“How does a former shopping mall become a real neighborhood?” Indianapolis-based urban planner Jeffrey Tompkins asked on LinkedIn. “Incrementally.”

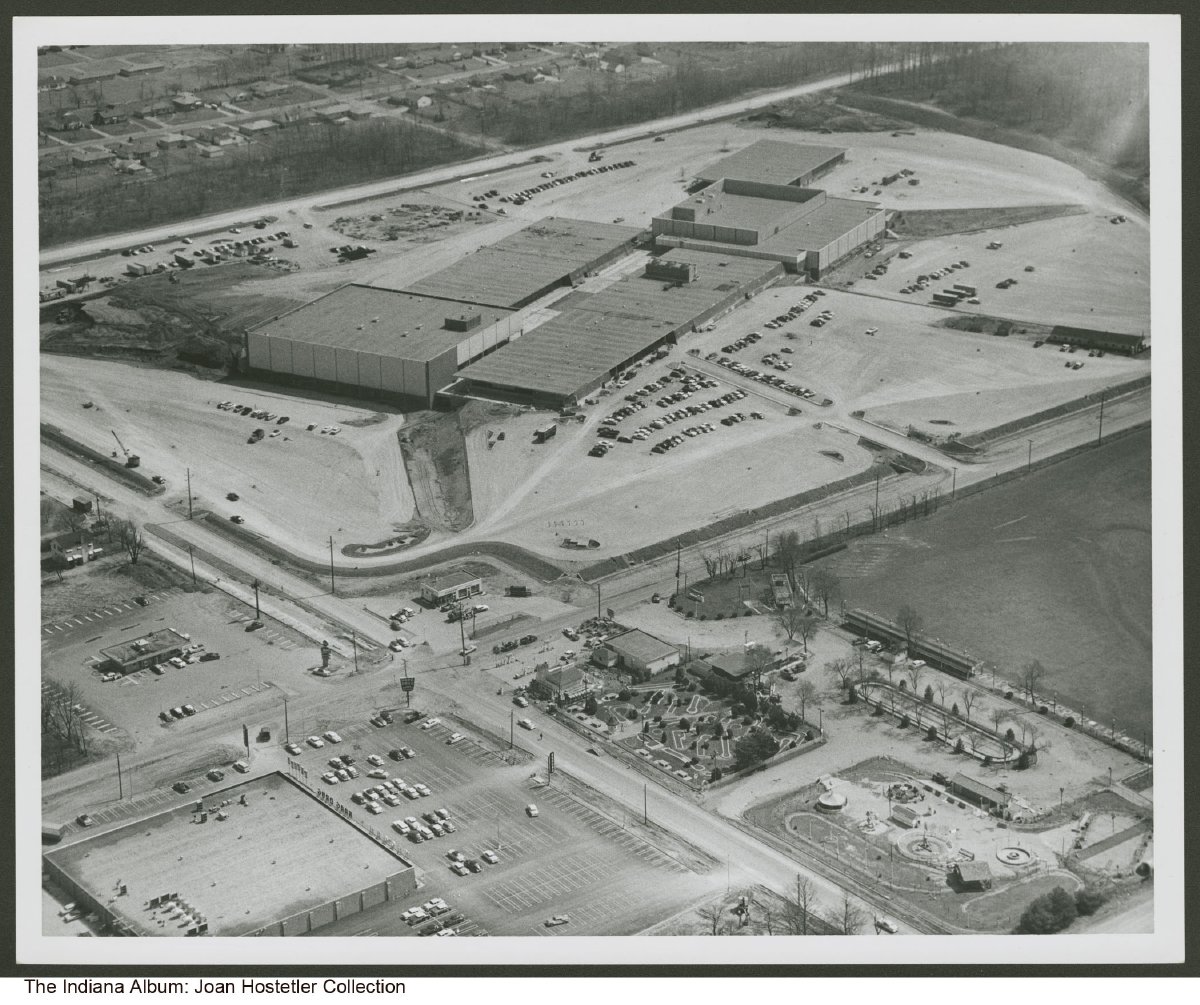

In 1955, The Indianapolis Star announced plans for what it called the nation’s — perhaps even the world’s — largest retail plaza: the Glendale Shopping Center. It broke ground a year later, and in 1958, the open-air complex welcomed its first customers. Shoppers strolled between two tunnel concourses that connected the wings of the mall.

