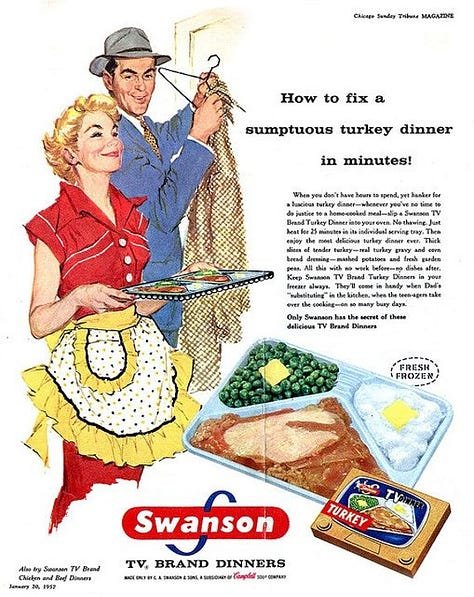

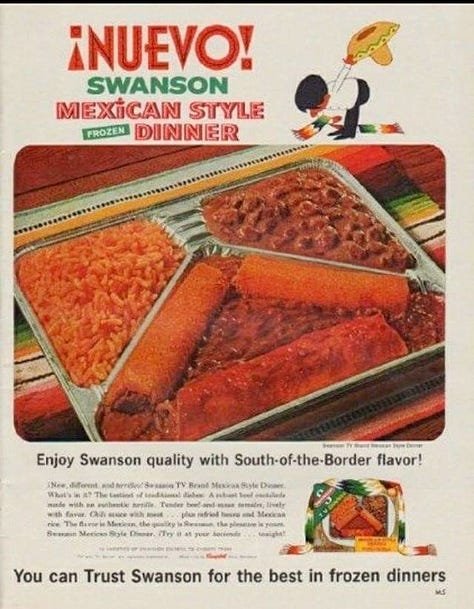

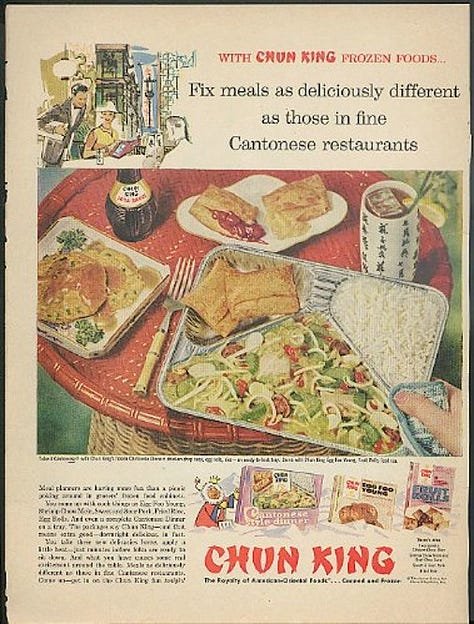

When I was a kid, I thought tv dinners were the coolest thing. You could just grab this box out of the freezer, pop it in the oven or microwave for a little bit, and there’s a whole meal ready for you with no work. There were even several varieties and cuisines available to please every taste, beyond whatever is actually in Salisbury Steak. What’s not to love? Clearly, the future was all about food you could get right out of a machine, and have ready to eat in no time. Efficient! Genius!

Except, something happened on the way to George Jetson’s fantastic future. It turns out, industrially-produced and packaged food was really pretty gross. And bad for us. And oh, by the way, often more expensive than cooking from scratch.

It was slow at first, but eventually people started realizing this wasn’t a good way to go. Julia Child taught us about the joy of cooking good food and enjoying it with others. Alice Waters reconnected us to real ingredients, and food grown nearby. Eventually, enough people reconnected with real food that farmers markets exploded in use, restaurants started focusing solely on local ingredients, and even fast-food chains started marketing more natural products.

Today, we are all foodies. Or, at least, we like to think we are.

