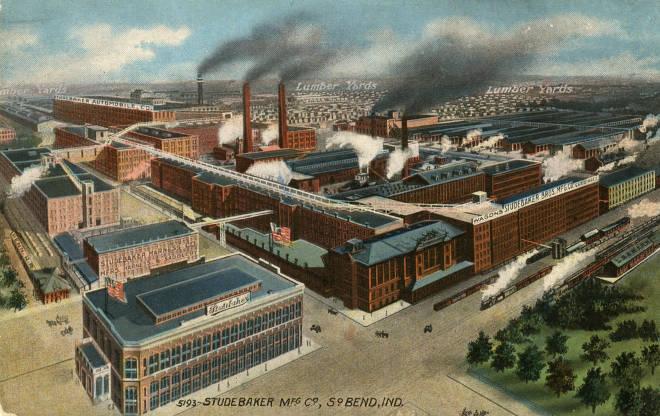

In the 1940s and ’50s, South Bend was the site of the American promise. Downtown bustled with department stores and lunch counters, neighborhood business districts hummed with local shops, and block after block of modest single-family homes filled with workers walking to and from shifts. Studebaker, the automotive manufacturer, anchored it all.

South Bend was a place where a good job at the plant could reliably support a household and send kids to college. At its peak, the company employed tens of thousands, drawing families from across the Midwest and sustaining a dense web of small businesses, civic clubs, churches, and social traditions. Families bought homes, settled into neighborhoods, and built lives around the idea that the factory’s future and their own were intertwined.

Then the bottom fell out.

By the mid-1960s, the Studebaker shutdown became the city’s defining story — so dominant that for half a century you couldn’t mention South Bend without someone sighing, “well, you know… when Studebaker left.” In 2011, that narrative was so entrenched that Newsweek listed South Bend among the “Dying Cities of America.” The label stung not because it was mean, but because it confirmed what many already believed: it was over.

Yet, if you spend time in South Bend today, you’ll rarely hear Studebaker come up at all. At least, that's what Mike Keen told me. Keen is a local. He’s also a former university professor-turned-incremental developer. Most importantly, he’s part of South Bend’s revival. It’s not that the wound has vanished, he explains. It’s still part of the city’s story, but it’s no longer the story of South Bend. It’s a part of history. Eventually, he hopes, it’ll be a footnote.

For decades, the city was frozen in a narrative that cast the past as destiny. Today, it behaves like a place that understands the past is the past and the present is where the future gets built.

The Next Best Time To Plant a Tree is Today

Keen’s work exemplifies this shift. After the 1,000 Homes in 1,000 Days initiative concluded, his neighborhood was pockmarked with empty lots. The program had been pitched as blight removal, targeting streets lined with dilapidated homes. Those homes were indeed eyesores — they attracted crime and reinforced the city’s low morale — but demolishing them left entire blocks hollowed out, with no immediate plans to rebuild on the newly vacated lots.

Instead of waiting for a master plan or a single catalytic investment, Keen began assembling homes and vacant parcels one by one. He helped launch the Portage Midtown Initiative and the South Bend GreenHouse, restored neglected homes, cultivated community gardens, and supported local builders learning to tackle small projects themselves. He often refers to these lots collectively as his “farm.”

Each small intervention stabilized the block, which encouraged additional investments, drew in new residents, and gradually restored confidence.

All the while, he was hosting gatherings at his own home to connect local developers, city officials, contractors, architects, and neighbors. He told me how those home gatherings grew from five to twelve to sixty to nearly a hundred people in a blink. The guiding philosophy was simple but radical: development is most effective when it is inclusive, collaborative, and rooted in a deep understanding of a specific place. And in order for that to work, everyone had to come sit at the table.

Many Hands, Many Bets

Keen wasn’t alone in this work. There were already dozens of residents committed to revitalizing their neighborhoods. What he helped do, is make them realize they’re all part of an ecosystem.

Barbara Turner of Revive Homes LLC leverages her own resources to restore homes in her community. Sarah Hill, a public library administrator, renovates historic houses through Penny Hill Homes. Consuella Hopkins launched Swella’s Ville, a mixed-use district with homes and office space designed to anchor economic revitalization on the west side. Jordan Richardson and Tony Ruiz are restoring their own neighborhoods, rebuilding homes, and creating opportunities for residents historically shut out of ownership. Each project strengthens the next, creating a network of care and action. And each of these developers shares a simple mantra: if I can do this, anyone can.

Keen’s initiative helped surface and connect these existing efforts, creating a collaborative ecosystem where knowledge, contractors, lenders, and technical expertise circulate openly. Keen calls this approach “finding your farm”: pick a manageable area, commit to it for the long haul, and engage deeply with neighbors and local stakeholders. This networked approach transforms development into something more akin to community organizing.

By working this way, developers can identify undervalued opportunities, build trust, and create a virtuous cycle where each project strengthens the next. As Keen told Strong Towns years ago, “I see the small-scale development approach as a form of DNA… If you have a dandelion seed, a bird can drop it anywhere, and it’s going to create dandelions. Unless something is really wrong with that place, something will grow.”

Today, what sets South Bend apart from its Studebaker-era past is the distribution of investment and effort. One factory once anchored the city, so its failure brought everything else down with it. Today, the city’s revival is built on many hands, many bets.

The city itself has become a facilitator. Champions like Tim Corcoran, the city’s Director of Planning, revisited the policies and codes that were holding the city back. Eventually, the creation of the Department of Economic Empowerment created a pathway for technical support and connected small developers to contractors, lawyers, and lenders. Workshops like Build South Bend teach the nuts and bolts of small-scale development, giving residents the tools they need to stabilize and activate their own blocks.

South Bend’s revival is not a miracle. It’s the result of ordinary people taking ownership of their city, learning from failure, sharing knowledge, and acting where the system has failed to act. And in that, it provides hope — and a model — for cities across the country.

Step inside South Bend’s revival in the latest episode of Stacked Against Us. And explore the Housing-Ready City Toolkits to see how your community can grow stronger, block by block.

.webp)