St. Francis Church in Brainerd, Minnesota, is my parish.

That’s putting it lightly. It’s not just where I attend Mass. It’s where I was baptized, where I got married, and where I now take my family. It’s the church where I used to sit next to my great-grandparents, where my grandfather’s name is on a plaque in the back for serving in World War II, and where—when I was a broke high school student—I chipped in more than I had to help buy the organ they still play today.

My mom used to teach at the parish's Catholic school. A lot of my friends went there. Today, a lot of my friends send their kids there.

I live in the neighborhood just up the street. My office is next door, so every day I walk past the church on my way to work and back again. I’m a routine guy; each night I take my dog for a walk, and every walk takes me past St. Francis.

I’m a Catholic—broken and messy, to use secular terms (Catholics would just say “sinner”)—and I want to be better at all of it. At practicing my faith. At being a husband, father, friend, and neighbor. At being a human being.

My love and commitment to all of it isn’t passive or halfhearted. I’ve chosen to live here, in this place, in this neighborhood, in this parish, among these people.

Today, I’m hurting, and I want to say why. First, the backstory:

The local school district recently finished a major capital project that "upgraded" four of our neighborhood schools while tearing down a fifth (to expand parking). The upgrades included buying up and tearing down homes around the schools so each school could be made more campus-like. More parking, faster in and out of the neighborhood, stormwater ponds, and other suburban design elements. I fought against this—not against the concept, I do want to invest in schools, but the way we went about it. I lost every battle. It cost me many sleepless nights and, sadly, even some friendships.

Part of why I lost was that the school district is huge and most people drive into the neighborhood schools. This especially includes the teachers, administrators, and project designers, a tiny fraction of whom live in the neighborhoods they work in. It was very easy for them, and for the voters in this massive area, to think in their terms: How can I get into and out of the neighborhood as quickly and efficiently as possible?

These changes were done to the city, not with the city. I was on the planning commission at the time, and there was a lot of frustration in city hall about the loss of homes, the loss of tax base, and the general degradation of our core neighborhoods. This is especially true as it was done under the threat of "If you don't do this, we'll close the schools and build new ones out of town."

By the time it was over, we'd not only had extended conversations and meetings on this, but that work had also resulted in a whole new set of codes and regulations designed to limit the ability of anyone to do this to us again. We all seemed more united around a vision that would elevate our care for Brainerd and accommodate (generously) people who commuted here, reversing a policy that had long prioritized commuters from other cities and made the experience of residents an afterthought.

That’s the backstory. It’s a pretty common one I’ve seen play out time and again around the country.