The trend that was borne out of industrial agriculture, industrial food processing, and mass distribution has reversed. It continues to reverse, since most people generally love good-tasting, healthy food. We still have our fast-food indulgences. I still have mine (hint: Taco John’s—sorry, Chuck Marohn). But once you learn how to cook for yourself, and do it well, it’s very hard to go back.

The saying now is to “eat like your grandparents did.”

In a similar vein, other societal trends can not only change, but sometimes reverse themselves. Vinyl records have surged in popularity, despite every practical reason not to buy them. They’re not being purchased as much as they were in their heyday, but it’s incredible how much market share they’ve recovered since the depths of the 1990s. If you’d asked me in 1990 if people would still be buying records in big numbers 30 years later, I’d have laughed out loud. Or, ROTFLOL’d.

The list can go on and on. “What’s old is new again,” right?

Primo

If you ever read or watch people who forecast trends, it’s really pretty hilarious. Virtually every forecaster, no matter the field, tends to predict today’s trends will continue into the future, but just 1% more or so every year. I get why people do that. It takes boldness to predict a significant change, either up or down, and it’s much safer to assume tomorrow will be like today, but just a little more so. That’s a better way to keep your job.

It’s also really dumb. Humans and human societies don't work that way. Trends peak and decline. Sometimes they reverse completely. Sometimes they accelerate more quickly. Forecasting the future with "scientific" models has to be among the most ridiculous things we do as humans. We are terrible at it, and likely always will be. It's asking the impossible of us. As Mark Twain said, “Prediction is difficult. Particularly when it involves the future.”

Nothing is inevitable.

I’ve been on record for years that the interest in walkable communities is real, and long lasting. Walkable places are pro-human. They connect to fundamental desires to use our bodies as they’re intended and to see and greet other humans in the flesh, as part of our daily lives. Traditional communities that humans built for centuries were emergent in nature, complex and made by many hands. They speak to something deep within our nature.

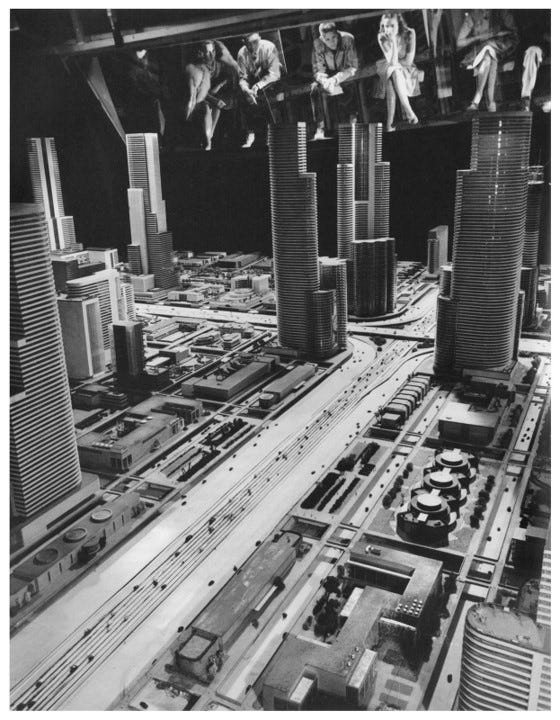

The Suburban Experiment of the 20th century changed all that. It turned community building into an industrial, top-down, managed activity. One current manifestation of it is what I’ve called the Urban Experiment. Some of the same people and forces that built 20th-century suburbia have now shifted to build “urban product,” as they say in the business.

As a person who likes urban communities, I don’t really mind most of the new urban stuff. It speaks to my preferences. I want more people, more services, more everything. I like cities, and I like more people in my city. Most of it looks like crap, and is a version of what Jane Jacobs called “cataclysmic money.” But I’ve come to a peace with it.

The optimist and the trend watcher says urban communities are on the rise, and will keep rising. My city will just keep getting 1% better each year for the next two decades, right?

I am that optimist by nature. I always tend to look on the bright side. My default and preference is to talk about the good things going on in life.

