When Yuppies Are No Longer Urban

This story was originally published on Diana Lind’s Substack, The New Urban Order. It is shared here with permission. Images were provided by the writer.

Alison Roman’s Catskills store.

I was reading a post on Substack when I found out (a year late) that Alison Roman had opened a general store in the Catskills. For those of you who have never heard of Roman, she is one of those recipe writers turned food influencers whose #thecookies once broke the internet and still maintains a 5.0 rating after nearly 14,000 reviews. Roman’s decision to launch her first retail endeavor outside the city made a certain kind of sense - yuppies, which once stood for “young urban professionals” are increasingly moving away from urban places to small towns, resort communities, and going rural.

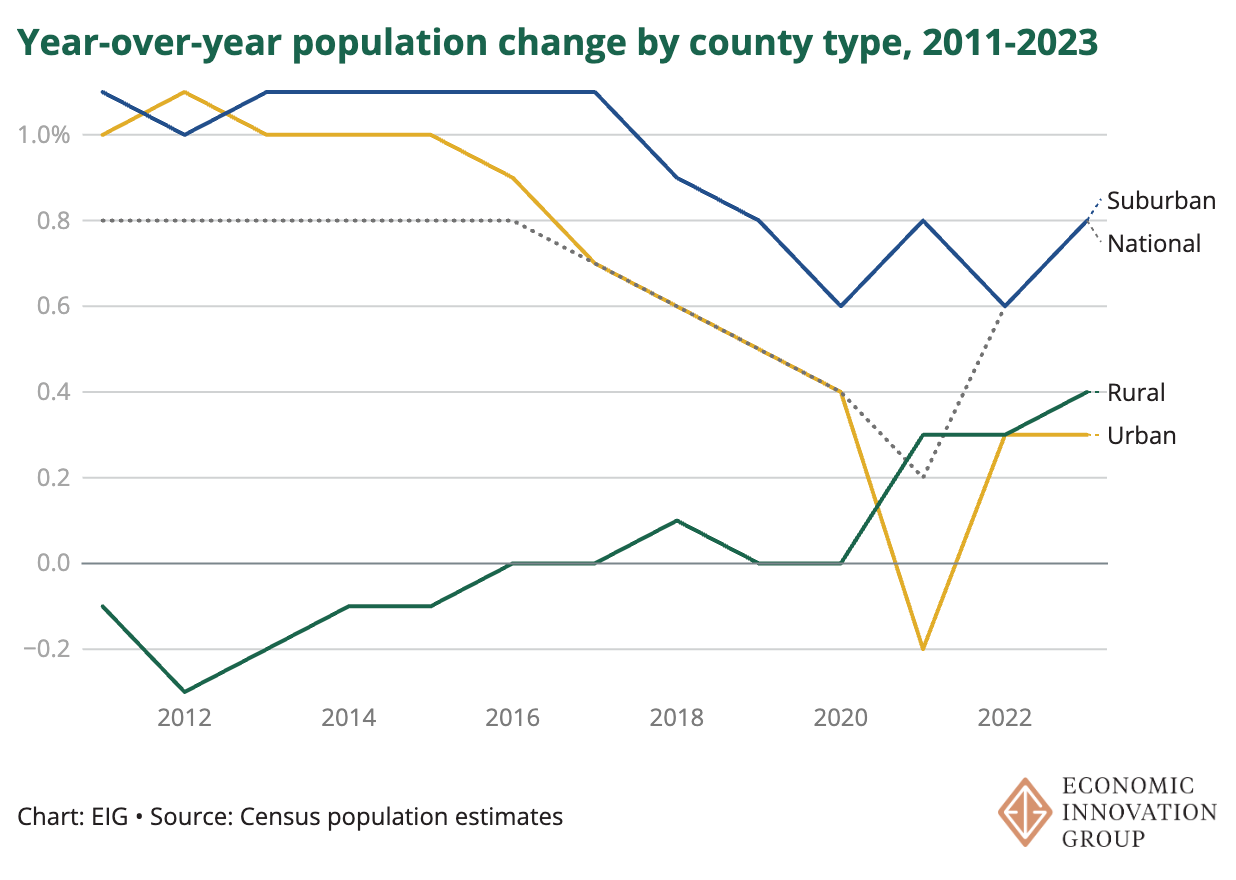

Small communities like the towns that dot the Catskills have seen much growth over the past five years. According to University of Virginia researcher Hamilton Lombard:

Since 2020, two-thirds of growth in the 25 to 44 population has occurred in metro areas with fewer than one million residents or in rural counties, a stark contrast to the last decade, when 90 percent of this growth was concentrated in the largest metro areas with over four million residents.

And newcomers to these areas are often more affluent than old timers, as seen by rising housing prices, and in some cases, genuine income growth.

Just as younger adults have increasingly migrated to rural counties with high natural amenities, the incomes of new residents in these areas have risen sharply since the pandemic. IRS data from 2021 and 2022 shows that in counties with the highest natural amenity scores, incomes of new residents have grown three times faster than the national average since 2018 and 2019.

Why is this happening? Housing prices explain part of it. Cities that once attracted upwardly mobile professionals have become too expensive even for yuppies themselves to live in.

And COVID gave small towns near big cities a boost. Many affluent people in dense cities escaped to places like upstate New York, Cascadia, coastal New England, and rural Virginia during the pandemic, liked it, and never returned.

