The Neighbor's Dilemma

Residents stand up at the end of the public hearing. Source: Sarasota County Commission

I walked into the lobby of the county administration building in Sarasota, Florida one afternoon this August to a throng of mostly white-haired folks cheering and high-fiving. In fact, I'm not sure you could have found more white-haired folks cheering anywhere else this side of a Barry Manilow concert.

The white-haired folks (and some younger ones) in question had just emerged from a packed County Commission hearing at which the commission denied a developer's petition to build 35 new homes in an existing residential subdivision of 403 homes. The 35 homes were slated for an open expanse of grass and weeds at the back of the subdivision that had once housed a water-treatment facility, before the neighborhood was connected to county water and sewer lines in the 1990s.

The petition was denied for a complex array of legal reasons which don't much matter to my argument here. The neighbors opposed the 35 homes for their own set of reasons, which were made clear in public comment after public comment: traffic on neighborhood streets. Disruption of their peace and quiet during construction. Loss of green space.

(Two members of a large group of neighbors, with matching yellow name tags, speak in opposition to 35 new homes in a Sarasota subdivision. Source: Sarasota County Commission)

There's a prevailing narrative out there about cranky white-haired suburban NIMBYs. It says they're selfish and can't see the bigger picture. That they have antiquated views and don't get that the public wants mixed-use, walkable neighborhoods now. That they have too much time on their hands and nothing better to do than go to public meetings and rabble-rouse.

I think these characterizations all miss the point, as does the "NIMBY" pejorative itself in most cases. Homeowners who oppose the kinds of things that many urbanists find sensible, and that make for more fiscally-sustainable and productive places, aren't oblivious, exceptionally selfish, or deserving of being mocked or demonized. They are responding to a set of very rational incentives, and those rational incentives are at the heart of why it's going to be extremely difficult to alter the course of the Suburban Experiment in a meaningful way.

The Prisoner's Dilemma is a famous illustration from game theory of why individuals pursuing their own rational interests may fail to arrive at a mutually-beneficial outcome. I'd argue that urban / metropolitan residents face their own sort of prisoner's dilemma when it comes to land-use planning. (Credit is due to Daniel Kay Hertz of City Observatory for inspiring me with a somewhat different application of this idea to land-use policy.) Call it the Neighbor's Dilemma. If you and I live a few miles apart in the same city, development decisions that are good for me aren't necessarily good for you. What's good for you might not be good for me. And what's good for us as a collective is often elusive and doesn't end up having a constituency willing to go to bat for it. This collective-action problem is far more problematic in car-dependent communities than in traditional, walkable ones, for reasons I'll elaborate on below.

Let's zoom out for a minute. This is the part of suburban Sarasota County surrounding the subdivision where that rezone was under consideration:

(Source: Sarasota County Planning and Development Services rezone petition staff report)

Outlined in yellow is the "open space" whose neighbors successfully saved from becoming 35 new homes. An empty field of grass, tucked away at the back of a subdivision. Sure, it could one day be turned into a park for the use of neighborhood residents, I guess. But suburbia is full of little pockets of land like this, most of which will never be put to meaningful use. What is the cost of decisions like this, repeated over and over across the landscape? Essentially, a "swiss cheese" development pattern full of holes.

In the above map, observe the sheer amount of land in this part of town that, at a glance, constitutes "non-places." The prevailing pattern is relatively densely-packed residential subdivisions surrounded by a whole lot of wooded land. Most of this land is not open to the public. It's not part of a park. It's not part of someone's yard. It's not a street or road or sidewalk or any sort of public facility. It's just there. It's there because developers commit to a certain set-aside of "open space" (as distinct from usable recreational space) when they build subdivisions, and any later attempt to go back and build on that open space is liable to be met with predictable, fierce resistance from the existing residents.

(Source: Wikipedia)

The consequences writ large of all of this inefficient land use are predictable: More wilderness paved over for new housing. Longer driving distances between destinations. Traffic congestion from the increased amount of driving that area households must do. More miles of roads and sewer pipes that must be maintained to support the same population. An unproductive land-use pattern that does not generate the wealth to pay for its public infrastructure. The looming threat of insolvency when it comes time to repair or replace said infrastructure.

Southwest Florida is a rapidly-growing region. The population of Sarasota County alone is projected to increase by 100,000 people by 2040. Where is it going to house those people? Pave over more of paradise, doubling down on the suburban pattern? Or do infill development— i.e. find ways to squeeze more value out of infrastructure investments already made in existing neighborhoods, the fiscally and environmentally prudent approach. And it will help to move wherever we can toward mixed-use neighborhoods.

So are the folks who turn out to oppose those incremental changes the villains in this story? Let's zoom back in to that Commission chamber. I went in with an open mind trying to listen and empathize. What kinds of things were they saying?

The most common concern was traffic: every single trip in or out of these 35 homes, at the very back of a large subdivision with only one exit, would be in a car, down 23-foot wide streets with no sidewalks that are used by residents for strolling and walking their dogs. At busy times of day, I can imagine that being noticeably more cars.

