The Key to Slowing Traffic is Street Design, Not Speed Limits

On September 8, Wiley & Sons will release the second book in the Strong Towns series: Confessions of a Recovering Engineer: A Strong Towns Approach to Transportation. Chapter five is about building great streets and how it is essential, if we want places that are prosperous and productive, that we focus on how streets build wealth for a community instead of how efficiently they move vehicles. It is impossible to build a place that people want to be in if they don’t feel safe there.

That should be self-evident but, for many reasons, it is not. This is particularly obvious when there is some type of violent collision. Instead of investigating the factors of the street design that contributed to the crash, those in transportation professions are most often heard resorting to platitudes that put sole responsibility on the driver or the person walking or biking.

“Be hyper-aware of your surroundings.”

“Always obey the speed limit.”

“Speed is a factor in 30 percent of crashes.”

“Safety is a shared responsibility.”

And yet, we know that people are sometimes going to make mistakes. Even conscientious drivers make mistakes. People walking, going about their business, are going to make mistakes. No one is going to be hyper-vigilant every moment that they’re out in the world. And why should we have to?

We can't regulate our way to safety. We must design our streets to be safe.

Two simple photos reveal what it means to design a street to be safe, versus counting on the speed limit alone to do the job. This image was created by planner Wes Craiglow of Conway, Arkansas, and shared on social media by the "Transportation Psychologist," our friend, Bryan Jones. We first shared it back in 2015, but it remains timeless, so here it is again:

As Wes points out, this image "is intended to help viewers consider how different street designs makes you feel as a driver, and ultimately affect how you behave behind the wheel. Generally speaking, as depicted by the lower photo, narrower travel lanes, shorter block lengths, and a tree canopy, all contribute to drivers traveling more slowly. Conversely, wide lanes, long block lengths, and open skies, as seen in the upper photo, communicate to drivers that higher speeds are appropriate.”

Look again at the two photos. Imagine yourself behind the wheel of a car on each street. On which street would you drive faster? On which street would you exercise more caution?

“Forgiving” Design is a Misnomer

The first photo looks like tens of thousands of suburban streets all over America. It’s entirely representative of something the transportation engineering profession calls “forgiving design.” The premise is simple: drivers will make occasional mistakes—veer a bit out of their lane, fail to brake hard enough, etc.—and if the street is wide, with high visibility in all directions, and free of immediate obstacles such as trees and fences, those mistakes won’t be catastrophic.

The problem: this street feels too forgiving to a driver. Too safe and comfortable. So drivers speed up. The engineers didn’t account for this aspect of human psychology.

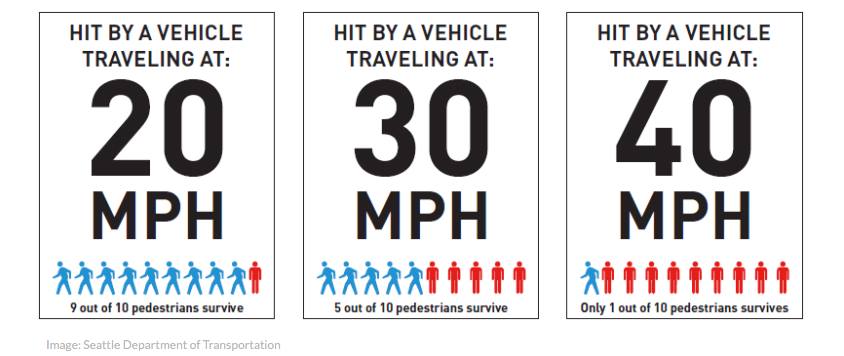

This residential street is built like a four-lane highway, and so even though its legal speed limit is 20 miles per hour, it’s no surprise when somebody guns it up to 40 miles per hour or more down a street like this. It feels natural to do so. It feels safe. But it isn’t safe—because on a city street, unlike a freeway, there might be people around. People who will most likely be badly hurt or killed if a speeding driver hits them.

The Paradox of Street Design: If It Feels a Bit Dangerous, It’s Probably Safer

The second photo, on the other hand, represents the most basic, frugal approach to designing a street for slow speeds. It’s not perfect. It lacks sidewalks or bicycle facilities, which some of our readers might take issue with—and yes, many places ought to have those things.

But this “slow street” does something really profound and important. It causes drivers to slow down, whether or not there’s a posted speed limit or law enforcement present, because of the uncertainty and sense of heightened risk.

The street is narrow. Visibility is limited. Look at that front left corner of the intersection, where a red fire hydrant stands next to a white fence. The lack of visibility there is not a safety hazard: paradoxically, it’s probably the single biggest thing that promotes safety at this intersection. Because if you’re driving here, and can’t see whether a vehicle is approaching from the left, what are you going to do?

That’s right. You’re going to slow down.

Why 20 Miles Per Hour?

If we could keep most urban traffic to 20 miles per hour or less, we could eliminate the vast majority of deaths from car crashes in our cities and towns. We wouldn’t eliminate mistakes—people, both inside and outside vehicles, are going to make them—but those mistakes would rarely be deadly.

The place for wide lanes and “forgiving design” is on a high-speed road. City streets, on the other hand, have to be places for people. We know how to design streets that will slow down traffic automatically, without the need for heavy-handed enforcement, and regardless of what the speed limit sign says. We just need to do it.

If you are interested in learning more about street design and how we can form a Street Design Team to get it right, we have created some pre-order bonuses for people who purchase Confessions of a Recovering Engineer before September 8. This includes “30 Days of Confessions,” a video series we will be sharing soon with those who have pre-ordered the book. You can also immediately check out Aligning Transportation with a Strong Towns Approach at Strong Towns Academy, or the shorter Local-Motive session on “Establishing a Street Design Team.“

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.