A Brief History of the Fair Housing Act and its Applications Today

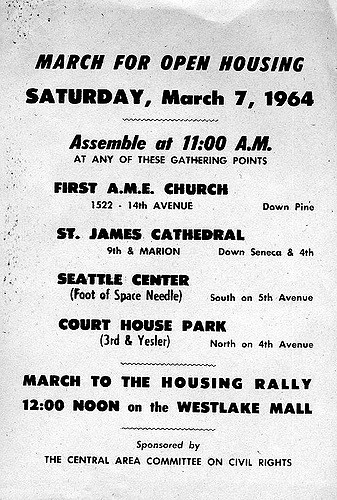

Image from the Seattle Municipal Archives

Most of you probably didn’t notice the Supreme Court decision handed down in June 2015 regarding fair housing law. Some of you may not even know what fair housing is. But it matters for our discussion this week about building walkable neighborhoods with mixed-use, multifamily buildings instead of filling our nation with ever more suburban developments, funded by the federal government. The Fair Housing Act is a federal law that “makes it unlawful to refuse to sell, rent to, or negotiate with someone because of their race, gender, religion, etc.” The Fair Housing Act passed a week after Martin Luther King’s assassination. It was a landmark civil rights act that attempted to push back on decades of housing discrimination, and it still has bearing today.

The Regional Plan Association's report, "The Unintended Consequences of Housing Finances," mentions fair housing and the precedent it sets for expanding housing options supported by federal mortgage loans. It specifically brings attention to a recent Supreme Court ruling on Fair Housing, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. Inclusive Communities Project. The RPA report explains that HUD rules issued after this case “highlight the need to both break the cycle of disinvestment in racially-concentrated areas of poverty and to expand the amount of affordable housing in areas with good schools and other opportunities. Reforming financing rules to make it easier to finance mixed-use development will remove an impediment to investment that can help achieve both of these goals.” I’m going to break down the history of fair housing, its implications today and what it means for current federal mortgage policies.

What is fair housing?

Here is the basic explanation, from the HUD website:

Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (Fair Housing Act) prohibits discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of dwellings based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. Title VIII was amended in 1988 (effective March 12, 1989) by the Fair Housing Amendments Act, which:

expanded the coverage of the Fair Housing Act to prohibit discrimination based on disability or on familial status (presence of child under age of 18, and pregnant women); and

established new administrative enforcement mechanisms with HUD attorneys bringing actions before administrative law judges on behalf of victims of housing discrimination.

As I wrote a couple weeks ago in my essay about Flint, this is why we have government: to regulate issues that affect the wellbeing of Americans, which we don’t trust private companies – in this case landlords, realtors and developers -- to self-regulate.

Fair Housing is, of course, still a problem. Just because a law exists doesn’t mean that it is consistently enforced. In an ideal world, the Fair Housing Act would mean that people of color, women, people with disabilities, and people of different religions, would all be given a fair chance to buy or rent housing the same as any white male. In reality, Fair Housing claims are still filed regularly and racist slumlords still prevent people from accessing the housing they want. The Supreme Court case last June also made clear that there are other ways in which housing practices can be discriminatory, some of which, the federal government has, itself, been responsible for.

Public housing in New York City. Photo by Ken Lund.

What does the recent Supreme Court case mean for fair housing?

As the RPA report explains: “The June 25, 2015 decision by the Supreme Court in Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs (TDHCA) v. Inclusive Communities Project upheld the government’s obligation to affirmatively further fair housing when policies result in disparate impacts.” This case was essentially about segregation. The TDHCA had been supporting the creation of affordable housing via the popular Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) program, which gives developers a tax break if they rent a certain percentage of their units at “affordable” rates.

The problem, the Inclusive Communities Project argued, was that the affordable housing funded through LIHTC was only being built in poor minority neighborhoods. This meant that poor minorities only had access to housing in their existing, segregated neighborhoods. They were effectively excluded from wealthy white neighborhoods where they might have had the chance to attend better schools, enjoy more accessible amenities and live on safer streets, if only affordable housing existed in those neighborhoods.

In the majority opinion for the court case, Justice Kennedy wrote, “In striving to achieve our ‘historic commitment to creating an integrated society,’ we must remain wary of policies that reduce homeowners to nothing more than their race. But since the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968 and against the backdrop of disparate-impact liability in nearly every jurisdiction, many cities have become more diverse.”

Essentially, the Supreme Court case clarifies that fair housing laws extend beyond simply refusal of an individual landlord to rent to a minority. Fair Housing also means that housing policies and funding cannot negatively impact one demographic over another.

What does Fair Housing have to do with loan reform?

“Federal mortgage priorities play a role in disproportionately disenfranchising low income communities.”

In the case of mixed-used, multifamily buildings, HUD has, with its mortgage funding, chosen to primarily support the creation of single-family dwellings, which are far more accessible to white middle class people and far less accessible to minorities in poverty. In the last quarter of 2015, black homeownership rates were 70% lower than white home ownership rates (US Dept. of Commerce). HUD's mortgage policies have prioritized single-family housing options -- often the purview of wealthier white families -- for decades, while discouraging the creation of other more affordable mixed-use and multifamily buildings. As demand for walkable neighborhoods has increased, the cost of living in those neighborhoods has also gone up, with supply lagging behind due, in part, to the federal government's mortgage policies which mainly prioritize single family living over walkable, mixed-used, multifamily living. Low income people, so many of whom belong to a class protected by Fair Housing law, could greatly benefit from living in those walkable neighborhoods, but cannot currently afford to. Thus, federal mortgage priorities play a role in disproportionately disenfranchising low income communities, and run counter to the Supreme Court's recent fair housing ruling.

The angle of the whole RPA report is that HUD’s own policies are contradictory and outdated. HUD has made it clear that it knows the value of walkable neighborhoods and wants to encourage their proliferation. HUD cares about the issues of concentrated poverty and affordable housing, and the Supreme Court's 2015 Fair Housing decision makes it clear that the federal government is in favor of desegregation and increased access for minorities and other underserved communities through housing. The RPA report recommends that HUD adjust its loan policies in order to align with these stated priorities and values, and allow greater access to more diverse affordable housing options.

This gets personal for me because I worked at HUD, still have many friends there and have worked for other anti-homelessness agencies that are served by HUD funding. I believe HUD is an important department of the federal government, doing a lot of good in this country. But it needs to shift its loan priorities to allow for the creation of more mixed-use multifamily buildings in walkable neighborhoods. This shift will help enable HUD to achieve its goals of desegregation and increasing access to affordable housing.

(Top photo by London Scout)

Rachel Quednau serves as Director of Movement Building at Strong Towns. Trained in dialogue facilitation and mediation, she is devoted to building understanding across lines of difference. Rachel has served in several different positions with Strong Towns over the years, as well as worked for local and federal housing organizations. A native Minnesotan and honorary Wisconsinite, Rachel attend Whitman College for her undergraduate and received a Masters in Religion, Ethics, and Politics from Harvard Divinity School. She currently lives in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, with her husband and two young children. One of her favorite ways to get to know a new city is by going for a walk in it.