Who Pays for Growth in Collier County, Florida: Part 3

This is the third in a five-part series of articles about how new planned development in Southwest Florida’s Collier County perpetuates an insolvent and destructive model of growth, despite the existence of policies that claim to prevent that very problem. Read part two here, and part four here.

Part 3: Who pays for new water infrastructure?

Another water treatment facility in Florida. Image via Flickr.

Providing water to a fast-growing place like Collier County, Florida is not cheap. One major consequence of the proposal by private developer Collier Enterprises to build three massive new "villages," far from existing population centers, is that it will require the realization of longstanding plans to create a major new combined potable water and wastewater treatment facility—the county's third—to serve the region's remote northeastern corner. Land for this facility was purchased all the way back in 2003, then plans were shelved during the Great Recession and revived as growth picked back up.

To lay out the stakes clearly: Collier County, in response to a proposal for 8,000+ new homes in three spread-out, gated subdivisions, is poised to spend over $200 million extending utilities to a whole new, previously rural, portion of the county.

The new facility is being funded by debt. In 2019, the Collier County Water and Sewer District issued over $76 million in revenue bonds specifically for the northeast expansion, with more to come. Most of the debt will be paid back out of water customers' monthly bills. It will be added to preexisting debt service, which over Fiscal Years 2021-2025 is projected to account for $49 million out of the utility’s $283 million total expenses. (See page 63 of the county’s 2020 Annual Update and Inventory Report.)

Debt in itself isn't bad, or in any case avoidable. The nature of modern water infrastructure is that large increments of investment are necessary, because building many small treatment facilities is far less cost-effective than building a few large ones. But debt is a tool to be used sparingly and prudently, to spread out known and supportable costs over a manageable time frame. And so, the question becomes, how can we be sure that the costs the agency is incurring are supportable in the long run?

There is reason to ask. Florida cities and counties in particular have a long history of underfunding the maintenance of water infrastructure, only to run into huge problems down the line as the system ages. In 2019, for example, Tampa announced that it would spend $3.2 billion over 20 years to fix its many failing water and sewer pipes, raised in part by more than doubling utility rates and in part by taking on $1.5 billion in new debt. Tampa is not alone: all over Florida, from metro Orlando to Sarasota, water and sewer utilities are dealing with aging infrastructure, leaks and spills, and raising rates to cover the repairs.

Unlike Tampa's, Collier County's rapid growth is a recent phenomenon: the county population has more than quadrupled since 1980. Much of its water infrastructure has not yet aged enough to begin failing, meaning the utility’s fiscal position currently looks strong, and so does its AAA bond rating. (Bond ratings, keep in mind, are for investors, not taxpayers; they are a prediction that the utility will not default on its debt, but say little about whether customers will experience stable rates or high-quality service in the process.)

As the system ages, whether Collier County can afford debt service and maintenance on the old pipes, and eventual maintenance on the new pipes, without substantial rate hikes for water customers will be an important question to get right.

At Strong Towns, we've long observed that most postwar development in America follows a financing model that can be likened to a Ponzi scheme. Not in the sense of criminal fraud, but rather in the sense that new growth is endlessly required to keep up with the liabilities generated by previous iterations of growth. With that concept in mind, see if this statement from Collier County's utilities finance director (page 26) doesn't sound familiar:

A growing utility ensures a steady future stream of user fee revenues that will use -- that will be used to rehabilitate aging infrastructure anywhere in the system, and most likely that's going to incur -- that's going to occur in the older western urban service area. So a growing utility has that benefit.

A map from the 2020 AUIR report shows the locations of existing water/sewer service, and (in light blue) new northeastern service including to the planned Collier Enterprises villages.

It's obvious that the water utility is aware that there are limits to the costs it can cover. The massive Golden Gate Estates has never had water or sewer service; its over 20,000 residents use well water and septic tanks. When the county actually studied the feasibility of extending utilities to the scattered homes on pre-platted lots in the Estates, it reached the jaw-dropping conclusion that it would cost over $100,000 per connection. This was a complete non-starter. A minimum clustering of population is required to justify laying pipes in the ground. As utilities finance director Joe Bellone put it to the Planning Commission in April:

“I think about it as the more people you put on an airplane, the greater the revenue. The more connections we can have per mile of pipe, the more fiscally feasible it becomes to provide that service.”

