Federal transportation programs are intended to support safety, maintenance, and mobility. In practice, they often do the opposite.

While some federal programs can fund maintenance, the most politically attractive dollars — especially those tied to discretionary grants — tend to support expansion. State and local governments, often struggling to maintain their existing infrastructure, have learned to repackage expansion projects as safety or maintenance upgrades to make them both palatable to the public and eligible for federal support.

This is both a funding distortion and a political narrative strategy. This dynamic has fueled a nationwide pattern of overbuilt infrastructure that cities and states cannot afford to maintain.

Rhode Island provides a clear example of this pattern.

A State in Decline

Rhode Island’s roads and bridges are falling apart. The Ocean State ranks dead last in bridge condition, with 22% of its 1,162 bridges deemed structurally deficient. Over 80% of the state's non-interstate National Highway System is in fair or poor condition. According to a 2020 report card by the American Society of Civil Engineers, this deterioration costs Rhode Island drivers an estimated $620 million per year in additional vehicle expenses.

For residents, the tradeoff is obvious and frustrating: despite paying taxes, tolls, and supporting transportation initiatives, they are not getting basic maintenance in return. They sit in traffic caused by emergency road repairs. They detour around weight-restricted bridges. They endure damage to their vehicles from potholes, crumbling shoulders, and uneven surfaces.

And they watch as their state government, instead of catching up on long-delayed repairs, continues to pursue large, costly projects that only add to the backlog. These everyday experiences reinforce the sense that the system is failing them, not just functionally but also financially.

That growing frustration reached a new peak in 2022 when, instead of triaging their maintenance backlog, state officials celebrated the groundbreaking of an $85 million project, an expansion project that will only stretch their maintenance resources all the more.

The Cranston Canyon Project

The Cranston Canyon Project is framed by officials as a rehabilitation effort, a fix for a dangerous, outdated corridor on Route 295, which they claim suffers from congestion and outdated design.

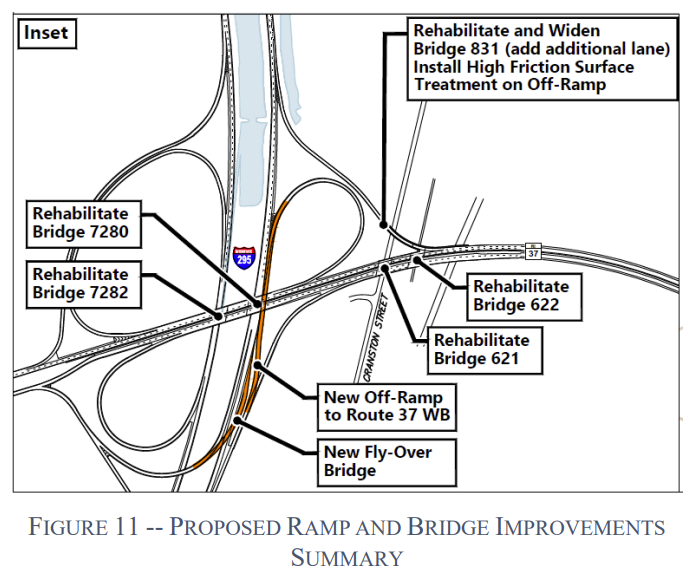

The full project spans roughly five miles between the bridges over Route 2 and those near Plainfield Pike in Cranston. It includes rebuilding two bridges, widening the corridor to add a third travel lane in each direction, and reworking entrance and exit ramps.

While the state's press release emphasizes safety and rehabilitation, the project is fundamentally an expansion initiative. Of the $78 million in non-administrative costs, $41.4 million — 53% — is going to widening and expansion. It will create new infrastructure that the state will have to maintain for decades, adding to an already unsustainable burden.

This is a prime example of how federal transportation dollars distort decision-making. The project received a $21 million federal BUILD grant. These funds cover approximately half the cost of the expansion, not the maintenance. Rhode Island taxpayers are covering the rest: the full cost of bridge repairs, the administrative overhead, and the other half of the expansion.

When federal grants like BUILD, TIGER, or RAISE are dangled, states have every incentive to craft projects that appear shovel-ready and safety-oriented but are, in practice, expansion schemes. These grants come with a local match requirement, pulling even more state and municipal dollars away from basic repair work to chase federal money.

The result is a larger, more expensive transportation system, one that Rhode Island — which is already drowning in maintenance liabilities — will be responsible for maintaining long after the federal dollars are gone. The new lanes, bridges, and interchanges may bring short-term visibility and political celebration, but they come with a long-term price tag. Every mile of new roadway represents decades of future costs for resurfacing, snow removal, inspections, and eventual reconstruction. These are costs the state has no credible plan to fund.

Conclusion: A Broken Funding Model

The Cranston Canyon Project is not an isolated mistake. It reflects the deeper structural failure of America’s approach to infrastructure. The Federal Highway Trust Fund, originally designed to build the Interstate System, is insolvent. In its place, we have a system of federal programs that reward expansion over maintenance, prioritize complex projects over practical ones, and incentivize poor outcomes at every level.

States, acting rationally within a broken system, often rebrand expansion projects as safety or maintenance efforts to qualify for federal funding. This practice allows them to secure grants and meet program requirements, even when the underlying projects will only deepen their maintenance obligations. The result is a transportation system that grows larger and more expensive, even as the ability to maintain it continues to erode.

This disconnect primarily stems from the mismatch between what local communities need and what federal programs are designed to fund. Local infrastructure challenges are nuanced and complex — sidewalk gaps, dangerous crossings, deteriorating bridges — while federal programs operate on a scale that favors simplicity and visibility.

Programs like TIGER, BUILD, and RAISE are attempts to reconcile this gap, but they remain fundamentally top-down in design. A more resilient system would focus federal investment on the simple, essential things it can do well — like supporting national mobility — and leave the complexity of local infrastructure to the governments closest to the ground.

Rhode Island didn’t need an $85 million expansion. It needed routine care. Until we confront the incentives embedded in federal transportation spending, states will continue to build what they can’t afford to maintain.

The result isn’t safety. It isn’t mobility. It’s decay.