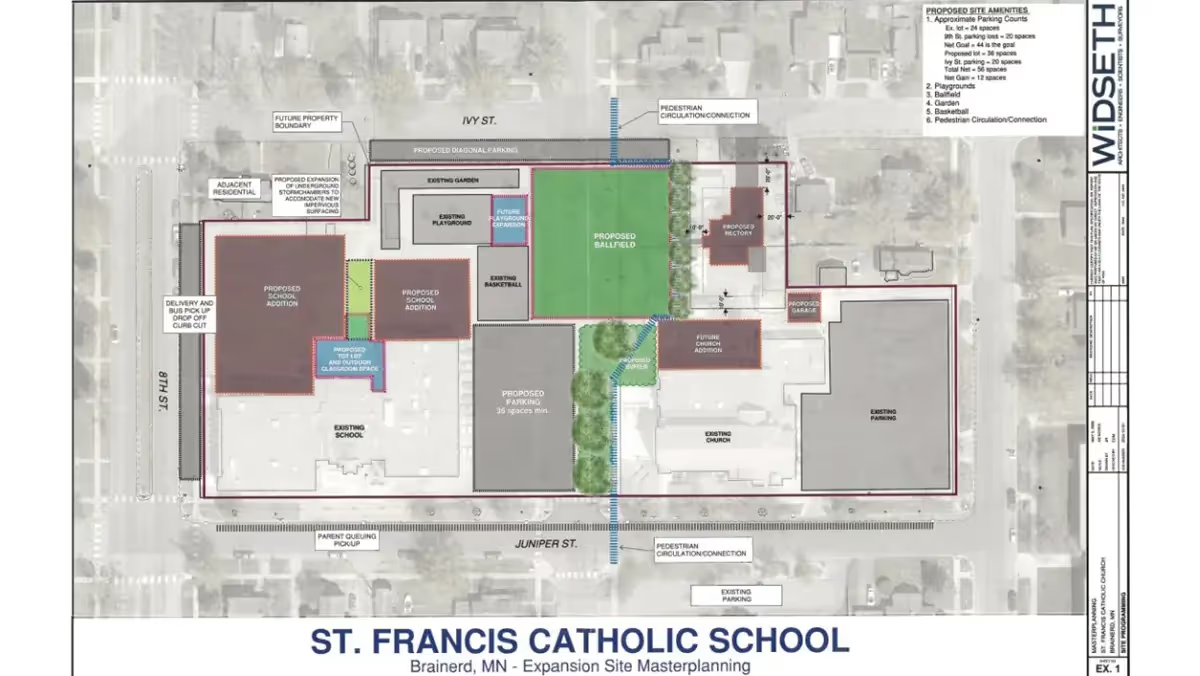

Now, my church, led by a parish council of people who generally don't live in the neighborhood and advised by the same consultants who led the school project, developed a similar plan. Buy homes, tear them down, expand parking, vacate a street, and create an enclosed campus where the neighborhood is an interface to be managed, not a community to be embraced.

I told our church leaders that things had changed at city hall. That this plan would not be well received. That it had almost no chance of being approved. That we should pause, rethink, and come up with a new approach that meets their goals in a neighborhood-friendly way (which isn’t all that hard to do, let’s be clear).

Well, it just got approved. All of it.

Part of my writing is working through the anger phase so I can get to the heartbreak on the way to acceptance. I have a ways to go.

I’m frustrated with my fellow parishioners. Being Catholic means submitting to the Church’s teaching. And there are plenty of things in that teaching that my rational mind struggles with, things I don’t fully understand, things I’ve had to accept as mystery. That’s part of the practice. It’s a discipline of humility. And in that humility, I’ve found understanding. I’m deeply grateful for my faith.

But submitting to the teaching is not the same as submitting, full stop.

When the parish was asked—through a survey—what our priorities should be, one answer came through loud and clear: parking. More of it. More convenience. More efficiency. This was not just making a wish list for someone else to fulfill. The people next to me in the pews are more than willing to pay for more parking.

I could give my own sermon here—on what Christ said about comfort (not much) and what He said about sacrifice (quite a lot)—but that’s not my role. That’s someone else’s role. And I’m frustrated that it wasn’t filled. That in a parish called to carry so much, the thing we consistently choose to carry with our greatest allocation of resources is our own transactional convenience. That feels, at best, uninspired. At worst, it feels misdirected.

I’m frustrated with the parish council. These are good people, just like the school board was. But they live in their own experience. They didn’t pause to understand the neighborhood, let alone immerse themselves in it. When they spoke—at meetings, in testimony—they described a neighborhood I don’t recognize: dangerous, unfriendly, high-traffic, unpleasant. They talked about the church as an oasis surrounded by hardship. That’s not true, but to the extent that we believe it, we never seem to stop and ponder our role in it. I live here, but they largely don’t. So they share a kind of group fiction, reinforced by distance and repetition.

I’m really mad at the city staff. They are consistently some of the most incompetent professionals I’ve interacted with. There is no core vision; part of that is the council’s fault, but staff does little to help build one, let alone reinforce it. They seem to give poor advice because they’re afraid to give clear advice. They pass along approvals with templated conditions, lifted from other reports. There’s no discernment. No confidence. No memory.

Their recommendation to vacate the street—to literally give away public right-of-way—was malpractice. It ignored state guidance, the League of Minnesota Cities, and basic standards of planning. It reduced safety, reduced connectivity, made utility access more difficult, and provided zero public benefit. But the staff signed off. No problem. As if public streets are expendable. As if urban design in a gridded neighborhood is an annoyance to them. Or worse.

We might be better off with no staff than with this staff. At least then our elected officials wouldn’t have to start every conversation in a hole of professional dysfunction they’re forced to mentally dig their way out of.

And I’m mad at our city council. All but one voted in favor. One “yes” vote councilor cited the precedent of the school district, as if the years of discussion, reform, and new ordinances in between that disaster and this application never happened. Others pointed to the number of people in the room, making public attendance a proxy for public benefit and not seeming to recognize that the sheer volume of Catholics my church could round up (there are over a billion of us, after all) shouldn’t override a vision they’ve spent years articulating.

