I had an old boss once who had a sign up in his office. It read, “Expecting people to be persuaded by the facts flies in the face of the facts.”

If you’re in the business of trying to change the world around you (for example, let’s say you’re a Strong Towns advocate in your local community), sooner or later you’ll need to be a persuasive communicator. Yet very few people, in my experience, are particularly deliberate about the process of persuasion, itself.

We all know on some level that there’s a big difference between being right and being convincing. Yet in practice, a lot of us are confident in the former but unstrategic about the latter. When we find that being right in a public forum is not enough to bring people around, we respond by trying to be right more forcefully, aggressively, or exasperatedly. Results are predictably poor.

This is a huge topic, one I can’t hope to do justice to in a single essay. But here are six rules about how people actually change their minds that should shape your efforts at persuasion—if, that is, persuasive communication is a priority for you.

That’s not a dig at those who don’t prioritize it. There are a lot of ways to be an effective advocate or change agent. Most of the work of changing the world isn’t about persuasion. A lot of it is about organizing. A lot of it is about rallying the troops: getting the already convinced to use their voice and their influence. A lot of it is about understanding power and ways of wielding it. There’s so much to advocacy that isn’t the art of changing minds.

But sooner or later, I’m sure there will be some important minds you’d like to see changed. Here are six principles for how you can work toward that.

1. People are persuaded by stories, not by facts.

Look, it’s not that facts don’t matter. If you want to make a serious argument to serious people, at some point you have to bring the goods. If you can’t, or if you are presenting demonstrably wrong information and are called on it, that will be discrediting.

However, we humans alive in the 2020s are awash in facts. We are drowning in facts. There are more facts available to us at the swipe of a finger than people could have imagined a mere 30 years ago, let alone at literally any other point in human history. We have far more access to information than our minds have any ability to make sense of it, to organize and catalog it.

We rely, more than ever, on narratives to tell us which facts matter, and how.

Think about how your senses work. When you hear sounds, the actual input arriving in your ears is a chaotic mess. But your brain can pick out patterns in the vibrations reaching your eardrums, patterns that past experience has taught it are relevant. Your visual cortex does something similar, turning raw data (photons) into a coherent story through organizing concepts developed through experience of the world—object permanence, perspective, light and shadow, the opacity of physical materials. We are largely not conscious of this process.

The way our minds do the same thing with information is through the power of narrative as an organizing device. And likewise, we are often only dimly conscious that we are actually doing this.

If I hand you a fact, you are going to search for a piece of mental scaffolding to hang that fact on, a story that it supports or challenges or simply relates to in some way. If you cannot readily find one, whatever I told you is going to be quickly forgotten. Not doubted, mind you: this isn’t really about whether we assume others’ factual claims are correct or incorrect. It’s about whether we receive them as significant. A lot of research confirms that we are far more apt to remember and make future use of facts that fit a pre-existing frame.

The most important narratives in any argument are not the ones explicitly laid out by the participants in the conversation. They are the ones that go unstated, but that provide the invisible scaffolding on which we hang the facts that seem important to know, that seem to provide some sort of significant guide to action or understanding.

