Across the country, school districts consistently make a calculated decision: they build new schools on the far edge of town, on land chosen not for its proximity to students or its connection to neighborhoods, but for its low sticker price and regulatory ease. These decisions almost always rely on one critical assumption: that someone else will pay to make the site accessible. That “someone else” is usually the state and federal governments.

When local officials plan for new schools, they often count on federal dollars to provide the roads, signals, and safety features needed to make isolated sites accessible. This expectation creates a feedback loop: choose the cheap land on the edge of town, and rely on outside money to make it work. Over time, this strategy has become standard practice, not because it's the best choice for students or communities, but because the funding systems generally rewards it. For students, this often means longer commutes, less independence, and fewer opportunities for physical activity and social interaction on the way to and from school. For families, it adds complexity and cost — having to coordinate drop-offs, navigate traffic, or trust in long bus routes that stretch already packed schedules.

Situating schools far from the communities they serve makes education less a part of daily neighborhood life and more of a destination managed by logistics. Students are treated less like small humans we are trying to nurture into maturity, and more like UPS packages to be routed and delivered on time.

A Hard Lesson in Small Town Arizona

The problems that shape daily life — sidewalk gaps, unsafe crossings, missing links between people and the places they want to be — are messy. Yet federal infrastructure programs are structured to look past them, chasing large, easily defined capital projects. They favor visibility over nuance, and one-time appropriations over long-term practicality.

The town of Pima, Arizona (population: 2,847) learned this lesson the hard way. When construction began on a new high school — only the second in the town’s 145-year history — it was placed on a 44-acre parcel next to a highway, with no practical way to get there. This new campus replaced a traditional neighborhood school, one where access was not an issue and students could reasonably walk or bike.

Rather than reinvest in a site already embedded within the community, the district chose a location that immediately introduced access challenges, requiring major infrastructure just to make the site usable. To address their accessibility problem, local officials sought and secured a $1 million federal grant to build the access road and traffic light that would make the school functional. Then, as part of a broader budget deal in Washington, the grant disappeared. The town was left with a school that students couldn’t safely reach, and no clear way to open it.

This story is not an aberration. It’s a clear example of how local leaders, working within a system shaped by external funding incentives, make strategic choices that prioritize short-term cost savings over long-term accessibility. In Pima, officials didn’t simply overlook the needs of students and families — they made a deliberate decision to place the new high school on remote land and count on federal infrastructure funding to make it viable.

That gamble didn’t pay off. But even if it had, the result would have still been a school that was harder to reach than the one it replaced. The failure here is not just in lost funding, but in building a public asset that depends on complex logistics and fragile support instead of serving the people right where they are.

Remote by Design, Dependent by Default

Time and again, communities choose to build schools on the cheapest available land, typically at the edge of town, far removed from where families actually live. This choice reduces upfront costs, but it pushes ongoing burdens onto everyone else: parents navigating daily traffic jams, school staff with extended commutes, and taxpayers at every level who end up funding the infrastructure needed to make these sites marginally functional.

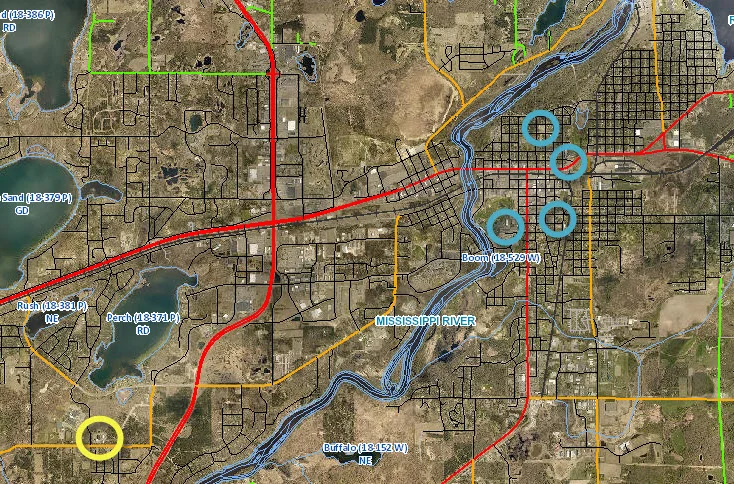

Forestview Middle School and Eagleview Elementary, two large campus-style schools in central Minnesota, are prime examples. Each occupies a remote site, selected not for proximity to students or neighborhoods, but for cost and construction convenience. No safe routes existed to these sites when they opened, and none were planned. As a result, students can’t safely walk or bike, and parents must contend with the vehicle congestion that this isolation creates.

To make these facilities usable, both districts relied on state and federal transportation dollars to build the necessary road infrastructure. And now, after-the-fact, both are pursuing Safe Routes to School grants to retrofit walkability into places where walking was never considered in the original design.

The logic is entirely backward: instead of building a school on a safe route, we build it in an inaccessible location and then look to higher levels of government to patch the problem later.

It Doesn't Have to be This Way

A more resilient system would start by recognizing a hard truth of the federal government's role in local transportation spending: much of today’s spending is being used to fix problems that previous rounds of spending helped create. We’re compensating.

The federal government has tried to compensate for these impacts by launching programs that delve into local complexities they’re poorly equipped to handle. Addressing nuanced issues like pedestrian safety, neighborhood accessibility, and coordination of land use patterns is destined to be ineffective when attempted from a top-down vantage point. It lacks the local knowledge, responsiveness, and flexibility required to do it well.

If we want walkable schools, we need to start building them where walking is possible. Programs like Safe Routes to School try to patch this gap, but they come too late, and actually enable the dysfunction they are trying to solve.

This approach is the direct result of having a large pool of federal transportation money without a focused federal function for how it should be used. In the absence of such a framework, the federal role has expanded beyond its appropriate scope, stretched to respond to every local problem, no matter how specific or nuanced. The result is a funding stream that not only struggles to address the problems in front of it, but crowds out the kind of innovation and reform that should be happening at the state and local level. Instead of empowering communities to make smart land use choices, it sustains systems that are dependent on inefficient infrastructure, costly logistics, and inflexible design. It prizes systems that prioritize technical compliance over contextual effectiveness.

The better investment is upstream: site selection. Neighborhood integration. A humble return to empowering local communities to think critically and design solutions that reflect their own context, values, and needs.