Award-Winning Show "Beef" Offers a Subtle Commentary on Auto-Oriented Design

We’ve all been there: sitting behind a distracted driver who doesn’t realize the light has turned green. This was me a few weeks ago, sitting behind a pickup truck anxious to get my errands done. I finally tapped the horn to nudge the driver on. His hand flashed up to the rearview mirror and I worked hard not to be mad at him for his rude gesture.

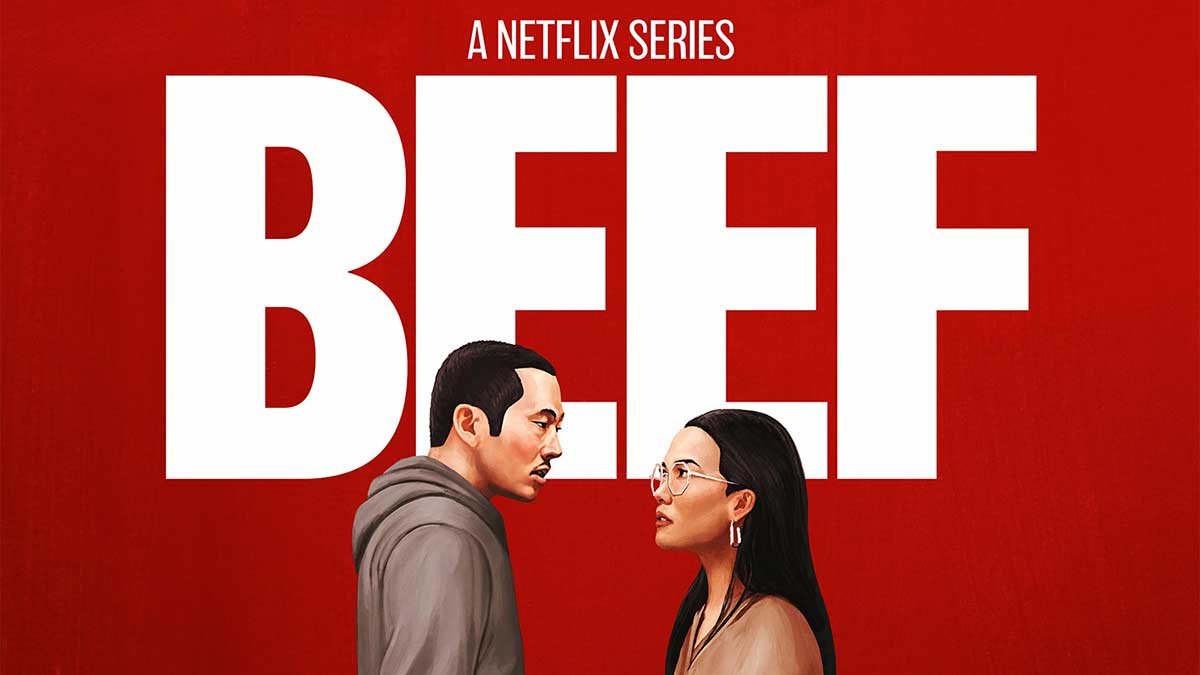

This common experience is what Lee Sung Jin explores in Beef, his brilliant, award-winning, and highly bingeable Neftlix original starring Steven Yeun, Ali Wong, Young Mazino, and Joseph Lee. I suggested it to my husband one evening and a few moments in, we found ourselves thoroughly captivated.

To friends, I have described Beef as a morality tale centered on two characters who, due to a combination of bad choices and societal pressures, are pretty dang angry. Their anger explodes during a road rage incident which, in turn, sparks a series of vengeful choices, lies, and more deceptive choices to cover those lies…eventually causing a series of events that spiral out of control. Lee Sung Jin creates a story that is equally unbelievable and entirely relatable, moved forward by characters who take amusing stereotypes (the overachieving entrepreneurial mom, the second-generation Korean American immigrant trying to help his parents, the earnest Korean pastor…just to name a few) and give them so much heart that you feel torn between laughing and crying.

One could argue the show is a commentary on the dissatisfaction of our consumerist culture: “everything fades,” is a common refrain. Or perhaps it’s a story about the importance of telling the truth, most importantly, to one’s self. Or perhaps it’s a story about class tensions, told partially through the lens of the immigrant experience.