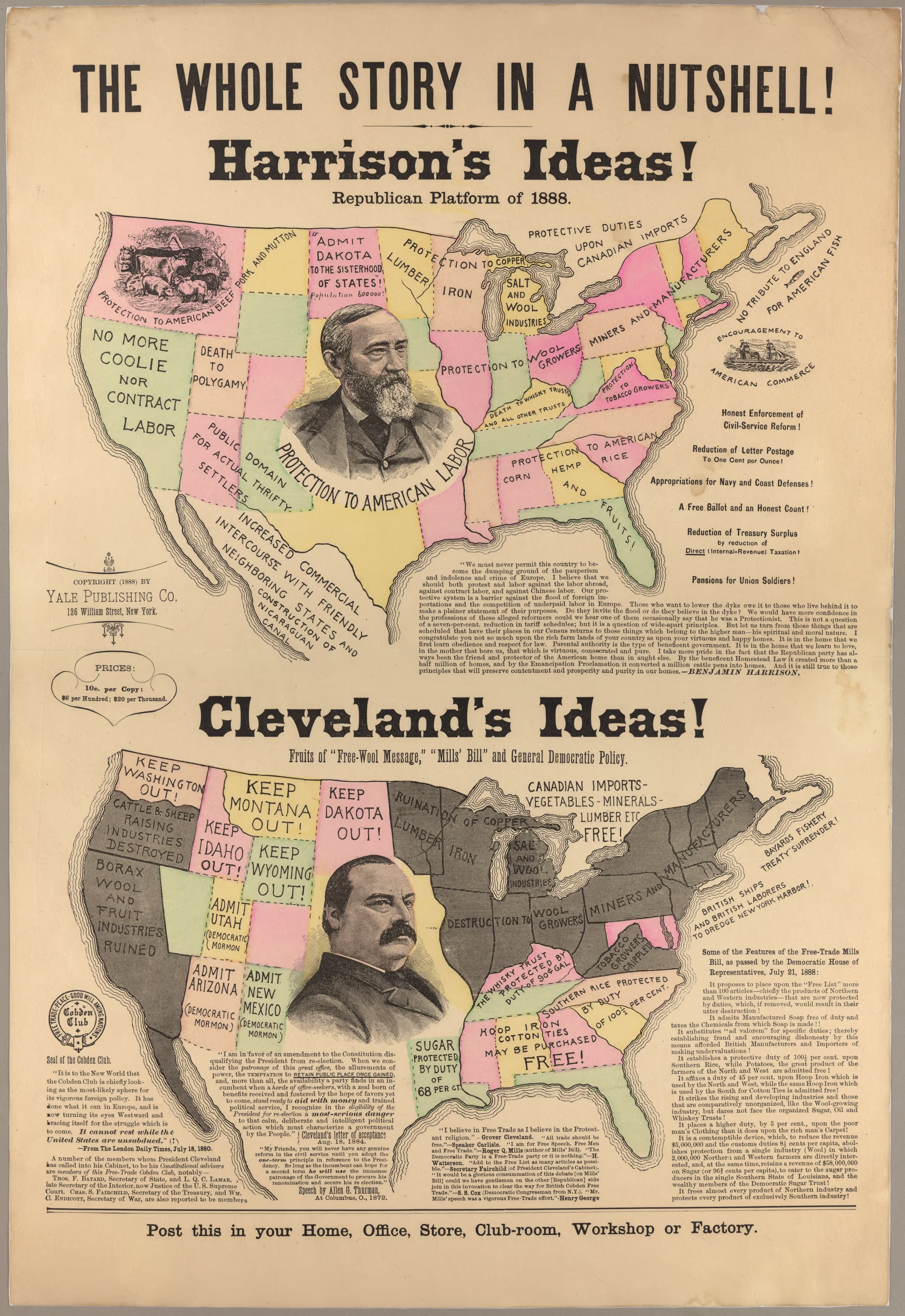

Invisible narratives always drive political discourse. One way to make this obvious is to examine the politics of a society removed in time and/or space from our own. Can you clearly discern the moral or ideological fault lines at work? Is it obvious to you who the good guys and bad guys were? Or do you have the same head-scratching reaction that I have to this campaign poster from the 1888 presidential contest between Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland? Here, folks, is the whole story in a nutshell! (Or presumably it would have read as such to someone already steeped in the key conflicts and narratives of the time.)

History suggests that our politics today will look a lot more like this unwieldy poster to observers another century and a half from now, and a lot less like a clear contest between the good guys and the bad guys than we might now flatter ourselves into thinking.

As a communicator, including outside the realm of simple partisan politics, you need to understand the invisible narratives that people draw on for meaning. Your audience will attach what you say to those narratives, whether you intend them to or not.

At Strong Towns, we have often used Jonathan Haidt’s Moral Foundations Theory as an internal guide to communicating across difference. Haidt identifies six moral foundations, around each of which you can construct narratives as to why these are important principles for the functioning of a good society. Some of the foundations, like Care or Fairness/Equality, resonate more in our present society with self-described liberals. Others, like Loyalty or Authority, resonate more with self-described conservatives. The scientific validity of Haidt’s framework has its challengers, but we are not interested for our purposes in whether it fully describes the way people arrive at moral intuitions. We are interested as communicators in whether it helps us tap into people’s moral intuitions to make a case for the things we advocate as urgent and important. And we find that it does.

As an advocate, always pay attention to the bigger story you’re telling about how the world is and ought to be. Not in one exchange, one instance of argumentation, but over time. If you are saying something that jives with people’s moral intuitions and they are receptively listening, then over repeated communications, your job is to build them a scaffolding on which to hang the things you wish to point out.

That scaffolding-building is central to our approach here at Strong Towns. If I tell you, for example, that 22% of the downtown of the average large American city is devoted to parking, and that statistic means something to you, it’s almost certainly because you slotted it into a story you know, perhaps one we’ve told here. We tell stories about what parking means: to our cities’ budgets, to walkability, to local vitality, to those trying to operate a small business or build affordable apartments. Those stories make sense (read: feel valid and significant) in the context of bigger stories, such as how excess parking is a reflection of the radical experiment we imposed upon our cities after World War II. And how that experiment has contributed to a slowly devastating mortgaging of American prosperity, which we must now find ways to rebuild.

