Does your Town need its own Currency?

Andrew Wilson is a Strong Towns member and world traveler with an interest in money and history. Today he's sharing a guest article about local currencies.

Strasbourg (Source: Ignaz Wiradi)

After several years of living in Strasbourg, France, I began to notice a new set of colorful little stickers on local business windows. “Le Stück accepted here,” they said. I paid little attention at first, as the doors of every eatery on the street were already populated by such insignia: “Chèque déjueuner,” “Ticket Restaurant,” etc.: meal subscription programs purchased, tax-exempt, by employers—a kind of capitalist concession to the communist worker’s cafeteria. Not the worst sort of subsidy, gustatorily speaking.

But “Le Stück” stood out as something different, for it could also be spent at grocers, bike shops, web-development consultancies, yoga studios, bookshops, architects, psychotherapists, and even a few market gardeners. It was, in fact, a whole new, local currency. Cute, I thought. “Euro” is such an anodyne, bureaucratic name. (Imagine “Americans” instead of Dollars. Much too honest.) Le Stück, by contrast, was full of regional flair, made to order for this Franco-German border city. It's the French article "Le" out front, followed by the Alsatian "Stück" for “piece, morsel, loaf, coin”; and indicated by an S, like for the US dollar or Superman, but with an umlaut on top.

Le Stück is a community or cooperative currency. You buy Stück with Euros one-for-one at a bureau of exchange and spend them at any subscribing enterprise. It’s like a “buy local” gift card but on steroids. Businesses, too, can use their Stück wherever Stück are taken; they can pay their workers, rent, and (eventually) city taxes. At the moment it’s only cash, but the backers hope that electronic Stück will soon be minted. And if the money becomes widely enough used, whole swaths of Strasbourg’s daily life could be managed without reference to Euros at all.

(Source: lestuck.eu)

Getting your Euros back from Stück, however, costs 5%. Part of this so-called malus helps fund the system; another part goes toward selected local causes. But it’s also meant to encourage circulation within the system.

It makes a kind of homeopathic sense: support your like-minded neighbor’s business, keep the money circulating at home. But I was a trifle suspicious all the same. Beneath the lofty local rhetoric lurked a trite indictment of faceless, earth-destroying global trade. Was Le Stück but a slightly higher-minded breed of trade protectionism? The Euro, for all its blandness, was a boon for me, a foreigner and frequent traveler: no more fleecings at bureaus of exchange, no more off-the-cuff arithmetic. Using Euros at multinational businesses had certainly helped my family’s bottom line, from functional Swedish furniture right down to Cretan olive oil. A strictly local currency seemed like a step into the past, not toward the future. But there must be some other story to tell.

Local Currencies Around the World

Le Stück is not alone. Far from it. Other cities, villages, and even states have jumped on the local currency bandwagon, spicing Europe’s monetary monoculture with a delightful pageant of place-specific notes. Basque country has the Eusko, Montpelier its Graine, Nancy Le Florain, and many other French locales belonging to the alliance of Monnaies Locales Complémentaires Citoyennes. Madrid has its Boniatos, Seville its Pumas. In Geneva and environs you can pay with Le Léman. Germany boasts the whimsical Rheingold (hopefully with less epic drama than the opera) and the stodgier though much more widely circulated Chiemgauer, which deliberately loses value over time (demurrage) to discourage hoarding. No more mattress stuffing!