(A street in the neighborhood in question. Source: Google)

A related, and also repeated, complaint was that heavy construction vehicles would be traversing those 23-foot wide streets for a year or more, causing major disruption to neighborhood quality of life during that period. Can I argue with that? Not really; it would no doubt be disruptive.

Should the subdivision have been built with only one exit onto an arterial road, instead of a more connected street grid? No, but it was. Do people have a god-given right to demand that no one drive in front of their houses? No. But do they have an incentive to use their voice in the democratic process to minimize those impacts? Sure, they do.

Some of the complaints at the podium were overstated—one speaker objected that the headlights of cars turning onto the new street after dark would shine "right into her living room"— but who among us hasn't ever overstated a case in the name of making a point or winning an argument?

It's frankly true that these people bought into the neighborhood with the expectation that the property in question wouldn't be developed. Most were expressly told that the subdivision was "fully built-out" and were surprised to learn last year that the developer could add more homes. They were angry because their expectations were now being violated.

I could argue all day about whether these objections are serious or frivolous, or whether they outweigh the developer's property rights or the collective interest in using land efficiently. Those arguments almost never move people who don't want to be moved. The kind of person who chose to buy property in a gated HOA subdivision did so for a reason.

More important than telling them why they're wrong and expecting to change minds (you won't) is understanding the fact that they have zero incentive other than altruism to adopt the other side on this issue. What do the residents of the 403 existing homes in this subdivision possibly have to gain from 35 additional homes? There is only downside for them, no upside.

This fact, though—and here's the important part—is actually a function of the car-dependent development pattern. It's not inherent to all cities.

