The Buttonhook Isn’t Designed To Solve Baxter’s Mythical Congestion

When I wrote about the proposed “buttonhook” interchange at the intersection of Highways 371 and 210 in Baxter ("Six Roundabouts to Nowhere"), I expected some pushback from locals, people who live here in my community. What I maybe didn’t expect was how many people would say the same thing in response: But the traffic is terrible. We have to do something.

That’s a fair objection. It deserves a fair answer.

This is the first in a short series of follow-up columns responding to the local feedback I received. Three core themes came up again and again: (1) traffic congestion, (2) safety concerns, and (3) support for local business. Each will get its own response.

Let’s start with congestion.

The 210/371 intersection has been described by MnDOT as “the busiest intersection in northern Minnesota.” That may well be true, but it’s like saying it’s the biggest fish in a goldfish bowl. This same intersection wouldn’t crack the top 100 busiest in the Twin Cities metro. It wouldn’t make the traffic report in Phoenix. It wouldn’t register as a slowdown in Atlanta or Los Angeles.

Yes, traffic here backs up, especially on summer weekends when lake visitors pour in. It can feel frustrating, especially for those of us who remember how easy it was to get through Baxter 20 years ago. I’ve lived here most of my life. I get it.

But let’s be honest: This isn’t real congestion. Not in any meaningful sense of the word. What we’re experiencing is the frequent breakdown of a fragile corridor, one designed incoherently for speed and access at the same time. Apply the slightest pressure, and it fails. The problem isn’t the number of cars. It’s the sheer number of conflict points — signals, access points, turning movements — that create delays, crashes, and the perception of congestion.

We’re preparing to spend $58 million on a traffic engineer’s fever dream they’re calling the buttonhook, ostensibly to “fix” a congestion problem that barely exists. Before we do that, we should at least properly understand what it is we claim we’re trying to fix.

What’s Actually Causing the Congestion We Perceive

We don’t have the volume of traffic in Baxter to justify a six-roundabout interchange wrapped around 30-foot retaining walls. What we have is a stroad design that starts to fall apart any time things get even a little bit busy.

A stroad is what happens when we try to build something that’s both a high-speed road and a low-speed street at the same time. It is a design that promises the efficiency of a road and the access of a street, but delivers neither. It’s wide and fast enough to encourage fast-moving through traffic, but full of access points, turn lanes, and signals that constantly interrupt that flow. It’s lined with destinations, but so hostile and unsafe that people can only reach them by car. The result is a corridor that feels congested at low volumes and becomes downright unusable whenever there’s a spike in demand.

This corridor wasn’t built to be resilient. It was built for a different era, one where maximizing access to big-box stores and fast-food drive-thrus was treated as the transportation goal. So now we have a high-speed highway, loaded with turning movements, crisscrossed by left turns, right turns, traffic signals, and access points. It’s not congestion we’re experiencing. It’s conflict.

