Playing the Blame Game Won’t Make Our Roads Safer

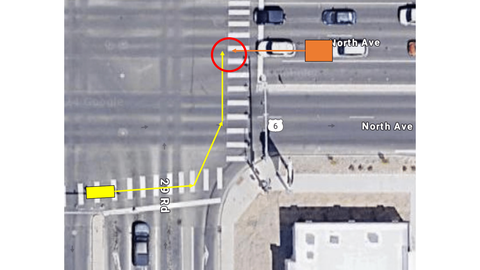

Google Street View shows an individual using a wheelchair to cross a dangerous intersection in Grand Junction, CO—the site of a recent Crash Analysis Studio session.

"Why are they adding more pedestrian amenities here? It just doesn't make sense for the road they designed,” Strong Towns Director of Community Action Edward Erfurt asked when examining the site of a crash in Grand Junction, Colorado.

Erfurt wasn’t suggesting that North Avenue should lose its sidewalks and crosswalks. Instead, like many of the country’s most dangerous roads, North Avenue needs to “decide” whether it wants to prioritize foot traffic or vehicular throughput, whether it wants to be a neighborhood street or a highway. “We say this every time, but you can’t have both.”

At least, you can’t have both without routinely endangering people’s lives. Around 8:53 p.m. October 8, 2023, Joseph E was bicycling along North Avenue where it intersects with 29 Road when Trisha L struck him, landing Joseph in the hospital with serious injuries. At this intersection, North Avenue stretches six lanes with two dedicated turn lanes for westbound traffic. Trisha was in the inner westbound lane, driving forward when she had the green light to do so, and operating approximately 10 miles below the posted speed limit of 40 mph. In other words, the driver was operating their vehicle entirely lawfully. Yet, a person was nearly killed and the driver’s car totaled.

“Even when everyone is doing what is expected of them,” Strong Towns President Chuck Marohn noted, “in the transportation system that we’ve designed, there will be a base level of trauma, death, and violence.”

When news broke of the crash, police and media were quick to note the bicycle rider’s “unlawful” behavior. Joseph was neither wearing a helmet nor riding in a bike lane. According to the police report, when he was turning, Joseph was also riding a few feet west of the crosswalk of the signalized intersection. It’s true that the North Avenue on which Joseph was riding is devoid of any dedicated lanes for bicycles, though there is a lane on 29 Road that would deposit a cyclist onto that exact cross section of North Avenue, consistent with the mixed messaging Erfurt underscored earlier.

For Marohn, whether Joseph was acting entirely within the expectations of the law is somewhat irrelevant. “If you’re walking or biking in an auto-dominated environment, you are always rolling the dice,” he said. “What we need to be doing is making those odds work in our favor. Right now, they’re not.”

While Trisha was not speeding at the time of the crash, a speed study conducted illustrates that exceeding the posted speed limit is a routine problem on North Avenue. The road is undoubtedly an unpopular and unattractive route for people traveling by foot or bike—it’s a stroad. Yet as the main thoroughfare for a constellation of residential subdivisions, several schools—including Bookcliff Middle School, Nisley Elementary School, and Colorado Mesa University—as well as a handful of parks, it’s still accessed by those means, however unideal. Even a casual browse through Google’s Street View showcases people traveling by foot, bicycle, and wheelchair on the same intersection that nearly killed Joseph E.

Media and law enforcement’s preoccupation with fault, in this case the cyclist’s fault for navigating a space that fundamentally was unwelcoming, does a disservice to anyone wanting to see a reduction in crashes. “If we’re interested in less crashes, less death on our roads, we should be trying to reduce the margin of error,” Marohn explained. “Placing blame on an individual won’t do that.”

In a place like Hoboken, New Jersey, for example, where speeds are not only limited to 20 mph throughout the city by law, but also reinforced through design choices like daylighting, collisions are a rare occurrence and deaths nonexistent in the last seven years.

The city’s traffic is like that of any other place in the country: oversized delivery trucks mingle with sedans, and passenger SUVs share the streets with cyclists, pedestrians, and school buses. Some traffic is local, other traffic is merely passing through. Yet, this mile-long city of nearly 60,000 hasn’t had a single traffic death since 2018 because it’s eliminated the types of design choices that increase the risks, however “lawfully” motorists, pedestrians, or cyclists are behaving.

When crowds of kids spill out onto the streets after school, tipsy bar patrons walk home late at night, or people walking are “distracted” (as Pennsylvania’s Department of Transportation recently put it in a Public Service Announcement) by music, motorists are given enough visibility and time to react appropriately. Hoboken’s commitments illustrate an admission that humans will make mistakes. And in doing so, it ensured that, unlike in so many other places in the country, the cost of making a mistake wouldn’t have to be one’s life.

Strong Towns will be analyzing the crash that took place in Grand Junction, Colorado on March 22, 2024, as part of the Crash Analysis Studio. You can register for and attend the session here.

Asia (pronounced “ah-sha”) Mieleszko serves as a Staff Writer for Strong Towns. A dilettante urbanist since adolescence, she's excited to convert a lifetime of ad-hoc volunteerism into a career. Her unconventional background includes directing a Ukrainian folk choir, pioneering synaesthetic performances, photographing festivals, designing websites, teaching, and ghostwriting. She can be found wherever Wi-Fi is reliable, typically along Amtrak's Northeast Corridor.