Los Angeles is broke.

The city that once defined postwar prosperity — where wide streets, endless subdivisions, and freeways to the horizon promised a future of limitless growth — has been dealing with a $1 billion budget shortfall. City leaders are cutting services, delaying maintenance, and quietly floated the possibility of layoffs. The rhetoric is familiar: revenues came in below projections, costs rose faster than expected, the economy is uncertain. But the story here isn’t about a bad year. It’s about a bad model.

Los Angeles didn’t mismanage its way into this hole. It built its way here.

For decades, LA’s prosperity has been an illusion of motion. Each wave of development — another subdivision, another mega-project, another round of borrowing — produced a temporary surge in cash flow. The city paved more streets, expanded more utilities, and added more infrastructure than it could ever maintain. To cover the gap, it relied on new growth to pay for old promises. That worked for a while. Then it didn’t.

Former Los Angeles Deputy Mayor Rick Cole recently summed it up with characteristic clarity: “Beneath the broken sidewalks is a broken system.”

After 40 years inside City Hall — from his early days under Councilmember Richard Alatorre to his final role as Chief Deputy Controller — Cole told the Council he’s never been more alarmed about the city’s future. He ticked through the list: a state of emergency on homelessness, a crumbling infrastructure, grotesque inequality, and what he called “a failing public trust in government’s ability to confront these existential challenges.”

“L.A. is not designed to work,” Cole said, describing how the city’s original charter dispersed authority to prevent corruption but also diffused accountability. That structure made sense a century ago when growth seemed infinite, but today it leaves Los Angeles unable to adapt. “For decades,” he said, “this city has ridden the cycles of boom and bust, making short-term decisions with long-term consequences.”

Controller Kenneth Mejia put numbers to that diagnosis just days later. Speaking after the City Council voted to approve a $5.5 billion expansion of the Convention Center — a project that will leave taxpayers making debt service payments until 2056 — Mejia warned, “We are still on the hook to find an additional $104 million each year for the next 30 years. I do not know where we’re going to find it.”

In his briefing, Mejia described a city that keeps “spending over budget, overestimating revenues, and depleting our reserve fund,” down from $648 million to just $300 million in two years. Departments are being hollowed out through hiring freezes, furloughs, and layoffs while basic services crumble. “You can just see how bad everything is,” he said, listing broken roads, dark streetlights, decaying parks, and overwhelmed shelters. “It mind boggles me how the city is handling its finances.”

Between Cole’s farewell and Mejia’s report, the story converges: Los Angeles is not simply broke; it’s structurally insolvent. The political system is too fragmented to respond, the financial system too addicted to growth to sustain itself, and the civic infrastructure too worn down to carry the load.