It’s notable that the sentence above makes the case for truly compact and connected development, of the sort that the proposed new villages are supposed to be but aren't.

Bellone did claim in the same testimony that the new northeast facility is fiscally feasible. But the actual analysis provided to the public does not make it easy to verify that or form one's own conclusion. It turns out that the county's mechanism to ensure the solvency of new development is severely lacking in teeth or rigor.

How neutral is "fiscal neutrality"?

As we've seen in the first two installments of this series, one of the hallmarks of planning in Florida is a highly technocratic approach to growth management, in which armies of consultants and lawyers work to make large-scale new development compliant with elaborate regulatory frameworks. One example of this is the requirement that major development proposals demonstrate fiscal neutrality. Collier County's land development code is extremely unambiguous about this. From Section 4.08.08.L. 1:

Demonstration of Fiscal Neutrality. Each SRA must demonstrate that its development, as a whole, will be fiscally neutral or positive to the Collier County tax base.

The plain English meaning of this is that new development must not result in increased costs for existing taxpayers, relative to a scenario in which that development does not occur. The way it's implemented is that counties set impact fees paid by developers, which are intended to cover one-time capital costs associated with growth.

Collier County’s Impact Fee methodology for water utilities.

For example, suppose a large new development requires the construction of a new fire station, a couple public park facilities, and a water treatment plant, and the widening of a number of small rural roads to accommodate suburban traffic volumes. The impact fees should cover the new development's share of the cost of building those things. That share won't and shouldn't be 100%, because existing residents will also benefit from them. So cities and counties conduct elaborate impact fee studies to determine the proper proportional share of virtually every capital expense under the sun. In theory, this is to ensure impact fees are internalizing the costs of growth, without overcharging developers (and therefore, indirectly, the residents of new homes) in order to give longtime residents a subsidy.

In theory.

"Neutral" up front or over the life cycle?

If you're a regular Strong Towns reader, you've already spotted a huge problem with the framework above, and a basic problem with impact fees that I've written about before. They only cover the initial construction. Once a pipe or other facility is in place, it needs to be operated and maintained in perpetuity, and eventually replaced when it fails. These costs will not come out of impact fees, but general sources of revenue. It is entirely possible for new development to be "fiscally neutral" with regard to the up-front capital costs, but fiscally negative with regard to the long-run operational and maintenance costs. Those costs will be passed on to everyone else who pays into the system.

Collier County requires no meaningful fiscal neutrality analysis for water.

It is the developer's job to hire a consultant to do an economic assessment, including evaluating fiscal neutrality for each of a long list of public expenditure categories (roads, schools, police and fire, parks, public utilities, etc.). When I got to the water section for Longwater Village's assessment report, I stared at it for a long time, thinking I was losing my mind. One thing you won't find in that assessment: any attempt to actually show that the village is fiscally neutral, even with regard to new capital expenses alone. The report looks like this:

A table showing the anticipated water and wastewater demand, per capita and in total, for the village.

A statement that the developer will be paying its impact fees.

The statement, "Longwater Village is deemed fiscally neutral with respect to Collier County’s Water and Wastewater capital and operating impacts."

This is as incoherent as evaluating whether your household budget is sustainable by only examining your income and not your expenses, and concluding, “Well, I make $75,000 a year, so I’m sure things are fine.”

The reason they get away with this is semantic. The Collier County Water Sewer District is a separate entity that operates as an enterprise fund: that is, it operates like a business, and sets user fees (your water and sewer bill) at a level that covers its expenses. Because of that, water and sewer customers in Collier County (and most places) are technically not considered taxpayers. They're ratepayers. And because the fiscal neutrality ordinance refers to effect on the "tax base," the county's position is that fiscal neutrality does not apply, really, to water and sewers. The whole report is just a strange formality.

