We Are All Detroit

There’s something Strong Towns staff members have noticed as we’ve accompanied Chuck Marohn on his Strong America Tour. Again and again, one of the most powerful moments in the Strong America presentation is when Chuck declares that “We are all Detroit.” For many who haven’t spent much time that city, the collapse of Detroit can be dismissed as an anomaly, the extreme case that somehow makes us feel perversely better about our own community’s health. But Chuck says that is the exact wrong reaction; Detroit is a glimpse of what’s at the end of the road for nearly every American city and town, unless they can change their present course. We are republishing this classic piece (gently updated for today) in the hopes that it will continue to inform local and national conversations about what makes our cities weaker, and what makes them stronger.

— The Editors

Michigan Central Train Station in Detroit. (Photograph from Wikimedia)

We Are All Detroit

Detroit is not unlike any other city. In fact, Detroit embodies so much of America. Whether it is race, corporations, government or unions, I think it is impossible to visit Detroit even today and come away believing the place is an anomaly of North America.

When a person is infected with HIV, their immune system breaks down. Ultimately they become so weakened and frail that they are susceptible to common ailments that a healthy body could fight off. The final cause of death for someone with AIDS is often pneumonia or infection, but it's clearly understood that this is simply the final ailment. What killed them was acquired immune deficiency syndrome, an attack on their body's resiliency.

What the final ailment for Detroit was simply doesn't matter to me. The auto-centric style of development undermined the resiliency of the city, tearing down social, political and financial strength that had made Detroit one of the world's greatest cities. Once this strength was undermined, once Detroit became a fragile city, it was only a matter of time.

Detroit is the story of America: hard won, incremental gains replaced with an illusion of wealth ultimately sustained by a mountain of debt. We can pretend that's not true, but it is. My hope for the future of America comes not from anything going on in Washington DC, Wall Street or Silicon Valley, but in the ingenuity and spirit of the people who are flocking to the core of Detroit today, rebuilding it in that traditional way, one block at a time. We all need to learn from them.

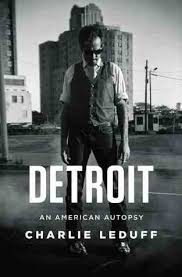

Detroit: An America Autopsy

“Go ahead and laugh at Detroit because you are laughing at yourself.”

I recently read a powerful book by Charlie LeDuff called Detroit: An American Autopsy.

For me, Detroit is both a fascinating and scary place. Fascinating because it is a glimpse into America's future and scary because the future is grim. I've long held that Detroit is not some one-off place that we can discount but that it actually represents the logical outcome of the Suburban Experiment. Here's something I wrote about a simplistic explanation of Detroit back in 2012:

It is more complex than simply (1) we were successful and grew, (2) people left and now (3) we don't have enough money to maintain everything. There is something between the growing and leaving that is critical... I've long seen Detroit as the canary in the coal mine and not some type of anomaly we can all sneer at.

And even way back in 2009, I wrote:

And if you think it can't happen, that we can't over-subsidize, overbuild and over-extend ourselves into collapse, just take a look at Detroit. While there are many complexities to the situation there that make simple analysis somewhat questionable, at that basic level, the rest of the country is trending towards Detroit, not away.

It was stunning to me, therefore, when LeDuff opened his book with the same basic argument: We can pretend that Detroit is a case of corruption or incompetence or racial issues or globalization—and there are certainly many nuances and complexities—but at the end of the day, what has happened and is happening in Detroit has a lot of commonality with nearly every other city in this country.

LeDuff summarizes this succinctly in an interview he did on the Colbert Report:

You better look at Detroit because that's what happens when you run out of money. And we're all scared to death what they're doing in Washington...you're printin', we're spendin', we're not spendin', sequestration.... Get the money together or the kids don't have a future.

An auto-oriented stroad environment

Our Local Governments Are Going Broke

There's an entire group of our readership at Strong Towns that simply checks out when we start talking about finance or Federal Reserve policy. I get the emails from you guys. Hey Chuck, get back to bashing engineers and planners....that's what people want....they want to hear you say that sprawl is bad...they don't want all your goofy thoughts on the economy... To those readers, I'm sorry, but we have to get the money together. If you don't understand that, you don't understand Strong Towns.

Our local governments are going broke. And I'm not just talking about the Harrisburgs, San Bernardinos and Detroits. I'm talking about basically all of them, the only possible exceptions being a handful of anomalies I'm simply not confident lumping in with the rest (NYC, DC and SF being the primary ones). The rest are clearly "all in" on the Suburban Experiment to one extent or another, fully committed to maintaining miles and miles of unproductive stroads, sewer systems and water lines for an asteroid belt of strip malls, big box stores and sheetrock palaces surrounding a downtown dependent on direct subsidies and a sea of asphalt parking for a subsistence existence.

The process here is pretty clear. In the name of growth and efficiency, cities embrace the auto-oriented pattern of development. This weakens the bonds of the traditional neighborhoods, changing the value paradigm from being one of neighborhood vitality to one of automobile mobility. Now the most valuable places are the ones with the most stuff, the biggest parking lot and the quickest in/out time. Let this approach simmer for a generation and the community, with the support of zoning codes, will segregate into pods based on income and level of affluence.