The Car-Dependent Suburb's Response to Development

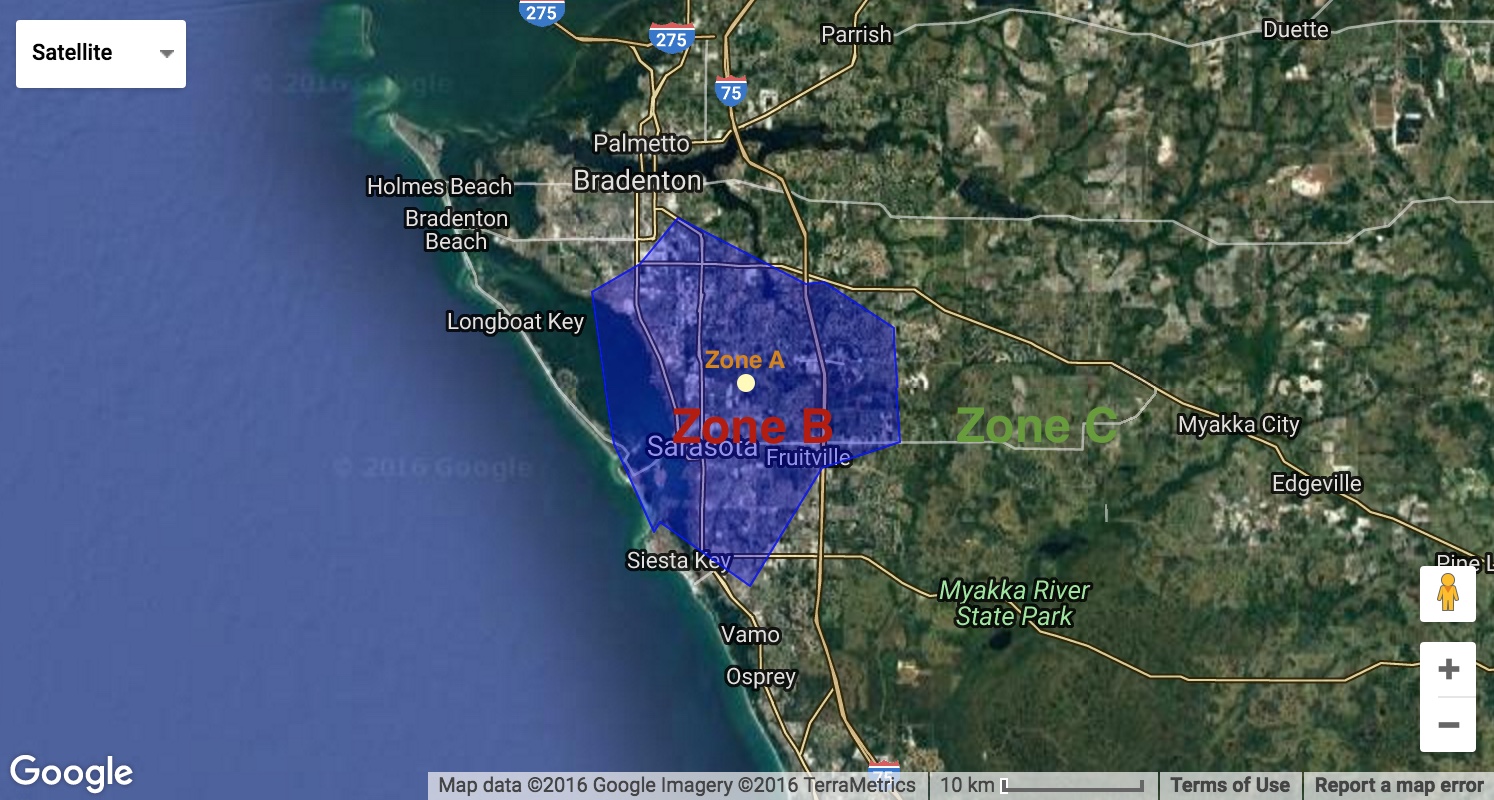

Think of it this way. You can roughly divide your city or metropolitan area up into circles or zones of concern—you have different incentives based on how proximate an area is to you or how remote.

Source: Google. Zone B boundaries creating using FreeMapTools.

Zone A is your immediate neighborhood, let's say, within a 20-minute walk of your home. In a city where the prevailing mode of transportation is the private car, what's important to you to have in Zone A? Probably safety and comfort. Pleasant aesthetics. School quality, if you have kids. Low crime. These factors impact your life every day, and you will show up to a public meeting and pick a fight over them if you have to.

Zone B, out of walking distance but within 20 or 30 minutes' travel time by other means (i.e. your car), is the broader city in which you likely work and where you spend your time and your money. You want amenities: retail and entertainment options. You want efficient mobility so you can access those amenities. You have an interest in development in Zone B, including residential development, because those residents will be new customers for businesses that you can then patronize. If enough people move in, maybe your town will finally get that Trader Joe's you've been hoping for! But your utility is maximized if all those new people move into your Zone B, and none of them into your Zone A.

Zone C is the rest of the metro area beyond convenient travel range, and the surrounding undeveloped land. Your primary interaction with Zone C may well be when you leave town to travel somewhere or get out and enjoy nature. You'd like nature to be accessible. You don't want traffic to be abysmal on the highway out of town. You certainly don't have an interest in endless sprawl, and if Trader Joe's opens up an hour from you, that's not so exciting—you probably won't be making such a trek too often.

Not sure why these folks are at this meeting, but they're definitely angry about something or they wouldn't be. Source: Wikipedia

I'd sum it up this way, in a car-dependent community: Residents have incentives to be strongly anti-development in their Zone A, moderately pro-development in their Zone B, and moderately anti-development in their Zone C.

But your Zone B is someone else's Zone A, and vice versa. And people generally won't pack a public meeting over a particular issue unless they have a strong personal stake in the outcome. So the public hearing for any development approval is packed with the immediate neighbors, and—surprise surprise—they're always unanimously opposed. The perception that elected officials in suburban places get that their residents hate new development and want absolutely nothing built absolutely anywhere must be overwhelming.

The result is either an elected body that finds itself consistently voting against the opinions of its most vocal constituents, or one that takes the easy road and approves largely greenfield development, which doesn't have a "Zone A" constituency to oppose it yet. (Frogs and birds and deer haven't figured out yet how to fill out comment cards or use a microphone.) Are we surprised when they take the easy road?

The Walkable City's Response to Development

In walkable cities, the incentive structure works differently. Your Zone A now overlaps quite a bit with your Zone B: your neighborhood is plausibly the place where you work, shop, and play. New development down the street might still decrease your quality of life in some respects. But it might also increase it. It might get you that cool coffee shop or that Trader Joe's. It might get you higher-frequency transit. It might get you increased public safety by way of eyes on the street.

The biggest detrimental effect of residential density in a car-dominated setting, and invariably the biggest thing angry neighbors come out to speak against, is traffic congestion. But pedestrian congestion, outside of tourist destinations or major events like street fairs? Not really a thing.

It's not that there's no opposition to development in walkable cities. There is. But the battles are fought over things like views, historic preservation, design, public space. Sometimes over a desire for socioeconomic exclusivity—low-income housing remains unpopular most everywhere. These battles can get ugly. But I'd suggest that in general there's a lot more room in walkable places to reach a win-win outcome between residents and developers.

The problem with a car-dependent place is that any development at all may be a net negative for the established residents of a neighborhood. There is effectively no concession the developer can offer that turns it into a net positive in the short run. In the long run, infill development is needed to improve the fiscal solvency of these places and to create opportunities to transition away from car-dependence. But in the short run? I get more traffic in front of my house, and with me on the roads I have to drive to the businesses I patronize or work at.

Suburban places that succeed in making the transition to strong towns over the coming years will be the ones that figure out ways of breaking through this logjam of citizen opposition to even incremental change. I'll save the discussion of how to do so for another post (or the comments on this one), but suffice it to say, I think we need to be talking about interests and incentives, not appealing to a sense of altruism or shared civic destiny to get the job done.

Sunbelt cities have long prided themselves on having affordable and abundant housing. However, they’re now seeing housing construction stagnate and rapidly rising costs. Abby is joined by trained architect and video creator Rachel Leonardo to discuss whether these cities can course correct.