I grew up in Baxter, Minnesota, on a farm homesteaded by my great-great-grandparents. I still live in the adjacent city of Brainerd. That makes it especially strange to watch what’s happening at the intersection of Highways 371 and 210, a place I’ve known through its many iterations over the decades.

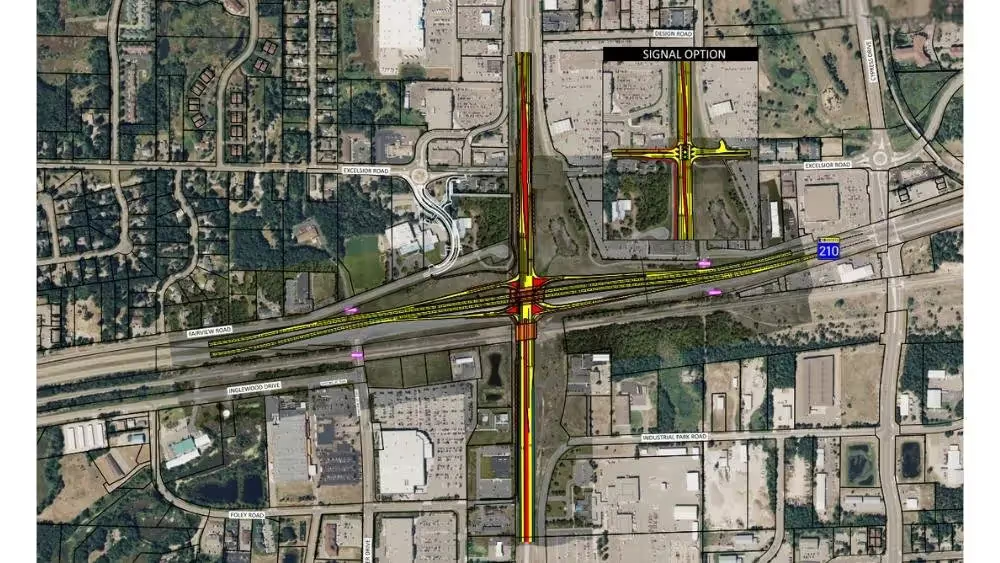

MnDOT is preparing to spend $58 million on a project they’ve dubbed the “buttonhook.” It’s a sprawling interchange that will elevate Highway 371 over both the railroad and 210. The centerpiece of the design? Six roundabouts, five of them newly constructed, wrapped around a pair of 30-foot retaining walls. The whole thing is engineered to keep traffic flowing to and from strip malls, fast food franchises, and big box stores, places like Costco, Fleet Farm, and (until it closes in September) Cub Foods.

Even the visual renderings of this project are absurd. To the untrained eye, it looks like a highway engineer’s fever dream. To anyone familiar with how our transportation system works, it looks familiar in all the worst ways.

As I wrote last year when the project's seemingly immaculate conception was announced, this is not an infrastructure project designed to solve a pressing local problem. It’s the inevitable result of a funding-first approach to transportation investment. MnDOT had access to funding through our infamous Corridors of Commerce program. Local officials were encouraged to “get in the queue.” And once the money was on the table, a coalition of state, county, and city agencies moved to justify the project’s existence.

No one asked the hard questions: Is this the highest priority we have? Is this the best use of public funds? What problem are we solving, and for whom? Even typing these questions feels absurd because, while they’re the right ones to ask, they will baffle the people closest to the project because there isn’t even a mechanism for asking them.

Instead, we got the usual justification, the get-out-of-jail-free card: It’s free money to fight congestion. You’re up in the queue. Do you want the money or not?

Yes, the intersection gets busy, especially on summer weekends, when lake traffic spikes. But are we really building a six-roundabout interchange for Friday afternoons in July?

Let’s be honest: This isn’t about traffic congestion. If it were, we’d be solving for traffic flow, not access. Solving for congestion would mean closing intersections, removing access points, and eliminating traffic signals, the very things that cause the backups and crashes in this corridor. The traffic signals at Excelsior and Golf Course Drive are the primary sources of delay and conflict. Eliminating them would do more to improve congestion and safety than any roundabout ever could.

