Last week, an elderly driver veered off West 133rd Street near High Drive in Leawood, Kansas, and struck a person walking on the sidewalk. The victim was hospitalized with injuries. The driver remained on scene.

An investigation is ongoing. Boxes will be checked. A police report will be filed. The community will mourn — it already is — and then, most likely, everyone will move on. But this wasn’t an isolated incident. It was a predictable outcome of systemic design failures that have turned one of the safest, most desirable suburbs in the Kansas City metro area into a case study in how North American street design kills people.

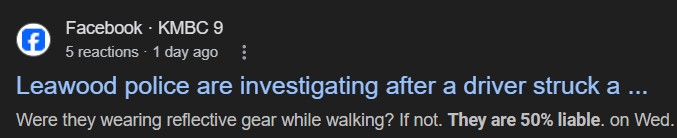

Just two days earlier, Taylor Havens, a mother of three, was struck at Lee Boulevard and West 85th Terrace. In October, 10-year-old Duke Ommert was killed while riding his e-scooter on Lee Boulevard near 103rd Street. He was wearing a helmet. At the conclusion of that investigation, police said, “As our community grieves this tragic loss, the Leawood Police Department reminds everyone — motorists, cyclists, scooter riders and pedestrians — to remain alert, stay aware of their surroundings, and look out for one another on our roadways.” The driver was found not at fault. Local parents, however, continue pressing for changes — anything: crosswalks, lights, wider sidewalks. They present different ideas, but they can all agree on one thing: this is not a safe place for kids.

That same month, 8-year-old Adam Duede was struck by a Ford F-150 after wobbling off the 83rd Street sidewalk. He survived. His mother called the family “incredibly lucky” it wasn’t worse.

At least 15 times in the past five years, someone walking or riding a scooter or bicycle in Leawood has been struck or endangered by a moving vehicle. The locations tell the story: 83rd Street, Lee Boulevard, 85th Terrace, 103rd Street, 133rd Street. This isn’t one bad corner. This is what happens when an entire community is built around streets designed to move cars quickly, with human life as an afterthought. Havens, the mother who was struck, thinks as much. "It's not if the next incident, it's just when," she told the local news.

The Reflexive Response: Who Messed Up?

After Duke Ommert's death, a neighboring city's council meeting revealed a familiar impulse. The focus: making riders more visible to drivers. One councilmember suggested helmets and e-scooters should have reflective stickers. A person in attendance stressed high visibility clothing as a must once the sun sets. It’s a common reflex following any crash after dark.

After nearly every pedestrian death, we ask: Who messed up? What could the victim have done differently? What imperfect behavior led to this tragedy?

This is the framework that governs how North America responds to traffic crashes. Emergency response personnel interview witnesses, draw schematics and check boxes. The primary purpose of these efforts is to assist in assigning blame. The investigation seeks to identify the responsible party — usually the driver, sometimes the pedestrian — so justice can be served and everyone can feel like the system worked. But here's what that framework systematically fails to ask: Why was this crash possible in the first place?

Consider what the parents know about Leawood:

“Kids are told no when they ask to bike to school, not because we don’t trust them but because we don’t trust the infrastructure,” said Abigail Fink, a Leawood mom, during a council meeting following Ommert’s death. “No child should have to navigate that risk just to get to school.”

She was one of dozens of neighbors pressing for the city to treat these corridors in what is otherwise one of “the safest neighborhoods in the city,” as an urgent safety risk. “We can’t undo the tragedies that have already happened. But we can prevent the future ones and we can give our children a childhood that happens outdoors,” added Lindsey Murray, another local parent and child psychologist. Adam Duede, the child who was struck but survived, was likewise present, advocating for something to be done on the corridor where he nearly lost his life.