But this does not answer the question of whether ratepayers’ bills will eventually have to rise to subsidize new development. A shortfall is a shortfall, and if there is one, somebody will foot that bill.

The actual costs are elusive at best.

Any attempt to evaluate the actual fiscal neutrality of new water infrastructure quickly runs up against assumptions that are maddeningly opaque. The easy part is calculating the impact fees that the developer owes. The hard part is identifying the true costs of the infrastructure.

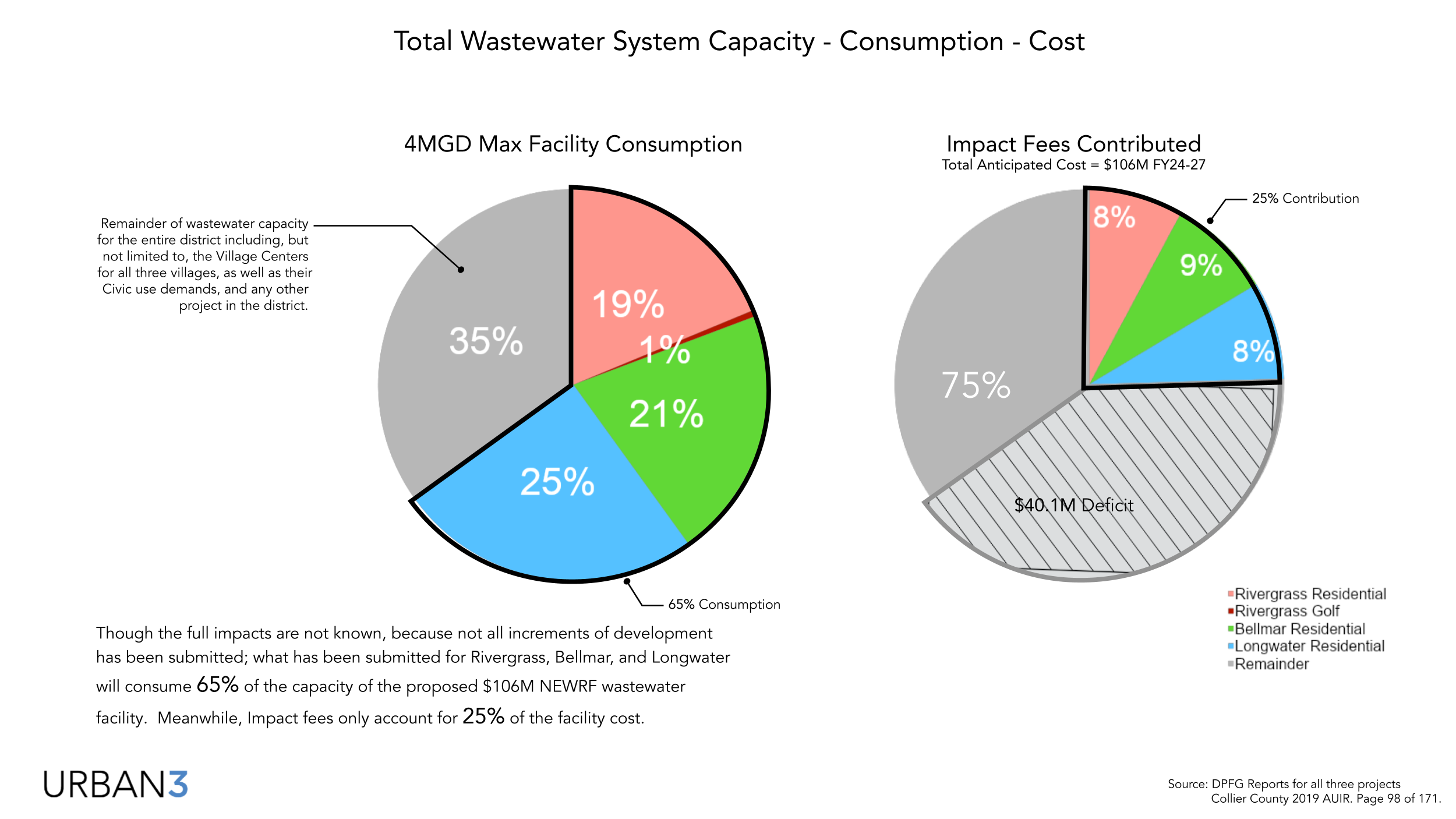

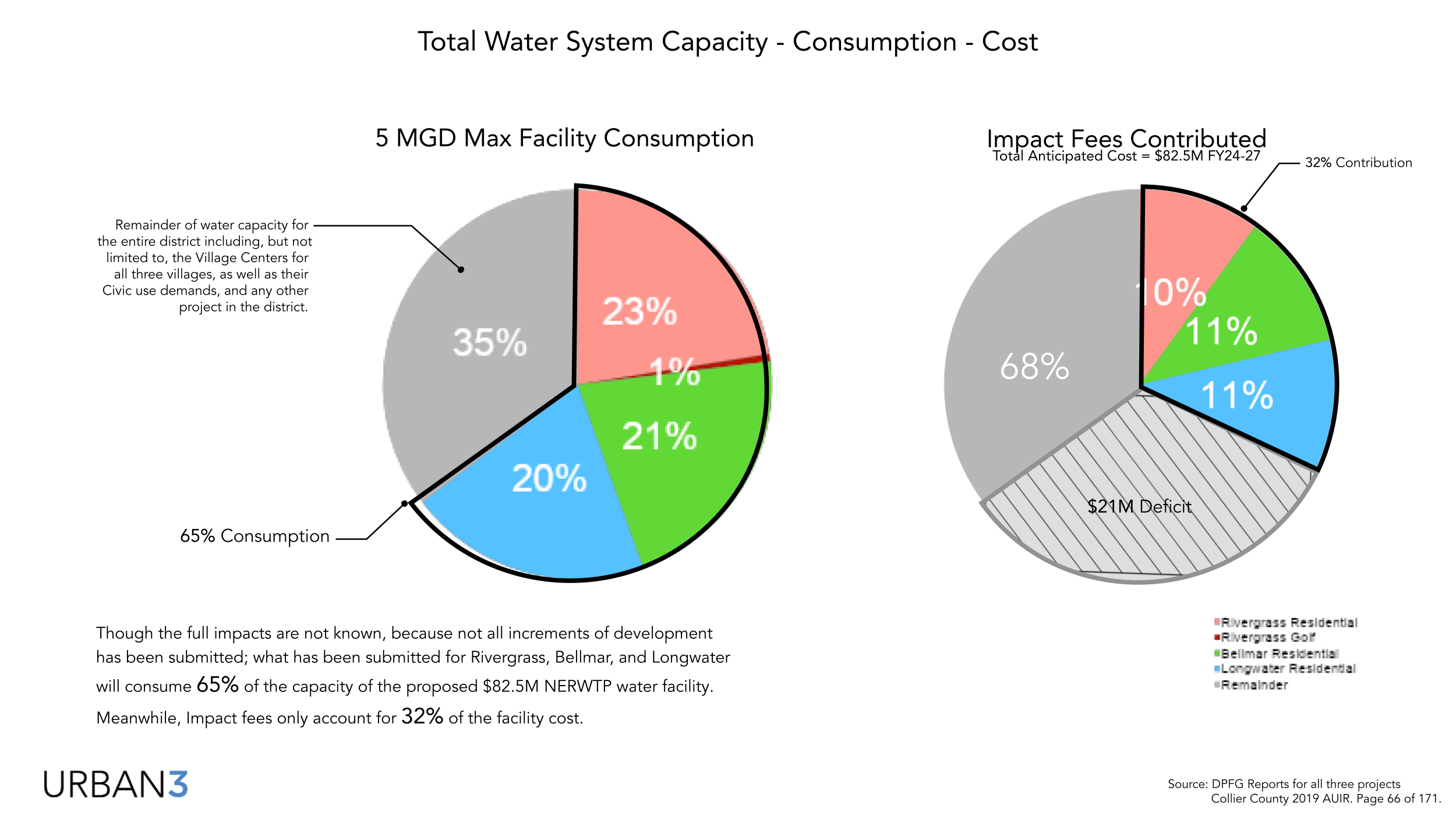