It might be all of these stories…but let’s not forget what sets the entire show in motion: an incident of road rage. Based on a true story, Beef starts with the extremely relatable situation of one driver protesting another car backing out of a space too fast, nearly causing a collision. The classic angry gestures are exchanged, sparking a dramatic high-speed chase through the city and antagonistic driving maneuvers that escalate already sky-high tempers. Initially left unresolved, the social clash picks up again once Danny (Steven Yeun) tracks down the residence of the other driver (Ali Wong), setting off a feud that nearly destroys them both.

The triggering event in that parking lot might not seem significant in light of all the other sub-narratives and situations that unfold, but it’s actually quite critical to the story, because Beef is really about alienation. The protagonists are alienated from their families, from friends, and, most critically, from themselves.

“The show is about separateness,” Lee Sung Jin explained in a behind-the-scenes video. “We all have our own thoughts in our head that can be very isolating and lonely.” There’s not a single person in the story to whom the two protagonists are capable of telling the truth…until it’s too late. What better way to tell a story about alienation than to center it on the automobile, one of the most alienating devices of modern life?

Wait! One might protest. Cars help us be more connected to each other. Like smartphones, yes, this is part of the promise. They do, indeed, have that potential. But like smartphones, this enhanced connectedness is only part of the story. The other part of the story is the effect that cars have on how we perceive time and space but, more importantly, on how we perceive other people. Watch carefully a big-budget car commercial these days and you’ll see an implied promise of dominance over and freedom from nature. You’ll also see an implied promise of freedom from other people. Just look at the footage of empty, winding roads along stunning vistas. “You’ll not have to deal with other people,” the message goes. “Or at the very least, you’ll only have to be around the ones you like.”

Not only do these messages constitute frustratingly broken promises, but they don’t tell the truth. The limited nature of drivable space combined with the overabundance of cars mean few of us have the luxury of cruising down scenic pathways with no other driver in sight. Most of us not only have to drive because our cities are built to be auto centric and fail to offer other transit options, but we also have to deal with traffic and negotiate with other drivers. But it’s not real negotiation because, as Beef reminds us, we’re not really seeing the “other driver” as a person. The drivers never see each other during the entire incident. And, like them, we literally can’t see each other at all when we’re in our automobiles. We can’t engage with each other as real human beings, only as obstacles.

In Beef, this lack of visibility is a central part of what moves the story forward. By the time Amy and Danny are face to face, Danny realizes his assumption that the “other driver” was male is false. But he has made a commitment to vengeance and it’s too late to turn back. He and Amy are so blinded by their emotions that they can’t empathize with each other. Mutual understanding doesn’t come until the near-end of the show.

This dehumanization perhaps becomes most clear in moments of road rage. Like my story about the distracted driver, I’m sure we can all relate to the sudden, hot anger that flows through our bodies the moment we are abruptly cut off, tailgated, or held back at a green light by another driver. I’m sure we can relate to the way such incidents immediately tempt us to vilify that person. We don’t know anything about them or their lives, but in the blink of an eye, none of that matters…they have become our arch-enemy.

This inordinate rage is what makes Beef so funny, so relatable and so tragic. And in this sense, I think it’s a warning about the way technologies can change us and how we see each other. In his book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, Neil Postman warned about “the Faustian bargain” behind television, making the case that every tool, every innovation, every piece of technology that we allow into our lives will ask something of us that we might not actually want to give up: our attention, our patience, our empathy.

I don’t think Lee Sung Jin was setting out to make a commentary on car culture with the show, but I think the commentary is there if we know how to look for it. Just as for Danny and Amy it takes an over-the-top encounter to shake them out of their self-delusion and damaging relational patterns, maybe it takes an over-the-top story to get us to think more seriously about the tools we are so accustomed to living with that isolate us from each other.

Tiffany Owens Reed is the host of The Bottom-Up Revolution podcast. A graduate of The King's College and former journalist, she is a New Yorker at heart, currently living in Texas. In addition to writing for Strong Towns and freelancing as a project manager, she reads, writes, and curates content for Cities Decoded, an educational platform designed to help ordinary people understand cities. Explore free resources here and follow her on Instagram @citiesdecoded.