But lately, I see storm clouds brewing that threaten the urban revival. And it's not pretty. It’s a looming Midwestern shelf cloud.

Secondo

The trends that in many ways made the urban revival possible are now feeling very serious stress.

Crime is up in cities. Way up. Many cities now have a feeling of general lawlessness. There seems to be a growing lack of focus on the basics of civilized life. For example, we’re losing the notion that cities should be populated with clean and safe streets for people to walk around in without being hassled. My city is struggling with a surge in property crime, even in “nice” neighborhoods.

Office buildings, the driver of urban employment, have emptied since March of 2020 and are still very slow to fill back up. In fact, it’s likely office employment will never be the same in major downtowns or suburban office complexes. I’ve heard some downtown boosters in very large cities complain, “It feels like the 70s again. It’s empty and scary.”

As I talk to people about my city, they tend to want simple, practical work done to make life better. But our leadership and many activist groups instead seem to be obsessed with big, utopian ideas, policies, and projects. Those big ideas might captivate the imagination, especially of the young, but the overall track record is they nearly always fail spectacularly. That ties to a growing sense on both ends of the political spectrum that everything is rigged in favor of well-connected large corporate entities, and their friends in politics and government bureaucracies.

All this is amplified by the COVID policy response, which has left everyone exhausted and frustrated. Children’s lives have been disrupted beyond anything we’ve seen outside of a war, and the reality is the disruption was worse the closer you lived to an urban center. That’s not something most parents will soon forget.

Anyone who owned a small business in a major city the last few years has deep scars from the experience of forced closures, severe restrictions on hours and service, staffing nightmares, and more. How do those scars manifest themselves in the future? After all, those restrictions didn’t happen everywhere.

Despite all this, there’s a very common attitude of urban arrogance I encounter often. City lovers like me tend not to realize what’s going on in the world beyond our tiny, little bubble. We assume now that progress and revitalization will continue unabated. Because really, who likes the suburbs??? Isn’t it obvious that we have the BEST areas, and what’s the big deal about a little crime, anyway? Get over it, that’s just life. And pay your damn taxes, stop whining.

Dolce

The thing is, people who aren’t diehard urbanists (according to my numbers, about 91.3% of people in our country), simply don’t look at life that way. When normal Americans are scared or concerned, they generally just pick up and move. It’s not often a pleasant subject, plus they might have a house they want to sell for good money, so they don’t like to talk about why. That’s even truer if certain subjects aren’t socially acceptable to discuss, or if they’re worried they’ll pay a price professionally.

Look at the data on how many people have fled big, coastal cities in the last few years. Technology is assisting this change now, with the rise of remote working. As I drive around the periphery of my metro area, I see virtually every small town growing substantially. I see continued suburban expansion. The overwhelming majority of new construction is not in my urban core—it’s on the periphery. I talk with people every day who love the city, but have a growing sense of concern about their safety, about their kids, and about their business prospects. There’s a tension that is hard to ignore. None of us want to leave, but I can read the signs of when people are considering it.

We don’t read much about this in the news. Our news has now become so highly stratified that media outlets just cater to what they think their subscribers want to read or hear. So, the big city newspapers, who have a certain kind of urban audience, don’t want to talk about anything going on in the city in a negative light. They’re happy to highlight anything they perceive as suburban or rural dysfunction, and happy to attack those among their midst who don’t follow a specific political ideology. But they also generally ignore issues for regular people in their own backyard. Speaking of your own problematic issues might make it uncomfortable for friends and allies in positions of power. Big-city interests are so quick to defend anyone on their team they happily make excuses for lousy governing at high prices.

It only took 25 years for American cities to go from 1950 peak to 1975 disaster. That’s a little more than one generation. Do we honestly think it can’t happen again?

Yes, the change in that era also came with a flood of top-down money that made it all worse: urban renewal, highways to the suburbs, subsidized suburban home ownership, and the destruction of urban amenities. And it happened when society was “all in” and excited for the Suburban Experiment.