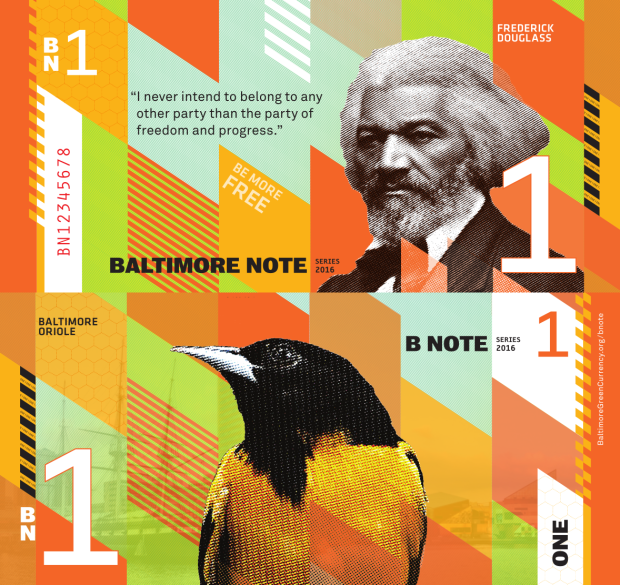

The idea of local currency is even older on this side of the pond, as I soon discovered. There’s San Francisco’s Bay Bucks, DC’s Potomacs, Berkshire County’s BerkShares, Baltimore’s BNote, not to mention Davis Dollars, Ithacash, Hudson Valley Current, NYC Particle Notes, and a host of others more and less viable. According to the Complementary Currency Resource Center, there are now over 5000 of them in various stages of development and use. The European Union has even funded research and published a booklet of best practices; a large conference just took place in Barcelona, where economists and activists from around the world gathered to discuss and dispute alternatives to our current monetary system. This can hardly be called a fringe movement.

A commonly cited tale of inspiration comes from Curitiba, Brazil, where residents were paid in bus tokens for collecting the trash that choked inaccessible favelas. The slums were cleaned and the city’s empty buses filled, taking residents to work and school. But even more noteworthy, the tokens soon became new media of exchange, usable for food and school notebooks and even to pay for select city services. Similar schemes were then devised to redevelop historic buildings, create new housing, and establish parks, all with little external expense or debt on the city’s balance sheet. For many city projects, it turned out, there was no need to use the standard financial system at all.

Bernard Lietaer, economist and doyen of the concurrent currency world, says that these innovative currencies can work wherever unmet needs can be matched up with unused resources. Frequent-flier miles are perhaps the best-known example, but there are less bland options: in Japan, far-away adult children can trade time taking care of local elders with other adult children back home.

But do they work?

Despite this robust imprimatur, economic doubts remain. There’s a lot of “eco,” “ethical,” and “solidarity” in this alt-currency world, fine civic virtues in themselves, but almost always marinated in a healthy dose of soft apocalypticism. Many monies trace their origins to Transition Towns or some other movement’s peak-oil concerns—imagining, much like James Kunstler’s World Made by Hand books, life after global capitalism’s collapse. If they’re not planning for the age of Aquarius, alt-money makers are preparing for catastrophe: left-wing-preppers of a sort.

Successful predecessors to today’s alternate currencies testify to this tendency: Wörgl in Austria, WIR in Switzerland, scrip used in Depression-era USA, un-cashed checks in 1970s Ireland, and lending clubs in Argentina’s 2001 banking collapse. These alternative currencies emerged in times of capital famine, working wonders to facilitate employment, exchange, and even investment in infrastructure: a bridge built during the brief period still stands in Wörgl. That is, before these currencies were outlawed, went belly up, or ran their natural course as national currencies regained stability. Only WIR remains in use. Perhaps the world isn’t bad enough.

With so much creativity and proven results, what’s not to like about alternate currencies? It’s not so much the monies in themselves, but the constellation of unfounded dogmas they attract. For one thing, there’s a mercantilist suspicion of trade deficits. Local boosterism to the contrary, a region’s fortunes are fostered neither by accumulating gold nor by strictly local circulation but by specializing within the broadest possible market. Hindrances to trade tend to impoverish everybody.

“A local currency alone will not unravel these accumulated false incentives.”

There’s confusion, too, about who benefits from said local circulation. It’s not actually true that money spent at a small grocery magically stays local. Even corner grocers order almost everything in their stock from afar; concurrently, the savings from big-box stores “stay local,” too, just in the pockets of consumers. Which is to say that money doesn’t “stay” or “go” from places like copper or crude oil.

