It is with deep sorrow that, at the request of Leon’s wife Irene, I pass on the following message:

Leon Krier died Tuesday 17th of June in Palma de Mallorca, with the same quiet courage with which he lived his life. He was a craftsman, the son of a tailor and a pianist, who distilled the beauty of the cities and buildings he saw into their essential attributes and used the same cloth to imagine and reimagine places for people to live together. He was gentle but uncompromising in everything he did, preferring to withdraw than be drawn into political skirmishes, inhuman bureaucracy or pollute his designs. He created beauty with his hands every day: in his drawings, the beautiful piano music he played, the fruit he carefully prepared every morning for his beloved wife. He suffered viscerally for those in hardship and was disillusioned with the course of the world. Without ego or fear of voicing unpopular ideas, he remained unwaveringly true to his ideals of beauty, community and friendship. Leon is survived by Irene, his friend and wife of five decades he always adored, his stepdaughters, son-in-law and granddaughters, his sister Marthy, her husband and their children and countless friends and colleagues around the world whose lives he profoundly touched.

This week, I was saddened to learn of the passing of Leon Krier. I’m not overstating it when I say his influence on my professional journey was profound.

My passion for architecture is rooted in the vacations of my youth, when my family would wander through the historical towns of the eastern United States. I was captivated by these places: brick homes, boxwood-lined walkways, and grand porches and arcades. The architectural features of these historical buildings seemed to tell a story with every detail.

While other children may have groaned during historical walking tours, I absorbed them. I wanted to design buildings like those. I wanted to contribute to the long and rich history of these places that celebrated tradition and humanity. But when I reached high school in the late 1990s and began looking at architecture schools, it did not take very long to realize how out of step my desire for traditional architecture was with the prevailing orthodoxy of the architectural academy. Architectural education had largely abandoned traditional patterns. Glass boxes, stark modernism, and “innovation for innovation’s sake” dominated the curriculum.

None of that resonated with me.

In my search for a place where I could learn more about these traditional patterns, I discovered the University of Miami School of Architecture, which at the time was one of the very few schools in the country embracing traditional architecture. Despite skepticism from my family, I traveled across the country to study and advance my passion for traditional architecture.

Prior to the start of the semester, the school sent out a required reading list that included Jane Jacobs’ "The Death and Life of Great American Cities." That required reading set the tone for what would become a transformative education, not just in buildings but also in urbanism.

Just a few weeks into the semester, we were asked to attend a symposium on traditional architecture at the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables. As freshmen architecture students, we were ushered up to a balcony where we sat on the floor, barely knowing what we were about to experience.

The first speaker was Andrés Duany, who spoke of the New Urbanism movement and the struggle to build traditionally patterned communities in the modern era. Then he introduced the keynote guest: Leon Krier.

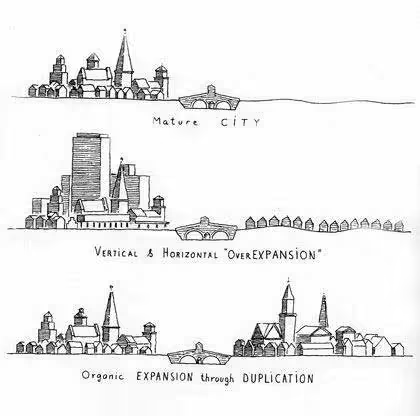

I didn’t know who Krier was at the time. But when he took the stage, he started sharing slides of sketches from his latest book that had just been submitted to his publisher. I was completely spellbound. His presentation, accompanied by his simple, eloquent sketches, revealed not only how far contemporary cities had strayed from traditional urbanism, but also why that mattered so deeply. He spoke of Poundbury, his masterwork in England, and the idea that cities should reflect our humanity, not abstract theory. He talked about cities as living places that change and adapt over time.

He posed the question, "Are our cities a result of choice or fate?"

This continues to be a very radical idea—that we can choose to build coherent, human-scaled cities and towns, or we can allow ourselves to drift toward a dystopian future of fragmented, unsustainable, and alienating development.

That day, I realized I didn’t just want to design beautiful buildings. I wanted to understand how those buildings lived in a neighborhood, how streets supported human life, and how design could make people feel rooted, seen, and connected.

Krier provided me with a call to action. From that moment forward, Krier’s influence ran through every sketch I drew. His hand-drawn illustrations, simple yet deeply expressive, became a model for how I would communicate ideas in my own work. If you look through my student projects and portfolio, you’ll see the influence of Krier, not just in my drawing technique but also in the type of work I was doing.

That symposium altered the trajectory of my career. It led me to pursue a graduate degree in urbanism and guided me toward working with cities and communities across North America. I became a restless urbanist, exploring and pursuing places people love.

Krier helped me realize that I didn’t want to draw mansions or create iconic one-off buildings. I wanted to work at the intersection of design and civic life. I wanted to contribute to the creation of places that dignify the human experience.

What makes Leon Krier so remarkable is that he stood firm when traditional architecture had been exiled from academic and professional circles. He wrote when few wanted to hear it or acknowledge it. He was dismissed as backward or regressive. Yet he never wavered. He never gave up his belief that the patterns of the past weren’t obsolete, He reminded us all that these patterns were vital, humane, and deeply wise.

I also appreciated that he wasn’t afraid to walk away from projects that betrayed his principles. He stayed above the fray of politics and institutional approval, choosing instead to focus on projects he believed in, that embodied the values he cherished.

Leon Krier leaves behind more than sketches, books, lectures, and plans of built and unbuilt work. He leaves behind a generation of designers, planners, and urbanists like me, who see the world differently because of him. He rekindled an appreciation for tradition, for place, and for the quiet dignity of well-loved streets and homes.

His ideas, once radical and now increasingly accepted, will live on. I owe him more than I can put into words.