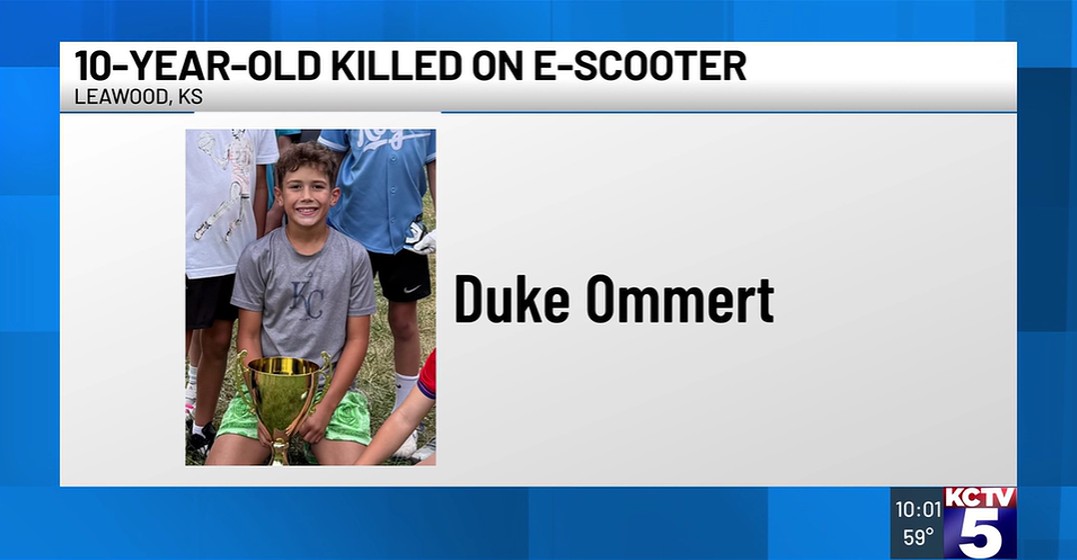

To the city’s credit, they’re open to change. In fact, plans were already in place to upgrade 83rd Street. The revised plan called for widening all 4-foot-wide sidewalks to at least 5 feet and 5-foot sidewalks into 6 feet. Though, city staff noted the road would need to be narrowed from the current 32 feet to 29 feet to make that happen. City staff likewise remarked that 29 feet is the minimum width recommended for cars to be able to pull over for emergency vehicles, which some parents found disappointing. There’s an irony, that the same wide roads needed for emergency vehicles are producing the very emergencies everyone is trying to avoid.

“It would be irresponsible for the city not to pause and take advantage of this opportunity to make necessary adjustments,” Kari Duede, Adam’s mother, noted. “I understand the budget concerns and I understand the city initiative to protect the trees, but protecting children and citizens has to be the priority.”

How the City Could Still Prevent the Next Tragedy

These parents have intuitively grasped what the Crash Analysis Studio methodology makes explicit: Crashes happen when there's a mismatch between what a street is designed for and how it's actually being used. And that it's better to act sooner, rather than later. Strong Towns developed the Crash Analysis Studio after witnessing cities repeat the same cycle: tragedy, blame, study, delay, and then tragedy again.

These children were not hit because Leawood drivers are uniquely reckless. They were hit because streets built to move cars quickly run straight through places where kids live, play, and travel. And sometimes those fast-moving vehicles collide with the people trying to exist there. Each crash is not just a tragedy — it is data. And they each present an opportunity to act.

The city’s proposed redesigns carry a price tag nearing $5 million, with safety improvements expected to push it higher. For street safety advocates, the fact that Kansas City officials are acknowledging that infrastructure plays a role is real progress. The fact that change is on the table is good news. But with 15 crashes in 5 years, Leawood cannot afford to keep waiting. The next step is to take a page from the Crash Analysis Studio handbook and ask: what can we do this week to make it safer. Even if it’s temporary. Even if it’s imperfect. Even if it’s not “the final design.”

Using the Tools at Hand

Parents and city officials alike have identified speed as a central problem. With that understanding, the immediate response should be simple: slow cars down in the places where harm keeps occurring. Cities do this all the time during construction. Barrels, cones, and temporary barriers go up overnight to protect workers and signal caution. The same approach can be used to protect children. It isn’t pretty. It isn’t permanent. But it can be deployed within hours after a crash to address the single biggest contributor to severe injury and death: speed.

The city can also use paint to visually narrow lanes near intersections and areas with frequent foot traffic. This sends a clear message to drivers to expect people in the street — and just as importantly, it restores dignity to those walking, who too often feel like intruders in spaces dominated by vehicles. The tools to improve safety already exist, and cost next to nothing.

No one wants a child to be killed by a car. Not the child. Not their parents. Not the driver. Not city staff, engineers, or elected officials. This is an outcome everyone agrees is unacceptable and yet it keeps happening.

We cannot solve this by assigning fault and hoping for better behavior. And we will not stop these recurring tragedies by pinning our faith solely on improvements promised months or years from now. It’s time we go beyond slow-moving, years-long redesign timelines and building a civic reflex that prioritizes immediate action over bureaucratic perfection. Lives are literally at stake.

For a deeper look at how cities can deliver safer outcomes sooner, Strong Towns produced the Beyond Blame report, which documents practical case studies and recommendations cities can use right now.

Places like Jersey City, NJ; Charlottesville, VA; and Indianapolis, IN are already putting these principles into practice, using Crash Analysis Studio insights to rethink dangerous corridors, respond more quickly after serious crashes, and implement low-cost, rapid interventions that slow traffic and protect people. Rather than waiting years for perfect redesigns, these cities are building systems that treat every serious crash as a signal to act immediately and reshape the street in real time. In corridors that once saw regular serious injuries, cities have introduced quick-build safety measures and seen reductions in severe crashes, fewer repeat incidents, and safer conditions for people walking, biking, and driving alike.

These are not theoretical improvements or distant promises. They are practical, measurable gains achieved by acting sooner, learning from each crash, and refusing to wait for perfect plans before protecting lives. Your city can follow that same path.

.webp)

[[divider]]

Responsible cities analyze traffic crashes to save lives. Yours can too.

Adopt the Crash Analysis Studio model and build a response focused on preventing future harm, not just assigning blame.

.webp)

.webp)