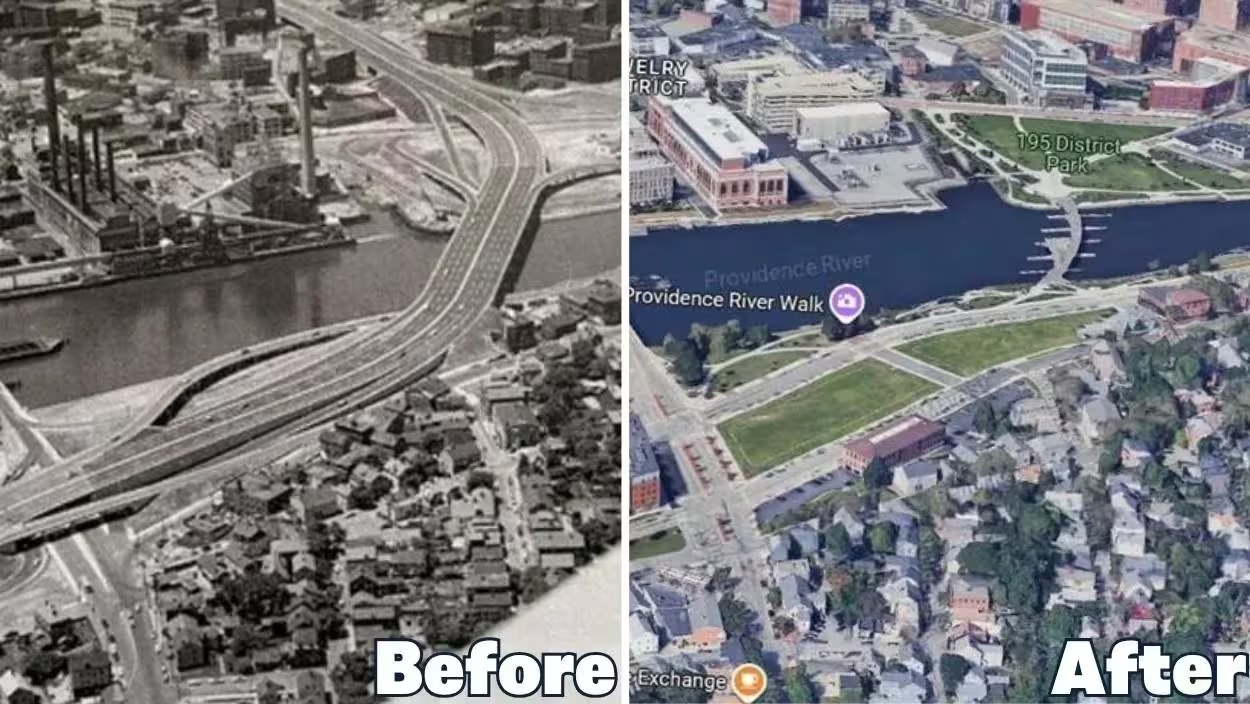

Removing an urban highway is a major accomplishment. It’s a win for local residents, small businesses, and anyone who wants their city to be more connected, beautiful, and walkable. But the work doesn’t end when the last ramp comes down.

Urban highways leave scars. They reshape streets, carve through neighborhoods, and stifle the kind of street life that makes a place thrive. The good news? Humbly observing these scars and the effect they have on the community can help you identify the next smallest step to healing.