Yuppies are also a demographic most likely to have remote work jobs and can take their big city salaries, networks, and real estate profits to a much less expensive community. This lifestyle arbitrage has significant downsides for the people already living in these small towns.

Why should we care? We are soon entering a period of zero-sum population moves, where each locale’s gain is another place’s loss, and these moves have consequences for many of the great cities of the 20th century. But we may also be witnessing the decline of one of the most recognizable demographic trends of the past 50 years – the alliance between yuppies and cities.

Aaron Renn recently wrote about the important societal distinction between the middle class and the striver class in understanding the United States. And though he doesn’t explicitly say it, he implied the middle class lives in the suburbs and the striver class lives in cities:

Being middle class is about building a life. It's primarily about the material elements of the American Dream: a house with a backyard for grilling in a nice neighborhood, a car, family vacations, retirement savings, a social life with friends and neighbors and people from church, children who are able to build a life with even better material success.

Being striver class is about the desire to move up in the world. There are material aspects to that, but also the key element of social status. The striver wants to get into the right schools, to move to the right city or neighborhood, to vacation in the right destinations, to have intellectual or artistic ambitions, to run in the right circles, to be recognized and accepted by people at higher social levels.

Yuppies defined the striver class and built cities in their image. But what happens when the strivers don’t want to live in cities anymore?

As Tom McGrath wrote in his 2024 book, The Triumph of the Yuppies, in the 1980s young, educated people flocked to cities in part to differentiate themselves from the stultifying suburbs they grew up in. If suburbs were places where women’s professional dreams went to die, where men spent their weekends mowing lawns, and where life revolved around children, yuppies sought out cities where women and men were equals and they were equally ambitious about everything from their careers to food to real estate and more.

Nowadays, young professionals are promoting a different vision of the good life. It’s a vision that is still obsessed with high-quality experiences whether food, architecture or a hike. And still dismissive of the suburbs, with their conformity and basic-ness. (Beautiful small towns like Nantucket or Hudson have the high-minded aesthetics that have always engaged yuppies, whereas can you imagine Alison Roman launching a general store from Great Neck or Tenafly?)

But it also seems to fetishize a much smaller life — one where the ambitions of moving up in the world, or having a world-scale impact, are now out of the picture. Masters of the Universe in 2025? Definitely not.

In this way, the striver and middle class seem now to be converging around a vision of life where caring about and mattering to a small community of friends and family is as important as moving up in the world. Especially at a time when many career paths are imploding and AI is about to take all our jobs, this makes sense.

And there’s no doubt many of these smaller communities offer the joys of natural amenities and the unhurried and uncrowded pace of small town life. And having big impact in a small community can be more satisfying than small impacts in a big city.

But this trend also marks a diversion from the ambitiousness of 20th century urban life. Yes, yuppies prioritized fancy restaurants and upscale clothes, but these products seemed symbolic of grander goals: of building big things, of generating make-it-new culture that trickles down into mainstream society, of intersecting with an ever-shifting cast of diverse characters, of maybe one day improving the lives of many.

I was working on this piece while on an Amtrak that passed through Baltimore. I happened to see a long line of about 100 people outside an abandoned warehouse. I then realized that they were waiting for free food handouts. I wondered: as young professionals reject cities, are we quiet quitting more than just the rat race but also caring about the greater good?

Small Cities, Big Problems

My sense is that this shifting demographic will turn out better for cities than small communities. Cities could definitely stand to lose a few yuppies! But as these smaller communities receive wealthier new residents, they will have to contend with some big city woes.

A 2020 study on rural life notes, “Over the past 50 years, OMB has reclassified 753 counties—nearly 25 percent of all counties—from nonmetropolitan to metropolitan.” Much of rural America inevitably becomes metropolitan (having more than 50,000 residents) at some point — that’s how these areas survive.

Nonmetropolitan counties that have transitioned to metropolitan status typically include higher percentages of college-educated people, higher per capita incomes, lower poverty rates, and lower percentages of older people. Over time, the net transfer of education and income reflected in this transition has exacerbated rural-urban disparities in human capital as well as population, adding to the narrative of rural decline.

Kingston, New York

In Kingston, New York, Steve Noble, the 30-something mayor who grew up in the city, has been fighting to enable some of the most progressive zoning in the state. With its beautiful historic architecture and dense landscape, the town could take advantage of this new zoning to grow its economy and address rising housing prices. But Kingston has been dogged by a deal gone awry with a Manhattan developer who has been relentlessly suing the city, keeping part of Kingston vacant.

Noble went so far as to publish an open letter in the local newspaper urging people to write to the developer to drop his lawsuits. Noble included the developer’s address on West 12th Street — fittingly, a neighborhood that yuppies turned from literal meatpacking businesses into haute retail over the past 30 years.

When I searched for the address, Google showed me a 2015 New York Times article (“In the West Village, Modern Boutique Owners Who Live Where They Work”) about a yuppie couple who opened a boutique on that same block. I clicked on the article’s link to the modern boutique’s website, but got an error. Turns out the couple who ran the boutique no longer lives in Manhattan, but in a 2,000-person town in Eastern Long Island instead.

Diana Lind is an urban policy specialist and writer. She is the founder of The New Urban Order, a Substack about the future of cities, and a visiting fellow at the Johns Hopkins SNF Agora Institute's Center for Economy and Society. Her book, “Brave New Home: Our Future in Smarter, Simpler, Happier Housing,” explores the social, economic, and environmental consequences of single-family housing in the U.S.