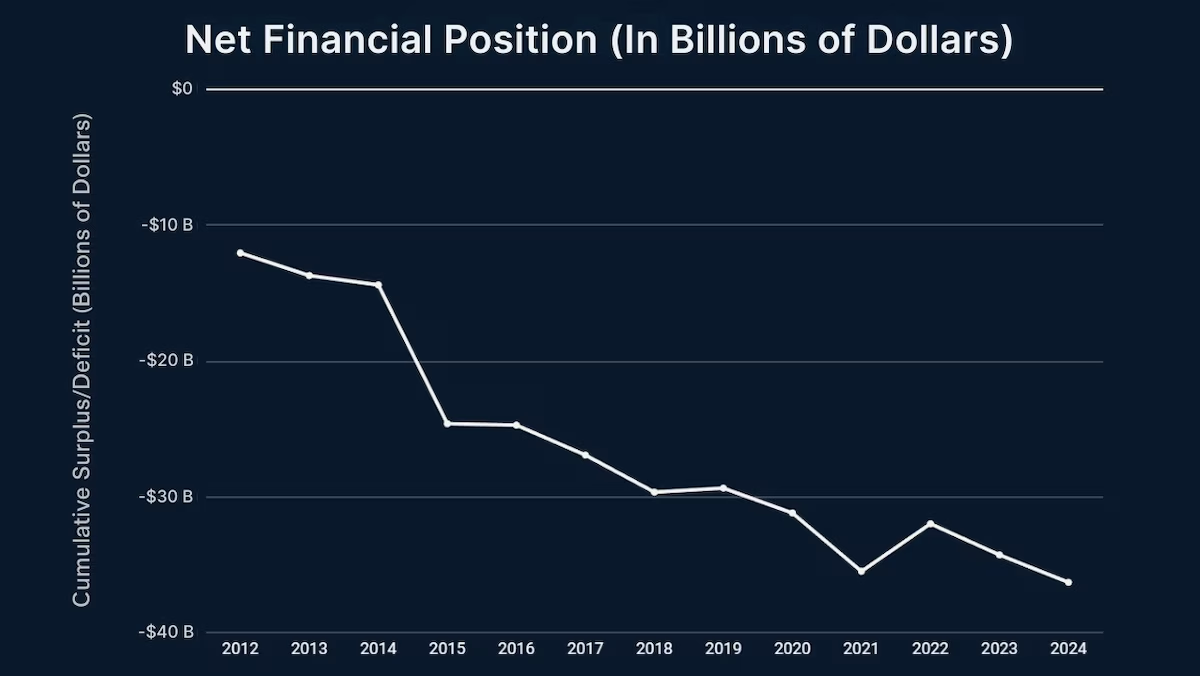

This might sound like alarmism, but the city’s own books tell the same story, just in a different language. When you look at Los Angeles through the Strong Towns Finance Decoder, the pattern is unmistakable. The city’s Net Financial Position — its total financial assets minus its total liabilities — is deeply negative. That figure represents past spending that must now be paid with future revenue. Before the city even begins to deal with today’s problems, it’s already carrying the weight of yesterday’s promises.

The trend is also unmistakable. The recent cash shortfalls look enormous, but they are just another small decline added to the nearly $40B in accumulated deficits Los Angeles has burdened itself with. (Note: This is actually worse than NYC, which surprised even me, although it shouldn’t have. Los Angeles has 55% more land area and less than half the population of NYC. It is just inherently more fragile, a reality time is destined to increasingly expose.)

This financial noose is what happens when a system is designed to chase growth but ignore productivity. For decades, Los Angeles expanded its physical footprint faster than its financial base. Every new subdivision, every capital project, every deferred maintenance decision created the illusion of motion and progress, even as the balance sheet fell further behind. The underlying bet was simple: If we just keep running fast enough, we can stay ahead of it all.

But the treadmill has stopped. Or, at least, it can’t run fast enough to keep up anymore. It’s just not possible.

The backlog of basic maintenance — streets, sidewalks, pipes, buildings — now runs into the tens of billions. That’s not theoretical debt; it’s a physical reality that shows up in potholes, outages, and service failures. Each year, the gap widens between what the city owns and what it can afford to maintain.