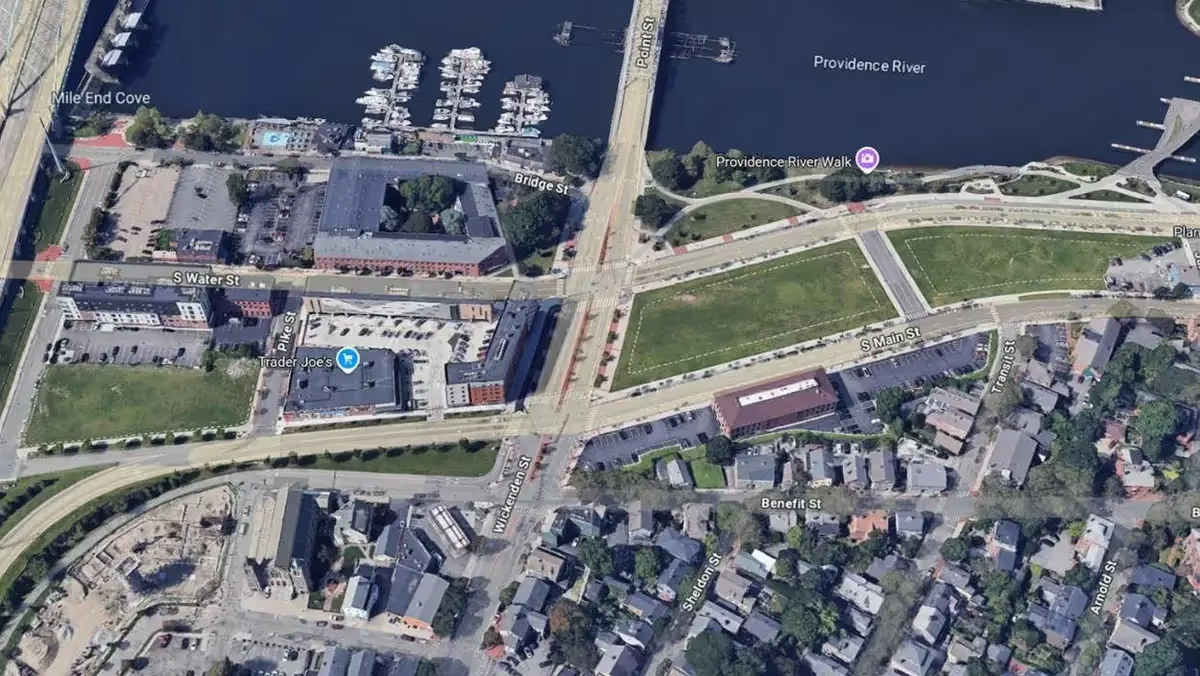

The Rhode Island Department of Transportation removed a portion of I‑195 from Providence’s urban core in 2011. Last month, I attended a walking tour in the area led by Dylan Giles of Providence Streets Coalition, Peter Erhartic of Building Block Community Development, and Kip Santos of Strong Towns Providence. Here are some of the lingering effects the highway had on the community and how Providence is addressing them.

Empty Space That Divides the Community

The most obvious scar left by the highway is the swath of empty land cutting through the heart of the neighborhood. While this green space is an improvement over the highway, it still divides the community and makes the area less walkable. With a lively waterfront park just across the street, there’s no benefit to keeping this land undeveloped.

Fortunately, the commission in charge of redeveloping the highway seems to understand that too. They’ve already started filling in the two blocks on the south side of Point Street (the left side in the image). One of these new additions is a five-story mixed-use building, which has housing on upper floors and local businesses on the ground floor. This addition greatly improved the walkability and appeal of the area, our guides said. The development commission plans to repeat this success by adding mixed-use buildings on the remaining empty plots. This will extend the commercial core of the community and firmly reconnect the two sides of the neighborhood.

Streets That Act Like Highway Ramps

Another remnant of I-195 is the design of Main Street and South Water Street. These streets used to be highway on- or off-ramps, and they’re both one-way streets with two wide lanes of traffic. This design may have been appropriate for highway ramps, but now it encourages speeding on neighborhood streets. It also puts people on foot in double jeopardy: Even if a driver in the nearest lane stops to let a person cross the street, a driver in the far lane may not notice the pedestrian.

This design problem was especially obvious on South Water Street. While Main Street is surrounded by close-set buildings for much of its length—a remnant of the city’s pre-highway design—South Water Street was bordered by the river and mostly empty land. That made it an ideal place for drag racing, our guides told us. Providence addressed this problem by reconfiguring the street in 2021. The city turned one of the lanes into a multimodal path and added pedestrian refuges. This new design made it very difficult to break the law, and crashes dropped to almost zero.

(Unfortunately, Providence’s new mayor has decided to turn South Water Street back into a two-lane street. Local advocates are working to ensure the design remains as safe as possible. Even if it ends up being temporary, the reconfiguration of South Water Street remains a good example of addressing dangerous street design in a smart and inexpensive way.)

Minor design changes were also made on Main Street, including curb bump-outs at intersections. These changes, combined with the optical narrowing of close-set buildings, tell drivers to slow down. It doesn’t address the double jeopardy problem for pedestrians, though, so local advocates are still campaigning for a more substantial reconfiguration.

Buildings That Turn Their Backs on the Street

A more subtle consequence of urban highways can be found in the buildings around the former highway. One example is the condos on one side of Main Street. These condos were built during the “urban renewal” that brought the highway into Providence. They open onto a rear parking lot, leaving several blocks of blank wall along the street. The impact is clearly visible, our guides explained. They rarely see people walking on the condo’s side of the street. The other side, which is lined with mixed-use buildings full of local shops, is almost constantly occupied.

Our guides described this as a problem of porosity. When buildings don’t have easily accessible entrances, it tells people that they’re not welcome in the area.

South Water Street also faces porosity challenges. While there are buildings lining a portion of the street, only two of them actually open onto it. The others are closed off from the street or only have entrances to parking lots or garages. This deadens one of the neighborhood’s greatest assets: the riverfront. Where there could be a lively edge of shops, cafes, and gathering spaces, there’s instead blank walls and asphalt.

Fortunately, Providence has the opportunity to bring South Water Street back to life. Large parcels of land along the street are up for redevelopment into mixed-use buildings. If those buildings are designed to open onto the street, it would inject more porosity—and thus more appeal—into the area.

The Main Street condos would be more challenging to address, our guides said, since ownership is shared among many people. It would likely be easier to push for a redesign once the condos get old enough to need replacing. Until then, local advocates and officials are focused on other ways to improve the corridor, such as narrowing the street to one lane.

.webp)