2. The spread of beliefs is a social process, not an individual one.

Ideas spread within networks. You are much more likely to take an idea seriously once you have seen it repeated many times by people you know and like, or by thought leaders whose values you perceive as in alignment with your own.

A lot of smart people chafe at this idea, because we like to think of ourselves as dispassionate judges of the evidence in front of us, both from our own lived experience and from what we read and watch. And indeed, those who think of themselves as evidence-minded and well-read might lean more heavily on information presented to us with citations, with data points, with appeals to academic or scientific authority.

But we’re still almost certainly pre-screening that information. Lots of ideas floating out in the world come with the veneer of credible authority but are, upon inspection, flimsy. None of us have time to inspect it all, outside of maybe a narrow area of deep personal expertise. So how do we pre-screen? Most of the time, we are far more likely to examine an idea closely and take it seriously if it comes pre-approved by people we find credible.

This means that if you can get a large group of people who find each other credible repeating an idea, it will be quickly and repeatedly reinforced, and this process won’t have all that much to do with the solidity of its basis in fact. There is a recursive element to this, something that savvy marketers (of products, services, ideas, and ideologies alike) absolutely know how to tap into. Ben Hunt of Epsilon Theory, one of the smartest observers of how narratives spread in contemporary America, talks about the power of “the crowd watching the crowd.” Very often, the power of an idea comes simply from the fact that we believe lots of other people believe it. Our sense of which topics or debates or conflicts are important to talk about is mostly driven by what we believe lots of other people are talking about.

And again, a lot of this is not about which ideas we judge to be correct, it’s about which ideas we judge to be important—in a world in which information is far too plentiful and we need filtering mechanisms. “What do the people in my social circles, or who share my political values, seem to be focused on?” is a reasonable heuristic on its face. But in a world of massive information, it’s also one that can be gamed.

3. Our minds are changed by trusted messengers.

Ideas spread within networks, but certain people or information sources within those networks have vastly disproportionate influence. They’re the ones who are pre-screening ideas and information for many others within a like-minded community.

Think of two concentric circles. Circle A, the larger one, consists of those sources you rely on to help form your opinions on issues where they are not yet fully formed. It will consist somewhat of people you know personally, but probably also a lot of trusted publications and institutions. The specific author of an article might be someone you know nothing about, but if the publication is one you find trustworthy and compelling, and (this part is essential) the substance of what you’re reading aligns with narratives you already buy into, you are likely to find it persuasive.

There is likely a very small circle of people who are actually capable of challenging your core narratives, or changing a well-formed belief you already hold. This is Circle B. Think about the people in your life whose opinions you respect enough that if they said something you firmly disagreed with, it would cause you not to dismiss or try to rebut their view but rather to question your own priors and humbly concede, “Well, maybe there’s something I should understand better.”

In local politics, the realm in which most Strong Towns advocates are operating, Circles A and especially B are tremendously important. The key is to reach the people who play this role for those in positions of influence: the community’s trusted messengers.

Sometimes in the local realm you ultimately have an audience of one: a city council member, for example, who is the swing vote on a key project or policy. If that’s the case, you are far better off investing your energy in figuring out who they listen to, and working on influencing those messengers or at least getting their co-sign for what you have to say. That might mean certain local media sources or personalities. It might mean longtime activists who have the ear of politicians. It might mean groups like the Chamber of Commerce. The key is to observe, and figure this out.

You can write the best email to your mayor; you can relentlessly make strong, well-supported arguments in a community Facebook group; you can show up at the public meeting with the most rock-solid, well-rehearsed three-minute testimony. All of it is very unlikely to matter if you are a relative nobody to your audience. You will achieve nothing. Find the people who are the trusted messengers, and work to move them.

4. Nobody trusts a jerk (except the jerk who’s already on their side).

“You yelled at me and called me an idiot in front of an audience of your jeering friends. I now see the error of my ways,” said no one ever.

We all know this, right? Nobody’s mind is changed by hostility. Nobody’s mind is changed by shame and moral opprobrium from strangers. Nobody’s mind is changed by being the target of snark and ridicule. It’s the people whom you can reasonably think of as on your side in some meaningful way who will get through to you about the thing on which you’re not (yet) on theirs.

Once you’ve lost this, it’s hard to get back. Credibility, to borrow a cliché that applies to many things, is a staircase going up and an elevator going down.