If there’s any mining going on by big-box retail, it’s in the political economy, not in trade per se. Cities cave like dominoes to X store’s promises of employment, growth, traffic, and tax revenue, all the while ignoring the infrastructure obligations they assume. To this de facto subsidy is added another: the criminally unfair rule of “accelerated depreciation,” which pushes builders toward greenfields, favors disposable buildings, and penalizes redevelopment. Main Street flounders at this onslaught, and its economic fabric frays. A local currency alone will not unravel these accumulated false incentives.

What Local Currencies Could Accomplish

And yet a local currency might actually help, though not by “keeping things local” as ecolutionaries imagine. Jane Jacobs’s Cities and the Wealth of Nations criticizes national monies not only for their imperialistic character but because their relative value tends to track a nation’s dominant trade. Hence the recently fantastical prices for real estate in boom-town Luanda, while the rest of Angola languished. Jacobs cites the former Czechoslovakia, where industrial powerhouse Prague impeded the competitiveness of Slovak agriculture, and not merely based on ethnic prejudice. Singapore and Hong Kong, by contrast, are the unmistakeable successes.

(Source: Neil Theasby)

The result is that secondary cities and industries suffer from the financial asphyxiation of a currency tied to the frontrunners. Were cities and their regions to manage their own currencies, Jacobs argues, then imports, exports, investment, and debt would work to foster rather than inhibit innovation and “import replacement.” A region excessively dominated by imports and suffering lack of capital infusion, would see its currency devalue, making imports more expensive and its exports more competitive in the wider market. That region’s city, its engine of ingenuity, would then generate alternatives to expensive imports--which would themselves become competitive exports.

More than one economist has gone completely mad trying understand how money works, and it may turn out that Jacobs is just off base. It’s notoriously hard to test. But the gaps now growing within the Eurozone suggest that money is perhaps less like a meter or a kilo than central bankers (and Constitutions!) imagine. A truly local currency—broadly adopted—might just provide proper, rather than distorted, price information to local producers and entrepreneurs.

Friedrich Hayek suggested something parallel in his later years, though less for regionalism than for his skepticism of centralized control. A whole branch of theoretical and historical economics supports free banking, a world where Central Banks compete for fealty and funds with private moneys of all kinds and from all places. Time would tell which system works and weathers shocks better. According to Hayek, currency competition, now effectively illegal, would lead to a more reliable, more stable, and (admittedly) more confusing fiscal world. It’s certainly a far cry from the heavy centralization and regulation of today.

It’s also a far cry from the eco-solidarity imagined by today’s local money activists. They have it right that money is, above all, a social technology, less like gold and oil in essence than like language or arithmetic. They also recognize the power of markets to coordinate elaborate networks of credit and obligation, and give a nod to the important role of prices in communicating vital information.

Yet, in acknowledging money’s inherent flexibility, there’s a tendency to try and steer its unruly character toward predetermined ends. This may work briefly for small bands of local and like-minded people, and we certainly should not disparage new monetary experimentation. But if there’s anything the history of money teaches, it’s that people find a way to get what they want, with whatever currency is available. In imagining a different, better, future for our towns and cities, there are many, far less baffling matters to keep in mind.

I just wrote some friends in Strasbourg, asking if Le Stück is much in use. No, they said, lamentably. It seems to have remained a bright and distant dream.

(Top image source: TriviaKing)

Related stories

About the Author

Andrew Wilson is a writer and freelancer living in Saint Paul, MN. His recent book, Here I Walk, recounts his thousand mile walk from Erfurt Germany to Rome, following the historic steps of Martin Luther. In addition to writing about Money and Reformation History, he's also lobbying for a freeway cap over I-94.

Abby is joined by Edward Erfurt to discuss the recent vote to turn Boca Chica, Texas, into a new official city called Starbase. (Transcript included.)