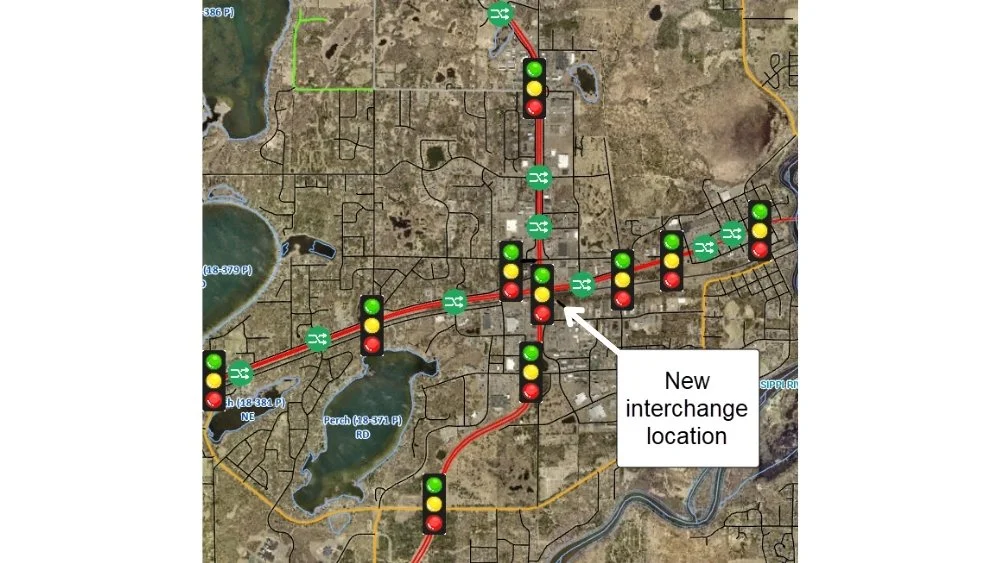

Here are all the intersections within what locals think of as the “congested” part of this corridor. Some are full traffic signals, some are left crossovers, and some are right-in/right-out. Count them. There are 10 fully signalized intersections — all of them creating congestion, especially during peak times — and 9 crossover or right-in/right-out intersections, the major source of tension and conflict in this area.

These access points cause backups. They create the conflict points. They increase the danger and the tension experienced by anyone who drives this corridor. If this project were truly about reducing congestion, the very first thing the engineers would do would be to remove the access features causing the congestion (the green icons).

And yet, this $58 million project doesn’t eliminate them. It doubles down on them, codifying every one of these random access points as a permanent feature of the corridor. We remove the two signals in the middle, which is going to do next to nothing for traffic congestion.