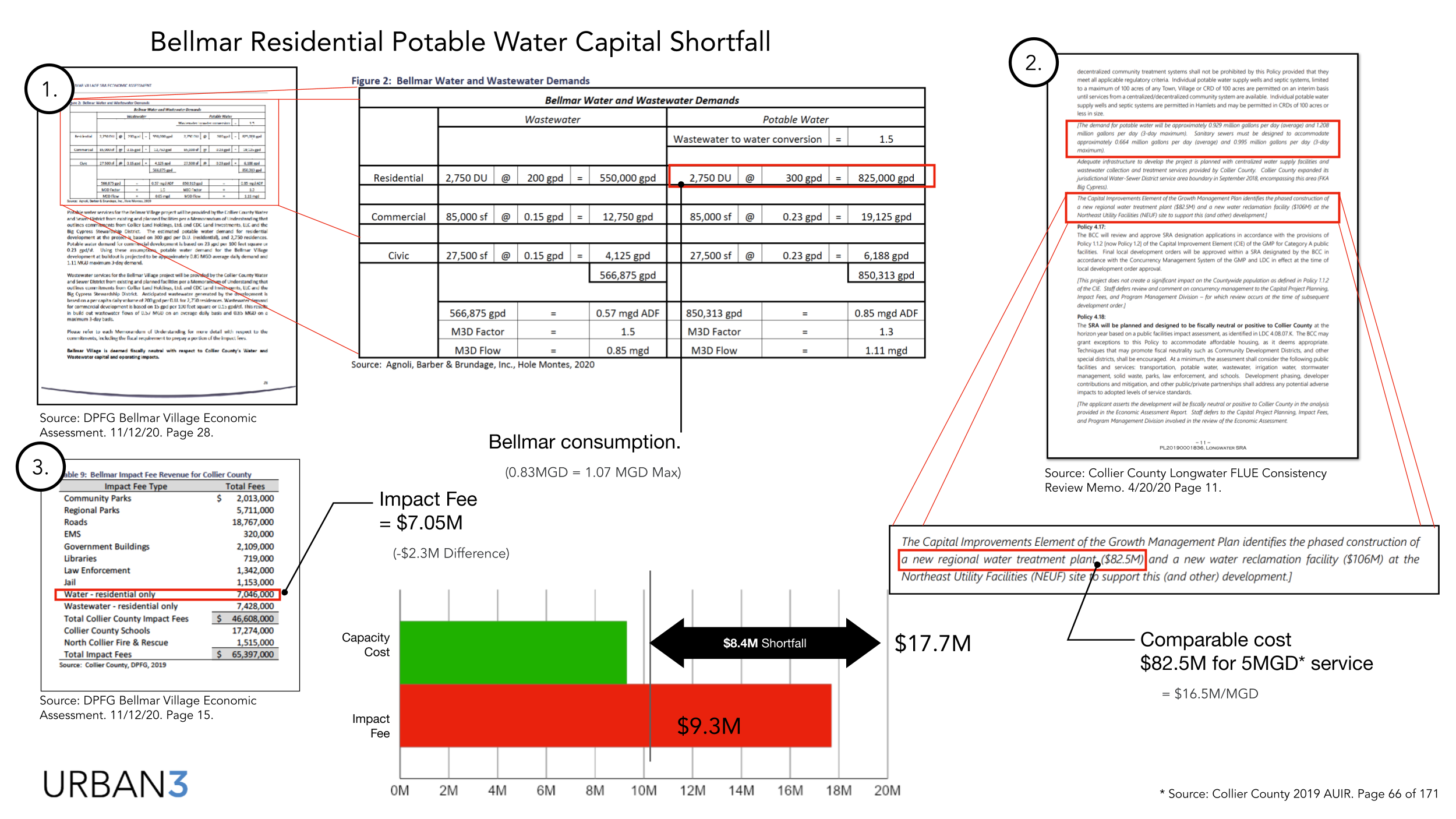

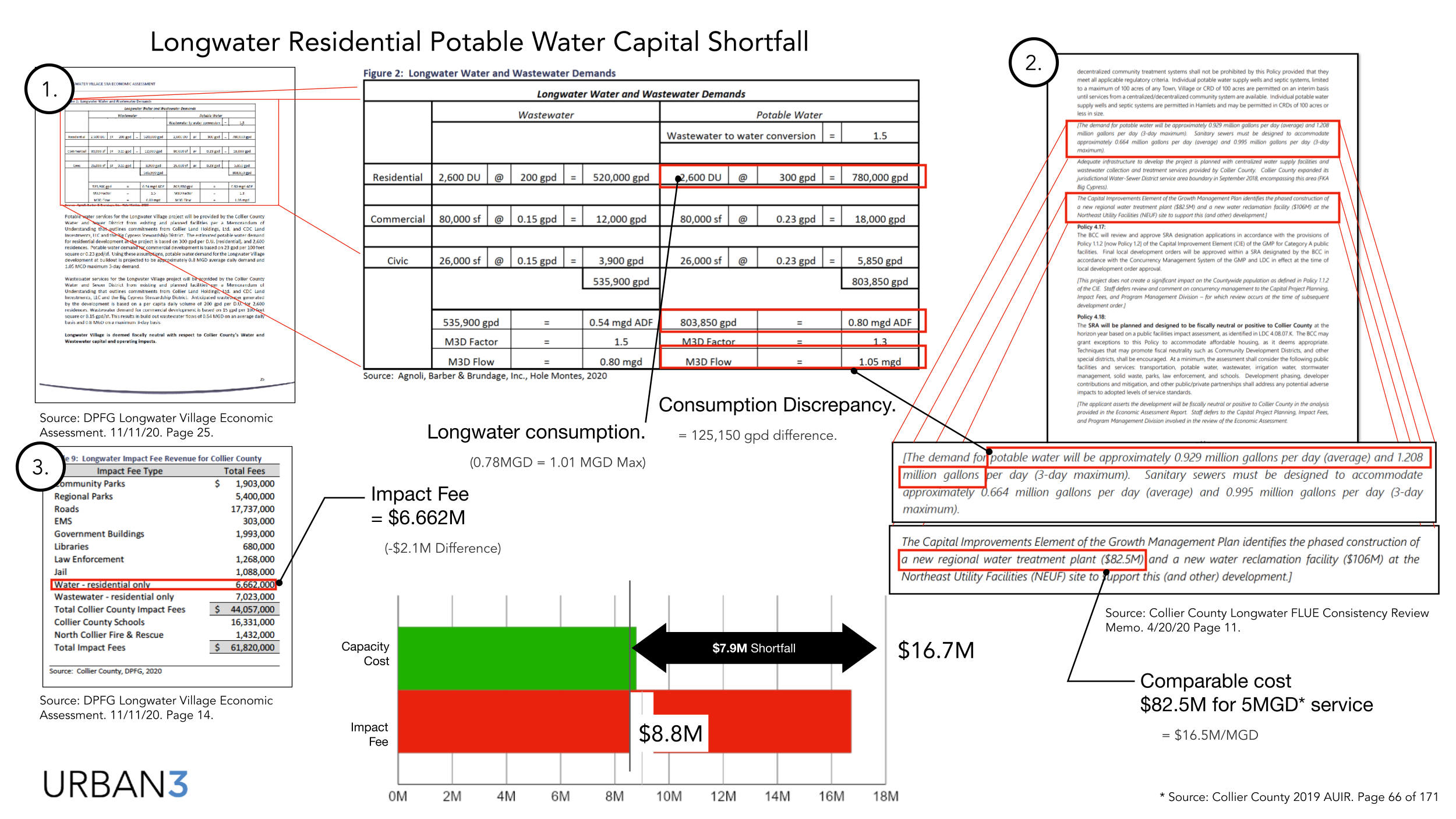

Using publicly available estimates, the geoanalytics consulting firm Urban3 conducted an assessment of the fiscal neutrality of the proposed villages. County documents and the Longwater project’s own consistency review memo indicated, as of mid-2020, projected costs of $106 million for the new wastewater facility, with a capacity of 4 million gallons per day (MGD), to be online by 2026. The potable water facility was estimated to cost $82.5 million, have a capacity of 5 MGD, and be online in 2027.