I’m a whole lot of angry at a whole lot of people, but I’m mostly mad at myself.

Let’s be clear: I’m not on the parish council. I’ve never volunteered. I never even considered it as my role. I’ve never stepped forward to serve in this capacity.

Why not?

I’m frustrated that I haven’t made myself more accessible. I want to say this humbly, but I am a widely respected engineer and urban planner. If I were working on a complex project in an established neighborhood, I’d want someone like me advising. I teach this stuff. I travel the country helping communities do it better. But throughout this entire thing, nobody at my parish has ever asked for my advice. I don’t think that’s their fault.

It’s the same with the city. I’ve volunteered my time. I’ve offered to meet with staff—regularly or ad hoc—to assist, to provide training. Free of charge. Nothing. I served on the planning commission. I’d do it again if I thought it mattered. It wouldn’t, but I can’t absolve myself from the reasons why.

We have a neighborhood association. I’ve attended meetings. I’ve participated. But we have a couple of “always say no” voices who shut down most new ideas. I find it exhausting. I don’t want to fight. I just want to be helpful. So I drifted.

The truth is, when I do an accounting of my own participation, I have to acknowledge that I’ve largely checked out.

Strong Towns is growing. The work we’re doing is reaching more people than ever. I’m pulled in a thousand directions, often worn thin, but the impact is undeniably real. The ideas have taken root. The movement has momentum, a revolution quietly gaining speed. This is where I spend my energy.

And so, when the day ends, I don’t find myself volunteering. I recharge by tending my garden, reading a book, walking the dog, and being with my family. I had even planned to skip the meeting where the church project was voted on. I only went because people started texting me. I turned on the YouTube feed and heard the project architect testify to something categorically untrue. Only then did I put my shoes on.

So I have to ask myself: Do I really love this place as much as I say I do?

How could I claim to love my wife if I didn’t spend time with her? How could I say I love my children if I didn’t speak with them daily?

In the Catholic tradition, we say “faith and works.” So where are my works?

If I’m honest—really honest—at a time like this, I’m not doing the work here. And the things I love suffer because of it. I’m having a hard time living with that tradeoff.

In front of my church, there’s a statue of St. Francis. When I was a child, it stood on a pedestal. Elevated just above eye level, it created a trick of perspective; St. Francis looked taller than he was. Larger than life. Majestic. It was part of the awe I felt for the whole place.

Years ago, during a previous project—one that, sadly, also involved buying homes, tearing them down, and expanding parking—the statue was moved to the rear of the church. It ended up near a dumpster, in a spot almost no one would see. I remember walking past and feeling quietly heartbroken.

Today, St. Francis is back out front. I didn’t know this was happening, but the plan had always been to place a large sign there—one scaled for drivers going 30 miles an hour—and to put the statue next to it. The effect is hard to miss. No longer elevated, the diminutive St. Francis now crouches beside our message. To reach the target audience (drivers), the letters on the sign are larger than the head of our patron saint. He peeks out meekly from the side, pointing almost as if to suggest the parking is in the back.

I don’t think anyone notices. I don’t think anyone cares.

This, as Chris Arnade put it in his keynote address at our National Gathering, is now the kind of place people “fast-forward through” on their way to other things.

But I notice. And if I’m honest with myself, I’ve found it convenient to see walking past that statue as a kind of penance. A small, daily reminder of my failings. The ego in me says it’s my cross to bear. But the truth is, nobody did this to me. It happened. I watched it happen. I didn’t show up. I didn’t prioritize it.

This wasn’t done to me, it was done with me, with my acquiescence.

My parish has gone to some effort to light up the sign, more than a thousand lumens aimed at making sure anyone driving by at night knows this is a Catholic church. As if the cathedral behind it, with its massive stained glass windows, didn’t say that clearly enough.

One recent night, I was out walking. Someone had left a light on inside the church. It partially illuminated the giant stained glass window above the front entrance. It was so beautiful that I stopped and took a picture.

Today, I’m hurt. I’m frustrated. But I know the beauty is still there.

If we aim the light just right, the beauty shines through.

I need to be better at shining that light.