What Does a Strong Towns Master Plan Look Like?

Kevin Klinkenberg (Twitter: @kevinklink ) is a Strong Towns member who is Principal at K2 Urban Design and blogs at The Messy City.

Let’s be frank. There’s some real tension between the “do lots of small things” approach emphasized by Strong Towns and the “do big things” approach that’s baked into our current planning and development professions. We are hard-wired for bigness today. Big dreams, big ideas, big money, big government, big corporations. Bigness is deeply American, and arguably has been for generations.

Can this tension be resolved? Is it one approach or the other?

I’ll admit I have a bias towards both-and, instead of either-or. Living enough years teaches you that life is rarely simple or clear cut. And, there’s a place for everyone and everything. I do, for example, believe very deeply in the Strong Towns approach, the goal of iterative processes and incrementalism, and a general attitude of taking ownership of change in your own place. These are deeply important, and American society has largely strayed away from these mindsets to our own misfortune. It’s imperative for today and for tomorrow that we find our way back to the approaches so well described on this website and the new book.

But I also remain steadfast that humans need to dream big occasionally, and to have a sense of what the big picture could be. It’s a very human quality to have aspirational visions of the future. George Bailey, in It’s a Wonderful Life, epitomizes this notion with his constant desire to do big things. That’s a core part of his internal struggle as a character, and one reason I think the movie is so relatable to people in all times and places.

In the planning world, it’s why we are drawn to Daniel Burnham’s famous quote,

Make no little plans — they have no magic to stir men’s blood.

If you turn to the following page on the Plan of Chicago, though, you’ll see Burnham’s qualifier, which says,

It should be understood, however, that such radical changes as are proposed herein cannot possibly be realized immediately. Indeed, the aim has been to anticipate the needs of the future as well as to provide for the necessities of the present; in short, to direct the development of the city towards an end that must seem ideal, but is practical.

In essence, big dreams are really important, but, hey, let’s be practical and work incrementally.

But what do we remember? That first quote. It’s very American. A popularized version of what Burnham said is what Casey Kasem used to close with on every episode of American Top 40, which I used to listen to weekly as a kid, “Keep your feet on the ground, but keep reaching for the stars.”

It’s that very human tension that makes me wonder, “What would a Strong master plan look like, when master plans by nature are about big dreams and big actions?” A great deal of big plans, fanciful renderings and utopian schemes are rightly pilloried on this site. We’ve had more nightmares than successful dreams in recent decades. But none of that stops our desire to want to dream, and the reality that many people get up every day and actually do big things — either in the public or private sector. What shall we say about that, in an effort to offer productive solutions for our cities and towns?