But reducing congestion isn't the priority here. The goal is to preserve — at ridiculous expense — access to strip retail along a high-speed highway corridor. MnDOT wants to move cars quickly through Baxter. Baxter’s (largely national franchise) retailers want the drivers of those cars to stop and shop. The resulting compromise satisfies no one, costs a fortune, and looks plainly ridiculous to anyone not steeped in the cult of traffic modeling.

This is a project designed by engineers with too much funding, too few ideas, and no clear guidance on prioritization. It's what you get when you try to reconcile two fundamentally incompatible goals: highway speeds and access to strip development. The buttonhook doesn’t fix that conflict; it institutionalizes it, pouring asphalt over a bad idea so we don’t have to confront the reality, at least not yet.

Worse, we can clearly see how it’s being built for a future that’s already disappearing.

Just weeks ago, Cub Foods announced it’s closing its Baxter location, a big box store located directly adjacent to the project footprint. We’re going out of our way, spending tens of millions extra on this project alone — not to mention making the corridor more dangerous — to provide access to a set of really fragile businesses, one of which is already closing. That’s not just tragic. It’s delusional.

And yet, this is the natural evolution of the development model Baxter — and large swaths of America — embraced more than two decades ago. When Highway 371 was routed around Brainerd in the late 1990s, Baxter became the poster child for a certain kind of suburban success: big boxes, chain restaurants, asphalt, and parking as far as the eye could see. The tax revenue rolled in. The city looked prosperous.

In a purely financial sense, this was merely a sugar high.

We’ve called it the suburban Ponzi scheme: high upfront costs paid by others, short-term budget wins for the city, and long-term obligations that quietly pile up. The buildings are fragile, designed for single tenants. They’re easy to abandon and hard to reuse. The streets and pipes and signals require maintenance that the city can’t afford. And when the retail cycle shifts — which it always does — the city is left holding the bill without the tax base they imagined they’d have (which was never enough, anyway).

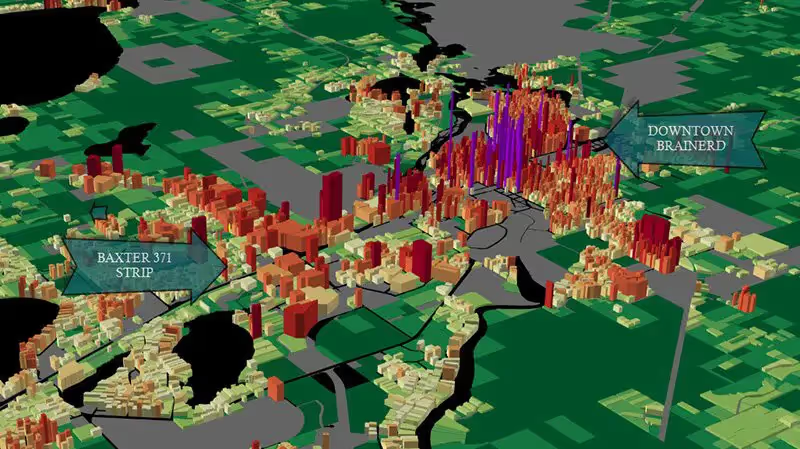

Even in a state of decline (with some signs of improvement), downtown Brainerd is more financially productive than the Baxter strip. The value per acre is higher. The public’s return on investment is better. The buildings are adaptable. The streets are naturally walkable, bikeable, and connected to thousands of people living just blocks away.

But we’re not investing in that. We’re building roundabouts and retaining walls to preserve the illusion of transaction-based wealth that is Baxter’s suburban strip.

The buttonhook is not a one-off failure. It’s the physical manifestation of a larger problem: our refusal to let go of the stroad. The stroad promises everything — speed, access, growth, prosperity — but delivers none of it. And every time it fails, we double down.

So, Chuck, what should we do instead? Cars are backing up for miles. People are being killed in this intersection and along this entire strip. People are trying to bike and walk, and, while the buttonhook isn’t perfect, it makes things better. What is your plan?