Based on these numbers, it’s possible to do a simple proportional-share analysis. The developer’s economic assessment includes projected daily water and wastewater demand from the three Collier Enterprises villages; that demand consumes 65% of each facility’s capacity. Yet the impact fees, which are supposed to cover capital costs incurred as a result of new development, only account for 25% of the wastewater facility’s cost and 32% of the potable water plant. The following slideshow from Urban3’s expert witness testimony illustrates the shortfalls:

Collier County has since contested Urban3’s estimates. In April 2021, utility staff came forth with an entirely different set of numbers than those readily available in public documents, suggesting that the project is much bigger and will be built in stages, with the costs heavily front-loaded. According to these new estimates, the water and wastewater plants will cost $141.6 million and $141.2 million, respectively, and have triple the capacity: 15 MGD for water, and 12 MGD for wastewater. These new cost estimates are wildly different from those previously reported for reasons that the county has not explained. The assumed construction cost per unit of capacity has shrunk by more than 50%. (For the wastewater, from $26.5 million per MGD to $11.77 million per MGD.) And the three proposed villages now comprise a much smaller share of the total capacity, with the rest presumably built to serve as-yet-hypothetical additional development well into the future.

Even if we assume that these previously undisclosed numbers reflect accurate projected costs, the county’s methodology reveals creative ways of fudging the numbers. Daily water usage fluctuates, so the facility must, by law, be built large enough to deliver the maximum anticipated daily capacity. Nonetheless, the county appears to show fiscal neutrality based on average capacity. The difference determines whether Longwater Village’s impact fees (and the others are in the same ballpark) leave it fiscally neutral or $5.8 million in the hole.

There are, quite simply, a thousand ways to fiddle with the numbers if you are so inclined. In 2020 the County quietly reduced the target Level of Service for water from 350 to 300 gallons per day per household. I have seen little record to suggest there was much public awareness of or discussion of this change, which may well be a warranted change: declining water consumption is a real, and welcome, trend across the United States. Regardless, it clearly has profound implications for planning and for evaluating how much new water capacity the new developments will use and should pay for.

Another knob that can be turned is the assumptions about household size that go into the model. If a developer can lowball their estimated household size, they can underestimate demand for utilities and save on impact fees. There is a large and arcane debate over what household sizes are appropriate for Collier County, which I will spare you—you can get an inkling of it here. At issue, essentially, is whether the population of a residential village 30 miles inland can be expected to be as seasonal as that of coastal Collier County, where vacation homes proliferate.

With this many squishy assumptions, you can get the result you want. The discourse of fiscal neutrality dominates Florida development politics, but it's very rare in the state for anything to be found not fiscally neutral. All this is doing the ratepayers, present and future, a huge disservice. A massive expansion of the region's water capacity, even as per capita demand seems likely to decline, deserves more rigorous scrutiny.

Pre-Committing to Growth

There’s one last point I'd like to make here, and it’s perhaps the most important one. Committing to a nearly $300 million northeast expansion gives the county a powerful incentive to double down on growth in this rural portion of the county, because once the facilities are in place they will need those new customers to keep the system, pun intended, afloat. The smaller the share of the facility cost paid by Collier Enterprises now, the greater the share that has to come from either future impact fees, or out of ratepayers’ monthly water bills.

This is why it's important that development itself happen in small increments—taking advantage of existing capacity wherever possible. This would prescribe compact infill in the western half of the county, not massive new development in the rural east. What Collier Enterprises has planned is the Growth Ponzi Scheme in action.

Cover image via Flickr.

Technocratic growth management in Florida has failed, and a new conversation is needed. Let's start that conversation now.