But arrogance, bad policy, and misplaced priorities today can also create a new flight from the core.

The interest in pro-human places is real, and I still believe it’s long-lasting and durable. But it absolutely can be disrupted by external forces, and, more importantly, doesn’t mean it’s all about big cities or highly populated urban centers.

Many suburban areas are now starting to hit tipping points when it comes to creating their own mini-downtowns. They aren't Paris, but then again, they don't need to be. For a whole lot of people that like a more walkable area, all they really need is a decent coffee shop, a nice park, a couple restaurants and bars, a small grocer, and that's about it. The majority of Americans would be totally OK with that, and don't need to choose between 30 different sushi joints (though that sounds great to me). Our urban culture in most of the country is still very young. We don’t have 1,000-year-old cities, like Europe and Asia. Expectations are much lower here for what qualifies as urban life.

But Americans do have high expectations when it comes to the basics of living in a community. If we start to revisit the urban dysfunction of the 1970s, with high crime, lawlessness, and calcified bureaucracies that are openly hostile to small business, we will in fact see a new exodus to the suburbs and exurbs.

Digestivo

With every action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction. Policy makers almost never consider the consequences of their measures beyond a simple, immediate action. When the interstate system was conceived in the U.S., it was often urban business boosters that lobbied for interstates to come right into their downtowns instead of circling well around the periphery. They thought it would better facilitate more people coming in to do business, and enhance their cities. In their arrogance, they never imagined a scenario where the downtown wouldn’t be the primary place to do business.

In fact, urban freeway systems did the opposite—they enabled a world where people didn’t need to be downtown, at all. New communities and new job centers sprung up much farther away. People left the city and didn’t return. Most of our downtowns suffered tremendously, as a result.

It's impossible right now to know what consequences will come from three years of the COVID policy response. But I am certain it’s not what we see with any of the common wisdom in today’s discussions. Too many people have experienced major disruptions in their lives beyond just illness: a business closure, school closures and disruption with their kids, financial pain, social trauma, and much more. Too many wheels have been set in motion that will roll on for years to come. I’m not entirely sure we’ve even begun to see the impacts yet.

None of us want to talk about this anymore. Most people want to move on with their lives. But the legacy of what has happened, I believe, will resonate for many, many years into the future. We are going to see changes that surprise all of us, in all aspects of politics and culture. If I had to make a wager right now, I’d put money on the likelihood that a whole host of late 20th-century cultural trends are going to reverse over the next decade or two. Some of this you may already be noticing. Some won’t likely really be evident for many years from now. In my little professional world, I see new blowback to the urban revival and the critique of suburban sprawl, and it has me concerned.

Nothing is inevitable.

These are my observations. Your mileage may vary.

I'm a city person. I love my city; I love urban life. But I’m also human, a father, and a realist. It’s not at all impossible to see a scenario where my family and I could say, “enough—let’s go somewhere else.” I have kids to think about, and I put a very high priority on normalcy and safety for them. If I can imagine those scenarios, how many others have done so who aren’t at all committed to the city?

Watch out, fellow urbanists. Let's not sow the seeds of our own demise. If we want our places to continue to thrive, we need to focus on what matters for normal people. And, it’s really not that complicated: safety and security, cleanliness, doing the basics really well, and focusing on what’s best for children. Let’s ditch the never-ending quest for utopia, and focus on projects and policies that have shown to work for humans throughout the centuries. Let’s stop reflexively defending our politicians and the administrative apparatus, and demand better. Much better.

And just for a while, let’s set aside the smugness and arrogance that’s so common with lovers of big cities. It’s a big world out there, full of lots of great people that love to live very different lives. We don’t have the only way.

Cities can be so wonderful for so many people. Let’s not screw this up.

[[divider]]

This article was originally published on Kevin Klinkenberg’s blog, The Messy City. It is shared here with permission. All images for this piece were provided by the author, unless otherwise indicated.