If we want to make an investment in traffic flow — which is what MnDOT should be doing — and we want to do it with an eye to safety and cost effectiveness, then the answer is clear.

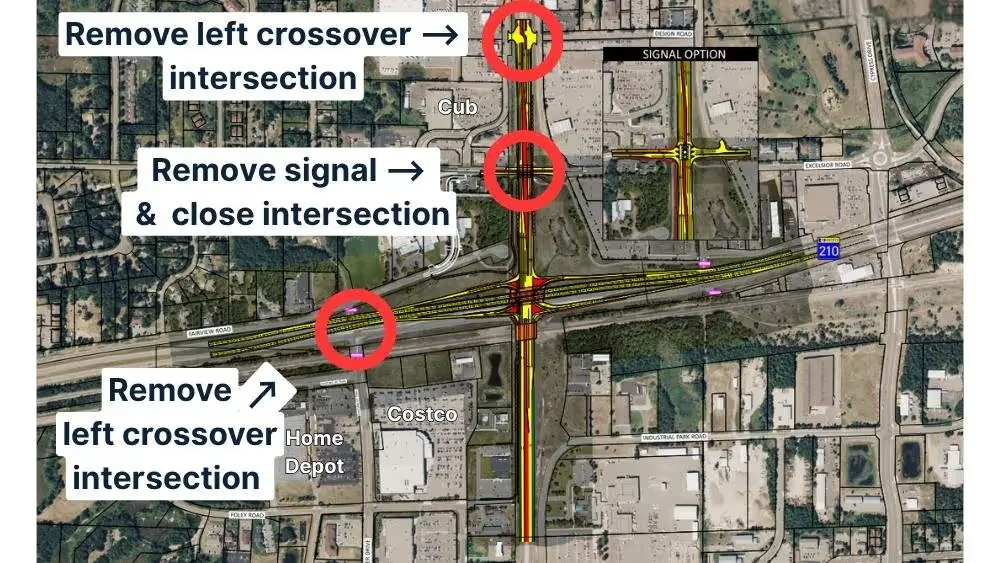

MnDOT should build the single-point urban interchange design they offered as an alternative. However, instead of building an interchange at Excelsior and Golf Course Drive, they should remove the signal there and close the intersection. This would cost a fraction of what is being proposed and would better address the regional traffic issues at the 210/371 intersection.

Some of that savings (a pittance, really, compared to the $58 million proposed to be spent) can be used to remove the left crossover intersections throughout the 371 corridor as well as along Highway 210, particularly the access to Home Depot and Costco. The backups and violent collisions these intersections create are little justification for slightly better access to everyday low, low prices.

If the city wants an interchange at Excelsior and Golf Course Drive, if the city wants roundabouts and premium access to the national chains that have barnacled to the state’s transportation investment, city taxpayers should pay for it. If it’s a good investment, then the city of Baxter can step up and make it happen. If it is merely another corporate subsidy bought with suburban socialism for commuters and some free money for the city, then why are we doing it anyway?

I’m sorry to the people wanting to bike and walk across this high-speed corridor, an environment where they are less than an afterthought. If the state wants to do something for them, we should recognize that their plight is not a transportation problem but a land use problem. Assisting in building more housing and shopping opportunities in nearby Brainerd — which is much more walkable, despite what MnDOT has done and is planning to do to it — would not only cost less, it would provide a much safer experience along with a higher quality of life.

Or we can build the buttonhook. Then act surprised when taxes rise, services decline, housing becomes even less affordable, there are few good jobs, and it feels like the insiders always win while the little guy never gets a break.

This project isn’t a one-time failure. It’s the system working exactly as designed: subsidize the fragile, reward inertia, and call it progress. All for a problem that hardly exists, even though we're, admittedly, hyper-sensitive to it.

Instead, imagine if we redirected even a fraction of this effort — this money, this engineering talent, this public attention — toward the real challenges our communities face.

Systems can be changed. We don’t have to keep doubling down on delusion. We can build strong towns instead.

Click here to read Chuck’s follow-up columns, where he explores the congestion, safety, and economic issues of this project in detail.

.webp)