But by the late 1960s, like so many of its peers, Glendale was enclosed — transformed into a climate-controlled retail fortress that thrived for a time, and then slowly faded as the “retail apocalypse” and newer mega-malls drew investment elsewhere, Tompkins noted.

By the late 1990s, this once-prized landmark in Indianapolis had entered what another observer called a “downward spiral.” Stores cycled in and out. Renovation plans sputtered. The hard truth became impossible to ignore: Glendale would never return to its mid-century heyday. So the question facing Kite Realty Group — the mall’s new owner — wasn’t how to revive a dying mall. It was: What comes next?

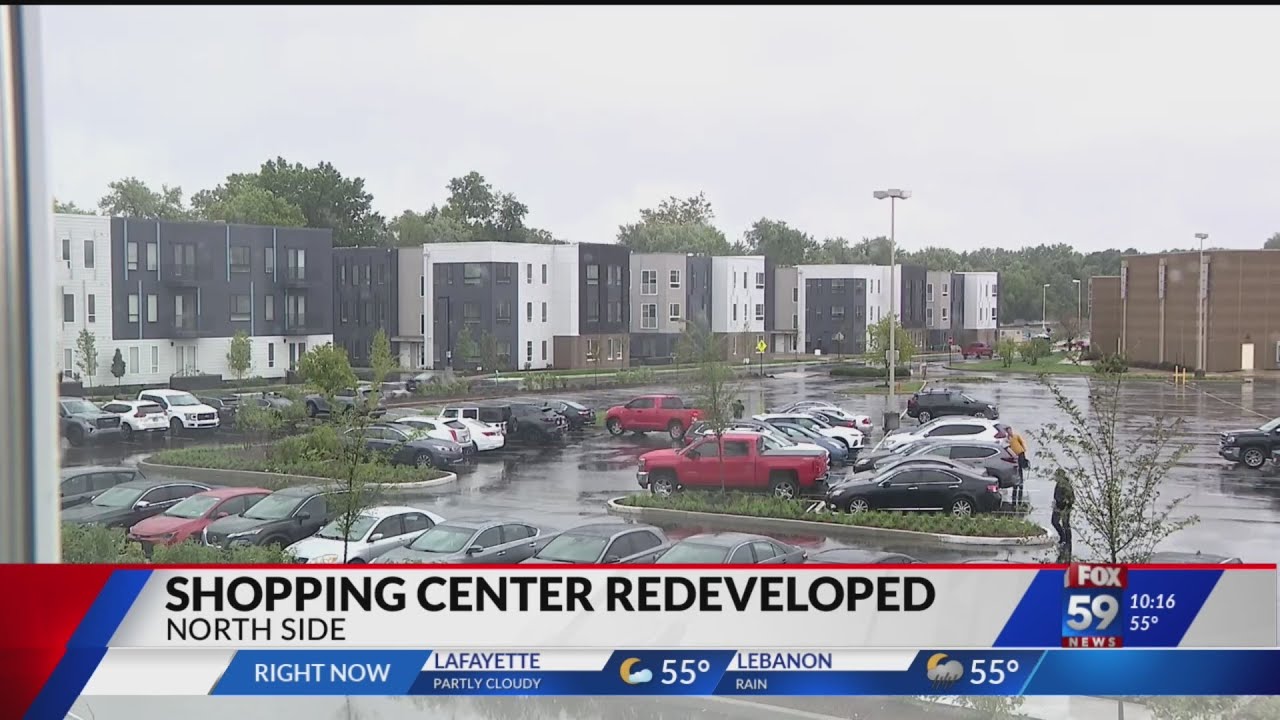

Instead of clinging to the idea of a single-use shopping destination, Kite opened the door to full-time community life. A pivotal early step was welcoming a branch of the Indianapolis Public Library in 2000, a signal that the site could serve as more than a Saturday errand. Over the next 25 years, the property reinvented itself in small, cumulative moves. Large retail boxes were subdivided. Local businesses moved in. Underperforming tenants moved out. Every few years, Glendale was re-evaluated and reshaped, not with one grand plan, but with a steady commitment to making the site useful, financially stable, and connected to everyday life.

