vacancy environment, it's a no-brainer to accept them: it's a guaranteed rent check each month, which Uncle Sam can pay even if your tenant gets laid off. In a tight market, on the other hand, landlords have no trouble finding tenants. So why bother with vouchers? Why deal with the bureaucracy, the inspections, the added risk? The result is not just a shortage of vouchers for those who want them, but a shortage of rental properties that will accept them.

Source: Rocky Mountain PBS News

In the mid-1990s, Minneapolis demolished over 1,000 units of public housing, and gave many of the displaced residents Housing Choice Vouchers as compensation. A Legal Aid attorney at the time remarked that in the extremely tight rental market of the Twin Cities at that time, "Giving a family a voucher is like giving them Confederate money."

2. They fail to promote broad desegregation and mobility goals. The vast majority of Housing Choice Voucher recipients remain in neighborhoods with significant concentrated poverty. There are a couple reasons for this.

One is that they may simply choose to, for valid personal reasons. Low-income people depend heavily on social capital to make up for their lack of financial capital: for example, leaning on family and friends for child care, knowing a guy who can give you a ride when your car breaks down, and so forth. Being uprooted from your community is hard, and the trade-offs aren't as obvious as they might seem to an outsider. For every person who is eager to leave a "bad" neighborhood, another wants to stay.

The other reason is that the number of rental units that are available to voucher holders can vary tremendously by neighborhood and by city within a region. A survey conducted a few years ago within the Twin Cities suburbs is illustrative: the wealthy city of Minnetonka had 3,900 units of rental housing. 45 of them were available to voucher holders. The similarly upscale suburb of Edina had 3,006 rental units, with precisely zero open to HCV holders.

This is not necessarily because of discriminatory attitudes by landlords. Rather, it can be a function of the Fair Market Rent calculation that HUD uses to identify eligible units. In poor parts of a region, most apartments might be below that 40th-percentile rent. In affluent parts, very few, if any, might make the cut. The end result is that vouchers alone fail to open up exclusionary, affluent neighborhoods to the low-income people their land-use policies were likely designed to exclude in the first place.

Could the Fair Market Rent for a voucher holder be set at a different level in different cities or even neighborhoods, rather than a metro-wide ceiling? Possibly, but this carries the potential for perverse incentives to move where you can get a better deal, and would likely raise the cost of the overall voucher program significantly.

Will neighborhoods like this one forever be out of reach of the average or low-income American? (Photo source: Johnny Sanphillippo)

3. They're politically vulnerable. Project-based housing subsidies have one crucial advantage over household-based subsidies: they have a broader political base of support. The construction industry likes them. Developers like them. Vouchers, on the other hand, have one constituency: voucher recipients.

4. They're hard to scale down to local control. Local programs are more responsive to local conditions, and less vulnerable to changing political winds in Washington. But there are very few local housing voucher programs. (Denver is the only significant example I could find.) One reason for this is clear: the difficulty of determining and enforcing eligibility. Do you restrict it to people who can prove long-term residency in your city? Or can new arrivals move there and apply for a voucher the next day? If so, the local taxpayers funding the program might see more than a little reason to object.

5. They're hard to scale up to cover more of the population. Most eligible households already can't get a voucher. Waiting lists are long. There are proposals out there to turn Housing Choice Vouchers into an entitlement program — meaning that instead of there being a limited pool of funds, everyone who is eligible for a voucher would automatically get one. There are even proposals to expand eligibility to people making more money than currently qualify.

One such proposal comes from our good friends at City Observatory. Another, here, has been advanced by eviction scholar and celebrity-sociologist-of-the-moment Matthew Desmond.

There is an outstanding question about whether dramatically expanding the amount of voucher money out there would lead to rent inflation, undoing many of the gains. Think of how the easy availability of student loans has contributed to college-tuition inflation: if you know your students will be able to take out loans to cover whatever you charge them, why not raise tuition? If you're a landlord and you know your tenants can get vouchers, why not raise rent to the maximum level the voucher program will cover?

This was suggested by critics when the program was created in the 1970s, but for the most part, there is little evidence of such rent inflation. But that might be because of the relatively small share of vouchers in the overall housing market.

A Question of Political Will?

Right about the time I was wrapping up this article, HUD Secretary Ben Carson announced a plan to raise voucher recipients' rent contribution from 30% to 35% of their income, and impose additional work requirements. The backlash from tenants' advocates is already strong, but it's a perfectly timed illustration of the tenuous status of federal housing assistance. Clearly, we are far from any political moment in which vouchers are about to become a new entitlement program.

Perhaps more importantly, the prospect of a voucher program, or any other form of government housing assistance, doesn't let us off the hook from asking this question: If there’s a huge share of the population that the market isn't provide adequate housing for, why not?

The reasons are manifold, and have to do with the unintended (and intended) consequences of land-use regulation. They have to do with the ways we've prevented desirable neighborhoods and cities from incrementally growing and intensifying. Ultimately, they have to do with the contradictory expectation that housing will be both broadly affordable and a good investment vehicle. Daniel Hertz nailed this paradox a couple years ago in The Atlantic:

These two ideas are almost entirely mutually exclusive. The first essentially says, “Use housing policy to keep home prices down”; the second says, “Use housing policy to keep home prices up.”

Until we address this root contradiction, treating housing unaffordability one tenant at a time, or one unit at a time, is always going to be inadequate. The rising tide of home prices feels pretty good if you bought your home in the right decade, but it's increasingly clear that this rising tide swamps all boats.

(Top photo source: Johnny Sanphillippo)

Utah, like many places, has an affordable housing crisis. These 5 strategies can deliver solutions…for Utah and beyond.