I've seen my writing, as well as the general voice of Strong Towns, described as “temperamentally conservative,” and I guess that's true. I don't think it's the only way to be honest and fair. It's a mode that I am comfortable with, but you can be honest and fair while also being provocative, even shocking. You can be honest and fair while calling out bad ideas, bad policies, hypocrisy or harm, and making the gatekeepers of those things uncomfortable.

Say things that are true. Write a sentence, step back from it. Read it. Ask, “Is this true?” If the answer isn’t an unequivocal yes, revise or scrap it.

Characterize the views of your opponents in terms that they themselves would accept. Ask yourself how you know you’re doing this. If you’re not sure, talk less and listen more until you are.

A lot of people on social media go into high-school-debater mode. They employ an aggressive, antagonistic rhetorical style aimed at winning the argument and making someone else lose it. Often, mockery is part of this—the art of the dunk. The rationale is usually, “My audience isn’t the person I’m arguing with. They can’t be convinced. My audience is the third-party onlooker who will see that I’m right.”

But even that onlooker sees you kind of being a jerk.

Remember that people experience online spaces as “their” space—in the algorithmically curated world of social media in 2024, you are always on their turf from their perspective. You’re the one barging into someone’s feed and being a jerk. (And you’re mad because they’re on your feed being wrong!)

I’m deeply skeptical that this does more than rally the troops, eliciting high-fives from those who already agree with you. Rallying the troops can be a good organizing tactic, mind you. It’s just not a good persuasion tactic.

5. Our fundamental beliefs are changed bit by bit, not all at once.

There are a handful of big-picture issues—narratives about the world and about politics—on which I completely disagree with my own views that I held 15 years ago. Two things strike me about this:

One, I was largely unaware of these beliefs changing as it was happening. There were no sudden epiphanies. Rather, what happened was something like replacing the wood in a ship board by board, until not a single plank is original. At any given point in time, the ship you’re sailing today feels like the ship you were sailing yesterday.

Two, if I had an argument with my 15-years-ago self about one of these topics, I am confident that I would fail to win it. In fact, then-me would think now-me was hopelessly dense, and vice versa.

An incisive argument or observation, planted at the right time (with at least the co-sign of the right trusted messenger), can seed some nagging doubt about a narrative it clashes with. Then that doubt has to take root.

It’s pretty easy to get someone to go from “X is absolutely right” to “X is basically right with some caveats”—that doesn’t introduce much cognitive dissonance. It doesn’t threaten your standing in a group that is centered around acceptance of X. It actually makes you feel like a smart, independent thinker. It’s also the first step toward actually rejecting X, if X is, in fact, wrong.

Play the long game.

6. Social consensus is less solid than it seems.

When you see a narrative you think is wrong circulating within a community, the vast majority of people who are reiterating some part of that narrative are not unmovable true believers. Most are simply repeating something that is broadly affirmed within those circles, to which they are moderately committed at best. They are part of the crowd watching the crowd.

This is the dynamic, for example, of most of the “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) attitudes that can appear suffocatingly dominant in local politics and community discourse. I know the demoralizing experience of envisioning something positive for my neighborhood, and then reading a Nextdoor thread of person after person dumping on that idea in a chorus of misguided fear and stubborn refusal to envision anything in the community changing for the better.

What appears to be a monolithic consensus often isn’t: rather, it’s a handful of loud voices in a feedback loop with each other, and many others who fall somewhere between passive mild agreement and choosing to just stay quiet.

Arguing directly with the loudest and most demagogic participants in such a community—and thus with the apparent social consensus—doesn’t work very well. So what does? How do you start to shift that social consensus if you think that there's a whole community that has got something basically wrong?

You start to crack open some doors. Point out things that aren't at 180-degree odds with the majority view, but that complicate it or introduce nuance. Point out a perspective that isn't usually heard (those of renters in a conversation dominated by homeowners; those of people who walk or use wheelchairs or strollers in a conversation dominated by drivers). Don’t be preachy or obnoxious about it. Don’t act like you’re trying to win a debate. Do it with an awareness of the core narratives of the space you’re in. Do it in a way that one or two of the group’s trusted messengers—those who are prominent voices but also appear amenable to nuance and disagreement—will hear you as a basically friendly countervailing voice.

And this does a couple things for people observing these interactions who aren't deeply committed to that loudest narrative—which, again, is probably more of them than it seems like. Maybe they had doubts, but they didn’t hear anyone else really validating those doubts. A little bit of validation can fracture what once appeared to be a monolithic consensus. This is where you get to be transformative, not by winning the argument with a mic drop, but by steadily planting seeds.