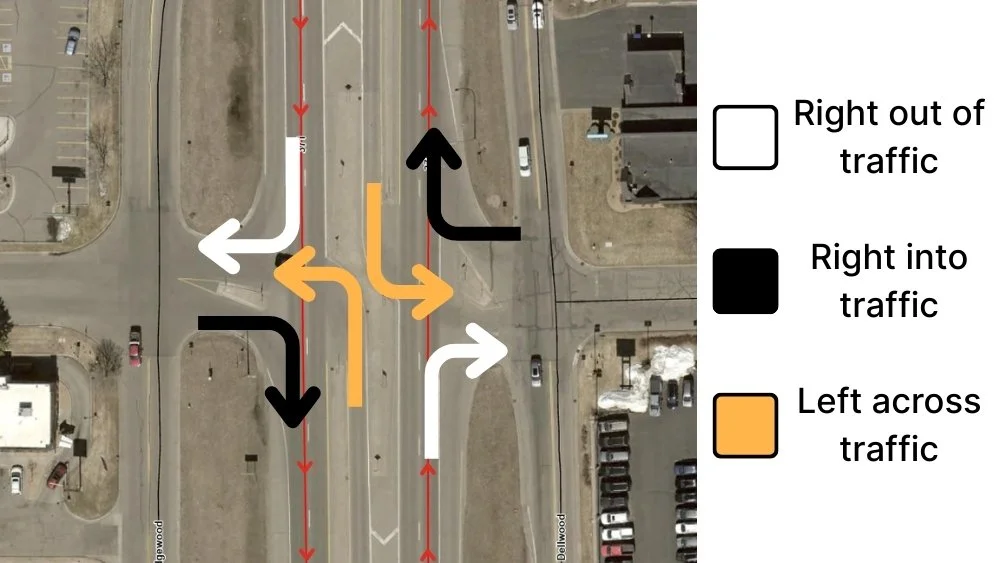

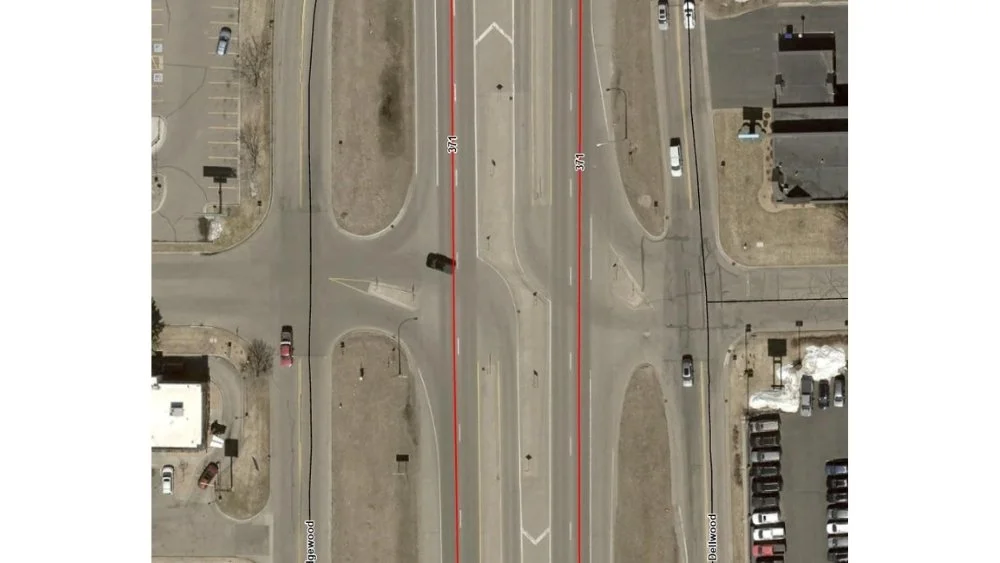

Let’s take just one example, the most egregious. Here’s the ¾ intersection at Design Road. In both directions, a driver can turn right out of traffic, turn right into traffic, or turn left across traffic. This intersection has been rebuilt a number of times because of the high number of violent crashes. The left crossover, in particular, is the most dangerous turning movement a driver can make. That is especially true at highway speeds.

My next column will be about safety, so I’ll withhold additional commentary on just how dangerous this is and focus here only on congestion. Why is this intersection here? Why wasn’t it closed decades ago? What function does it serve?

And here is where locals — those complaining about the high levels of congestion they experience here — know something that the rest of you reading this are only learning now. This particular ¾ access point and all its congestion-causing conflicts sit less than 1,000 feet away from a fully signalized intersection.

Someone driving north on Highway 371, a corridor with highway speeds, has the option to turn at the fully signalized intersection at Excelsior Drive, or travel 1,000 feet farther — a distance that takes seconds — to make the exact same turn. Why?

Once the buttonhook is complete, the turn at Excelsior will be an exit to a roundabout. And yet, there is no proposal to remove the second, totally redundant, congestion-causing intersection. If congestion is the problem, why have these conflict points at all?

Why? Because this project isn’t about reducing congestion. It never has been. And neither have any of the highway “improvement” projects in this corridor over the years. Congestion is a story we tell ourselves — “the busiest intersection in northern Minnesota, ya know” — but it’s just a sales pitch.

We aren’t serious about reducing congestion. Not in the least.

Here’s What It Would Mean to Reduce Congestion

If we were serious about reducing congestion in this corridor, we would start by making the road function like a road. That means designing it to move vehicles efficiently, not trying to move them quickly and give them easy, unlimited access to adjacent businesses at the same time.

Congestion on a true road happens when there is more traffic volume than the road can handle. The way to improve flow is to remove the things that slow vehicles down — traffic signals, access points, and turning movements across lanes of traffic. You can’t preserve every entrance and every signal in the name of “access” and still expect smooth traffic flow. It doesn’t work that way.

Highway 371 is a state highway. Highway 210 is a state highway. Their function is to move vehicles quickly from one place to another. If we’re truly solving for congestion, we have to prioritize that function.

On Highway 371, the fastest, cheapest, and most effective way to improve traffic flow would be to:

Build the single-point urban interchange design that MnDOT already proposed.

Eliminate the intersection at Excelsior Drive.

Close redundant access points like Design Road and other unsignalized intersections.

Remove the left crossovers that create unpredictable stops and dangerous weaving.

Space out full intersections far enough that traffic can stabilize between them.

Replace signals with continuous-flow designs where possible.

The key insight is this: A corridor can be either a road or a street, but not both at the same time. A road moves vehicles efficiently between places. A street provides access to destinations. The moment you try to make one corridor do both jobs, you guarantee congestion, along with crashes and ridiculously high costs.

If MnDOT’s true goal was to address congestion, this project would begin with a hard choice: Either make Highway 371 a road and remove most of the access, or turn it into a street and accept slower speeds. What we have now — a high-speed corridor riddled with turning conflicts — is the worst of both worlds.

Sadly, that’s typical for the Minnesota Development of Targets, where “improvements” are about serving big boxes and national franchises, not fulfilling their actual role of providing efficient transportation. And if you want to see just how serious they are about subsidizing one approach to development over another, look at what the exact same agency is doing next door in Brainerd.