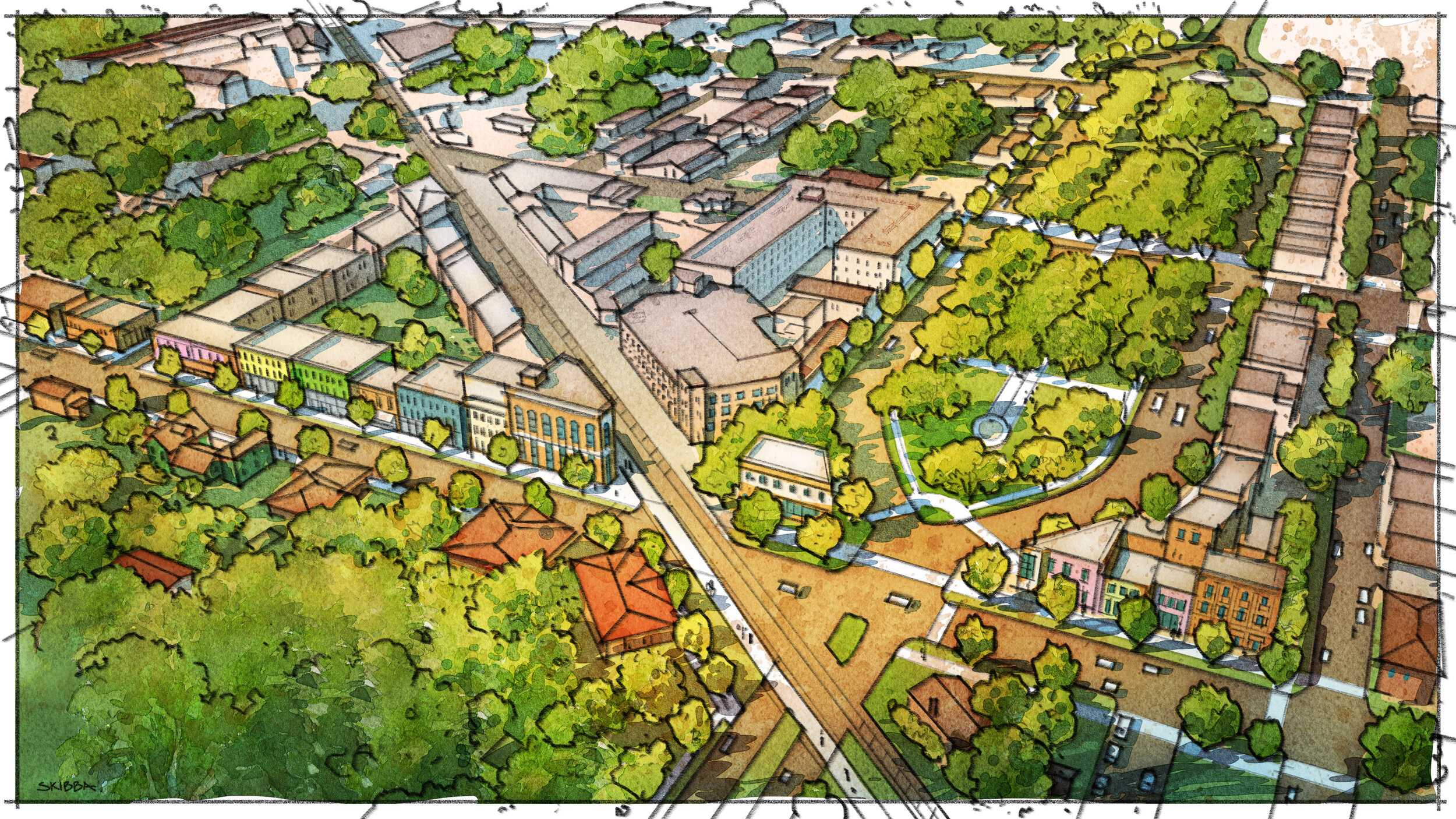

Savannah plan.

Those questions were a part of what a team of us tried to answer with a recent downtown master plan in Savannah, Georgia. Savannah, in fact, is a potential case study as a way forward.

The city was conceived by Gen. James Oglethorpe as a very idealistic, almost utopian human settlement. Thomas Wilson’s book, The Oglethorpe Plan, is probably the most complete resource on the social, physical and economic ideals of Savannah. What evolved on the ground after Mr. Oglethorpe left and returned permanently to England in 1752, is a classic example of a bold but simple plan, and a very gradual, incremental implementation over many decades. Oglethorpe’s complete transect of human settlement, most realized in a plan of a series of wards, built around a public square at the center, was a really big idea. It was ambitious, aspirational and steeped in Enlightenment ideals.

It was also very simply platted in a uniform pattern of 60’x90’ lots that have been built, modified and rebuilt by thousands and thousands of people over nearly three centuries. The results are magnificent. It’s not just beautiful and walkable, but the historic core is financially resilient and productive — the epitome of a strong town.

We can find similar bouts of hopefulness combined with practicality throughout American history. Virtually every city or town has what is effectively a marketing poster that looks something like the one from Lawrence, Kansas. Lawrence was largely settled by New England abolitionists (the main street is Massachusetts Avenue), in an effort to create a bulwark against the expansion of slavery. What you see in the poster, and many like it, is a bold and daring notion of what this place could be (come move here!) combined with a gradual, incremental and simple approach to day-to-day building.

Keep your feet on the ground, but keep reaching for the stars.

The new Savannah downtown plan, completed as a community-led effort and recently adopted by City Council, uses a similar mindset. Today’s situation is much more nuanced and challenging than 1733, so by nature the specific answers are complex. It’s also necessarily couched in the terminology of the moment. Boiled down to its core, however, it sounds familiar: it’s a series of aspirational notions of what the place can evolve towards, combined with a series of practical steps towards implementation. Those steps are a combination of many small actions and a few very big ones. It has a series of five key goals, some of which sound familiar to many plans:

Connect people and neighborhoods with the street grid

Expand public space and make it a cornerstone of city life

Focus on active transportation

Prioritize quality of life over commuting time

“Legalize” Savannah by enabling the original incremental, built pattern to be built again by-right.

So what makes this unique or strong? I’d suggest it’s that element of both-and, instead of either-or. It’s fundamental in nearly every community I’ve been to that doing the little things, the incremental change, is far too difficult and expensive. Master plans need to not just understand this, but figure out how to truly enable it. This should be job one. But we also have some big efforts to undertake, too. Unwinding some of the destructive ideas of the 20th century by nature requires some big money and some big change. Let’s harness this to the productive advantage of our communities.

Let’s also not minimize that people need to have an idea of what their individual, small efforts could add up to over time. That’s a very human reality. The idea of the beautiful rendering isn’t to say a street or block or place will look like this; rather, it’s to say this is the direction we are headed in together. This is what is possible, if we motivate our many small actions and a few big ones.

I’d suggest a few key mindsets when thinking about what a Strong master plan could be:

Use time-tested principles for city-building & design

Understand and do the math

Enable lots and lots of small, incremental change by many hands

Find some opportunities for big, aspirational change

Identify a series of first steps to test that are inexpensive

Most importantly: don’t take years to complete a plan, since this just wears people out and builds cynicism. Radically shorten the process, especially by using the NCI charrette model.

Many, many more of our “solutions” to today’s problems do need to be found by enabling bottom-up creativity and action. We unwittingly stifle far too much creative and productive activity with a dizzying maze of bureaucracy and regulation, even though much of it is well-intentioned. But it’s also true that some problems simply require top-down, coordinated solutions. Some issues are so complicated or expensive that there isn’t an incremental step forward. We need to find room for those solutions, too.

When cities attempt to prescribe the exact way a building must be used, they risk regulating away the very life of a place.