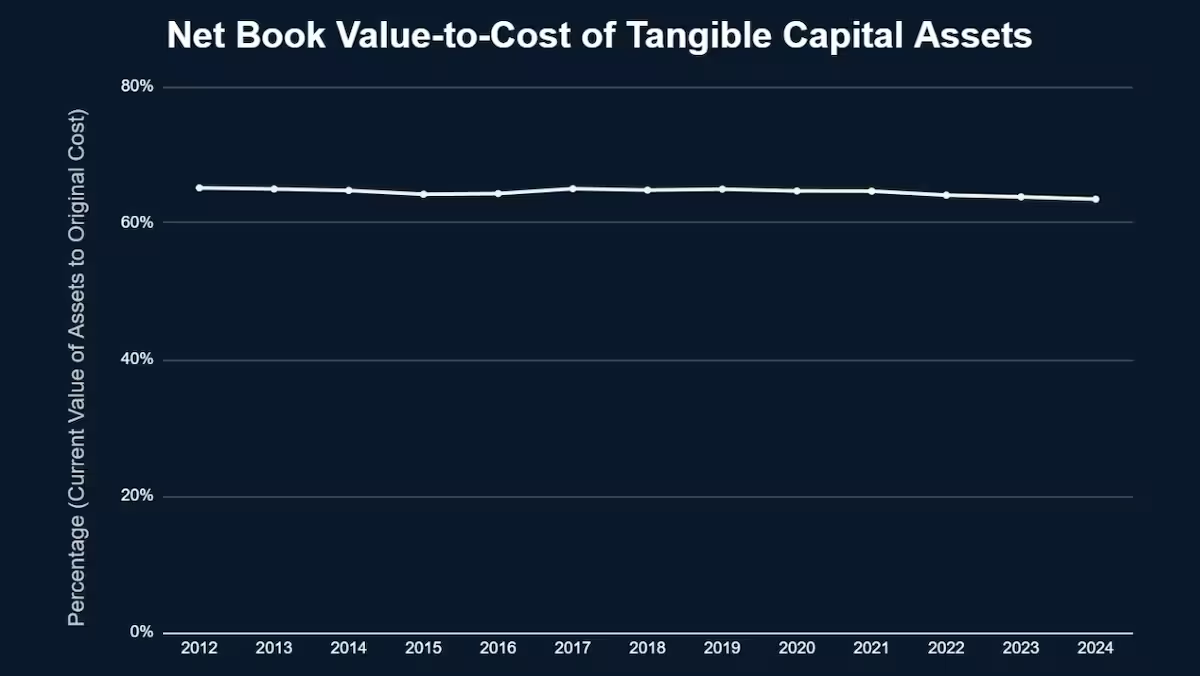

The Finance Decoder shows Los Angeles holding steady on infrastructure maintenance, but at a dangerously high level of depletion. And that steadiness is misleading. New projects — like a $5.5 billion convention center expansion — add to the city’s Tangible Capital Assets in a way that hides decline. A lot of roads, pipes, and sidewalks can fall apart without appearing in the financial records if something shiny and expensive gets added to the balance sheet.

None of this is unique to Los Angeles. It is the California model. Cities across the state were built on the same premise: that growth could pay for itself. When that began to get expensive for taxpayers, Proposition 13 — limiting property tax increases to rates far below appreciation or even inflation — was the quick fix. It keeps taxes low for those already in place, but increasingly burdens newcomers while locking local governments into dependence on one-time revenues — sales taxes, fees, and state transfers — and discouraging the kind of incremental reinvestment that sustains long-term productivity.

The result is a local finance system dependent on new development but structurally incapable of maintaining what’s already been built. There’s nothing for the municipal corporation known as the City of Los Angeles to gain financially from simply being a responsible, competent government that provides stable services for its citizens and businesses. In fact, quite the opposite.

The way Los Angeles — and cities like it across California and most of the rest of North America — make financial ends meet is by shorting basic maintenance and quality-of-life services in pursuit of the revenue that comes from the flashy and the new. That’s a horrible business model, but the Suburban Experiment is, quite simply, a dumb way to build cities.

Los Angeles isn’t an outlier. It’s a preview.

Every city that grew up in the Suburban Experiment is built on the same fragile foundation: rapid expansion financed by promises the future would somehow cover the cost. For a long time, it seemed to work. The suburbs filled, revenues climbed, and the illusion of prosperity kept everyone running. But you can only stretch a system so far before it stops bouncing back. The math in Los Angeles is just the most visible example of the Growth Ponzi Scheme that’s playing out everywhere.

Across the country, local governments are discovering that growth doesn’t equal wealth. The numbers that looked like success — booming property values, record development, rising budgets — were all built on the same formula of deferred maintenance, unproductive infrastructure, and overextended debt. The illusion is fading, and what’s left is a landscape of obligations: liabilities that must be paid with revenue that never quite arrives.

The Strong Towns Finance Decoder shows this clearly. Whether it’s Los Angeles, Houston, or Atlanta, the pattern repeats: massive liabilities, thin reserves, and long-term obligations that dwarf available assets. We’ve mistaken motion for progress and volume for value. The result is fragility, a system that works when it’s new and then quietly stops working after the people who built it are gone.

Los Angeles is hitting the wall, but the same wall awaits every community that’s been trying to run faster than the math. The fix isn’t another round of growth; it’s a different operating system altogether, one that values productivity over expansion, resilience over speed, and stewardship over spectacle. That’s what a Strong Town looks like.

If you want to see where your own community stands, the Strong Towns Finance Decoder is free and open to everyone. Use it to explore your city’s financial health, see the numbers for yourself, and start asking better questions. Then, become a member of Strong Towns and plug into a movement that’s working to fix this problem, one block, one neighborhood, one place at a time.

.webp)