Glendale’s transformation wasn’t seamless. Some tenants were upset when leases ended, and others felt they never had a fair chance to stay. The process had its missteps, and there are lessons here about communication and supporting small businesses through change. But even with its imperfections, the incremental approach allowed Glendale to evolve piece by piece rather than suffer the fate of so many dying malls. The process wasn’t perfect, but the direction was right.

In 2024, a new and expanded public library opened its doors. And just this week, zoning filings revealed the next phase: 190 additional apartments and, crucially, 48 for-sale townhomes. “This is the final puzzle piece,” Tompkins said. “By introducing homeownership alongside rentals, Glendale is graduating from a "commercial campus" to a permanent neighborhood.”

It’s not the mall it once was, but its “golden era” was never coming back. Today, the Glendale Town Center, as it is currently known, is something better: a place where people live, access daily needs, meet friends at the library, and contribute to a local tax base that isn’t sinking under a dying mall’s maintenance costs. It is, in every sense, a town center.

What Makes This Possible?

(And why is it still so hard?)

Much like aging office buildings downtown, dying malls are being eyed for housing, mixed-use development, and other forms of reinvention. But while the opportunity is great, the barriers are equally formidable. Technically, these structures weren’t designed for full-time residential life. They need new utilities, structural changes, and significant reconfiguration. Culturally and legally, the obstacles are bigger. Codes written in the post-war era often forbid exactly the kind of incremental innovation and reclamation that would give these places a second life.

Duncanville, Texas, where Monte Anderson — profiled by The New York Times for his “multigenerational roommate house” — is retrofitting a struggling suburban strip center offers an interesting case study. When I spoke to him, he was sitting in an office he built on-site. His daughters stop in often. His cat wandered through the frame during our call. In other words, a place long dismissed as an eyesore is already showing signs of life.

Anderson’s approach began with the most underutilized resource: the parking lot. If even a portion could be converted into modest apartments, residents would return, demand for nearby businesses would return, and the property could finally pay its own way instead of dragging down the city’s balance sheet. He can design the buildings, hire the contractors, and meet modern safety codes. But he can’t, by right, build them.

To add homes, he needs rezoning. He needs a parking variance. He likely needs conditional approvals, special exceptions, and a stack of paperwork that grows thicker every time he makes progress. Each delay raises his costs. Each approval adds months. Each requirement is an opportunity for the project to stall out.

Anderson is moving ahead, and he’s excited about it, but it should not require heroism to bring a dead commercial property back to life.

What a Housing-Ready City Would Do

A housing-ready city would take a hard look at the rules that have shaped the last half-century and ask whether they’re serving local goals or just perpetuating a culture of rote compliance. That means reevaluating:

- Arbitrary minimum lot sizes, which raise housing costs and shut out small businesses before they begin.

- Mandatory parking minimums, which consume land, inflate project budgets, and crowd out homes and local shops.

- Prohibitions on entry-level housing types, like starter homes, backyard cottages, small apartment buildings that were once normal parts of cities but are now illegal by default.

The modest, incremental buildings that once filled every town have become special exceptions requiring lawyers, fees, variances, and years of process. Retrofitting a mall is never simple. But we can make it simpler. Cities should be leading the way, not standing in the way.

If your city is ready to clear the path instead of adding to the maze, the Strong Towns Housing-Ready Toolkits offer case studies and ideas worth borrowing. The toolkits were shaped by hundreds of conversations with local officials, small-scale builders, and neighborhood advocates about the real obstacles they encounter and the steps that help unlock progress.

.webp)

.webp)