Photo by Andy Walker

The Recipe for Urban Decline

Now you have the recipe for full decline. As the second life cycle of the Suburban Experiment kicks in, more growth and a little debt is used to make ends meet. Declining neighborhoods are gradually written off as being places where "those people" live, and "they" just don't have the same ethics and values as the rest of us. (By the way, identifying "those people" transcends race as I see the same labeling of the disadvantaged here in my 99.5% Caucasian community.) This all makes it easier to divert precious resources to growing (read: affluent) neighborhoods and neglect the others.

As those declining neighborhoods continue to grow as a percentage of the community, we try heroic interventions. Perhaps we build a stadium or label something an entertainment district. Maybe we simply tear down buildings and pay someone a subsidy to come in and rebuild something less offensive. Either way, the decline continues because the vitality and natural mechanisms for maturing have been sucked out of the neighborhoods and what has replaced them on the periphery is not financially viable. The clock is ticking.

Eventually the affluent coalesce in a handful of neighborhoods. Where they are outside of the city limits, the collapse of the place may accelerate, but even when these wealthy neighborhoods are within, one type of corruption (mob or gang style) is simply replaced with another (crony). Police and fire cutbacks. Reductions in park budgets. Public buildings in decline. Streets that are in such disrepair they are essentially abandoned.

Look around. Don't you see it?

Eventually, we reach the condition of Detroit. As LeDuff describes it, it feels a lot like some of the third world. Call the police, they don't show up. If they do, it takes thirty minutes or more. Same with the fire department. People who can afford it hire their own security. The rest carry weapons and travel in groups. Money is allocated for fixing things like the cracked floor at the fire hall, but nobody knows where it went. The floor is never fixed. City hall is distant and clearly corrupt, but who among decent people would step up and try to fix it? Decent people need to survive, or they are already having their needs met and, in that case, there is little to be gained for the enormous trouble.

For most of the city and most of the people, things just stop working. A lot of resourceful people find work-arounds. A lot of others don't. LeDuff's book is full of both. It will break your heart.

The Future of Failure

At the same time I was reading LeDuff’s book, I visited Mansfield, Texas, a growing and prosperous distant suburb of Dallas and Fort Worth. Mansfield and the book were an odd juxtaposition. The people I spoke with felt that Mansfield was a great place, that it was doing most things right. Just look at the new mall or the movie theater or the collection of chain restaurants. The idea that the place could ever fail—that it would ever reach the depths of decline of Detroit, let alone follow the trajectory of the suburb up the highway (you know...the one that had been the new place a few decades ago)—was unimaginable to the people there.

“Small scale failure is a chance to learn.”

But it will fail. It is simply not financially viable. Get the money together or the kids don't have a future.

It is important to understand that cities used to fail all the time. Not large cities—they had pretty much demonstrated a need to exist and could generally figure out a way to continue—but we used to have ghost towns all the time. These were small experiments that simply didn't work out.

As with any natural system—which traditional cities were as the product of thousands of years of trial and error experimentation—failure is a necessity for growth. Small scale failure is a chance to learn. What we've done with the Suburban Experiment and the parallel centralized financial experiment the United States has embarked on is to create a system where the only possible failure is large. Catastrophic. All other failures get bailed out, subsidized away or coaxed back to zombie status. This presents the same moral hazard to local governments (and society in general) as it does to too-big-to-fail banks. Go big or go home. (For more on the value of failure, read our Antifragile series.)

There's so much that needs to be done that sometimes I'm paralyzed by it all. I'm not sure if Detroit: An American Autopsy is inspiring me to work harder or putting me into a terrible depression over what I can clearly see coming. Is it unavoidable? Would we simply be better off getting it over with and then moving on?

Last year Charlie LeDuff golfed the length of Detroit, from 8 Mile Road to Belle Island. I watched the video last year and it felt like a simple stunt so I quit a few seconds in. After reading the book, I now understand what LeDuff was doing. I watched the entire video late one night last week, some tears in my eyes at the scenes as I thought back to the book, wishing the stupid news anchor would quit butting in and simply let Charlie tell the story of the city and its people. The tragic, but beautiful, story of a place that we all need to understand. From the video:

Two thousand, five hundred and twenty five strokes and I golfed every inch of it. I'm thinkin' back to what I saw behind me. A city, its people, holdin' on, waitin' for a savior, a savior who may not be coming. I wonder if the people know that the savior might be found within themselves, their neighbors maybe, their families most definitely? The old saying is true: no man is an island.

“We can retreat back into our nice subdivisions, shop at our discount stores and borrow more money to keep it all going today, but eventually we’ll discover that we’re in this together. ”

None of Us Is an Island

And that's the most important thing. None of us is an island. We can retreat back into our nice subdivisions, shop at our discount stores and borrow more money to keep it all going today, but eventually we'll discover that we're in this together.

Our historic way of building places was not perfect. It left many behind and treated many more unfairly. It was slow-moving, chaotic and inefficient. Those weren't disadvantages, however. They were design features. It was the slow-moving, chaotic and inefficient approach that strengthened cities, made them financially resilient and provided the platform for ongoing improvement of the human condition. It was that daily friction of people inhabiting the same space that made cities ultimately work. If we want our kids to have a future, we need to get that back.

We're all Detroit. The sooner we realize it, the sooner we can commit ourselves to building a nation of strong towns.

(Top photo by Arthur Siegel)

There’s a certain artistic quality to abandoned spaces—but if we look a bit deeper, these ruins also hold lessons about patterns of disinvestment and policy shifts that have adversely affected American communities.