Washington Street or Highway 210?

MnDOT is willing to compromise traffic flow — and spend $58 million in the process — to support big box stores and national chains in Baxter. When it comes to corporate subsidies on the highway strip, fighting congestion is part of the sales brochure, but there is no real commitment to it. Your time and tax dollars will be freely wasted if it helps justify keeping every access point and turning movement that those retailers want to maintain.

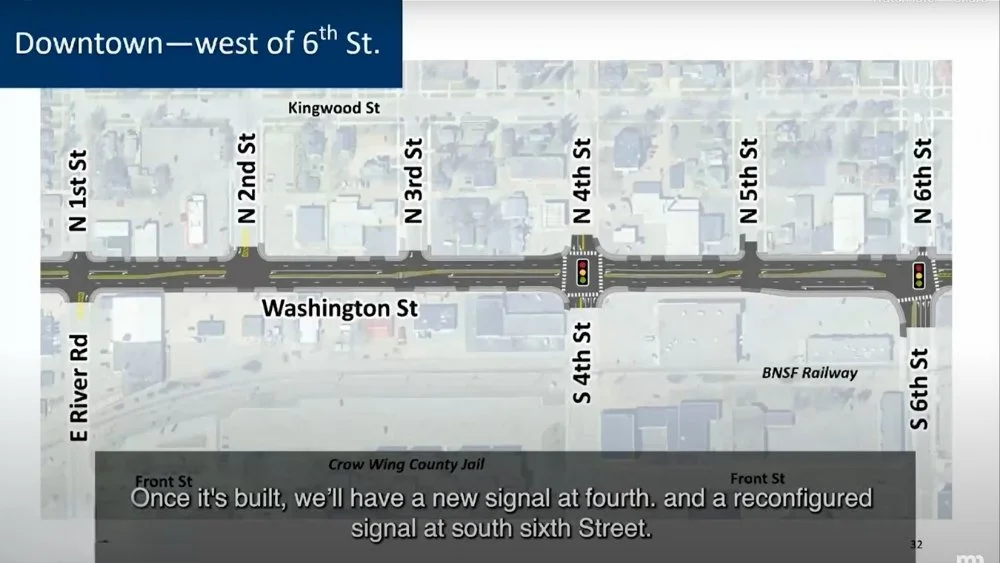

But once it gets into the historic city of Brainerd, MnDOT adopts the opposite approach. Washington Street — as residents know it — is Highway 210 to MnDOT. The Washington Street project, planned for a similar timeframe as the buttonhook, prioritizes moving traffic through the city over any business concerns. The plan removes parking, restricts turning movements, and forces long-standing businesses along the corridor to relocate their main entrances to the alley.

(Source: MnDOT.)

In downtown Brainerd, we can’t slow traffic for nine blocks. We must “fight congestion” and improve traffic flow, even in the complexity of a historic district full of people biking, people walking, and small businesses barely hanging on. Yet, on the Baxter highway strip, we will embrace congestion — and bear great financial burden — to provide access to national chain retailers.

Why the difference?

In downtown Brainerd, there are no corporate chains. No Target. No Costco. No Home Depot. No Fleet Farm. Just struggling small businesses, the kind nobody in St. Paul is lobbying for. The kind of shops nobody in the region cares much about, either.

This is a broken system. In a future column, I’m going to show why this is economically backward, but today’s column is just about congestion. Merely wasted time. In my next column, before I get to the economics of development, I’ll address the safety issues.

If wasting time is bad, wasting lives is so much worse.

This post is made possible by Strong Towns members. Click here to learn more about membership.

Charles Marohn (known as “Chuck” to friends and colleagues) is the founder and president of Strong Towns and the bestselling author of “Escaping the Housing Trap: The Strong Towns Response to the Housing Crisis.” With decades of experience as a land use planner and civil engineer, Marohn is on a mission to help cities and towns become stronger and more prosperous. He spreads the Strong Towns message through in-person presentations, the Strong Towns Podcast, and his books and articles. In recognition of his efforts and impact, Planetizen named him one of the 15 Most Influential Urbanists of all time in 2017 and 2023.