For more than a decade, I’ve been arguing that America’s housing problems aren’t just about how much we build, or where, or how fast. They’re about the system we’ve built around housing. That system treats rising prices as success, falling prices as failure, and political intervention as the only acceptable response when the math stops working. I wrote a book about this two years ago because the pattern had already been clear, even if it wasn’t widely acknowledged.

What’s changing now isn’t the underlying reality, but the range of places where that reality is becoming visible. Arguments that once lived on the margins — about price protection, financial risk, and the limits of supply-driven solutions — are now showing up in institutions and conversations that rarely question the dominant narrative. National leaders are saying the quiet part out loud. Academics are openly disputing assumptions that were treated as settled. Even the data from our most technocratic institutions is pointing in the same direction.

That doesn’t mean the housing debate is resolved. Far from it. But it does mean we’re being forced to reckon with a basic truth I’ve been trying to surface for years: we don’t live in a housing system designed to deliver affordability through falling prices.

Consider a moment from late January, when the president stated plainly that he does not want housing prices to go down. He wants them to go up, specifically to protect people who already own homes. The suggestion wasn’t subtle. Lower interest rates would make homes easier to buy, he said, but prices should remain high so existing owners stay “wealthy.”

To some housing advocates, this sounded unhinged. On social media, the reaction was disbelief, even outrage. How could a president openly oppose lower housing prices in the middle of an affordability crisis?

The answer is simpler — and more uncomfortable — than many want to admit: this has been the foundational housing policy of the United States since the end of World War II. Every major political party. Every serious national politician. Every administration. All of them treat rising home values as a public good and falling prices as systemic risk. When affordability breaks, the response is not to allow prices to correct downward, but to expand credit, subsidize demand, or intervene politically to stabilize values.

What made that recent moment with President Trump jarring wasn’t the policy. It was the honesty.

If that shocks you, it’s likely because you’ve been operating with a different mental model, one where housing affordability is primarily a technical problem. Loosen the right rules, allow enough construction, and prices will fall. When they don’t, the explanation is straightforward: we didn’t go far enough, fast enough, or with enough political will.

It’s an appealing story. It offers moral clarity and a direct line from problem to solution. And in some places, under some conditions, parts of it are even true. But it also assumes we’re operating in a political and financial environment that tolerates price declines, absorbs losses quietly, and allows markets to run their course.

That assumption isn’t true, particularly at the national level, a reality now being acknowledged more openly.

A recent article in the Washington Post surveyed a growing body of academic research challenging the link between new housing supply and broad affordability. Even under optimistic assumptions, the math is sobering. In high-cost cities, even aggressive new construction would take decades to bring rents down to levels affordable to working-class households. In some scenarios, more than a century. And that’s assuming sustained construction rates that few places have ever achieved without triggering political backlash or financial pullback.

What’s striking isn’t that some scholars disagree with the sweeping narrative of nationwide undersupply, but that this skepticism is now being treated as legitimate rather than heretical. The confidence that increasing supply alone will reliably deliver affordability, on timelines that matter to real people, is weaker than public rhetoric suggests.

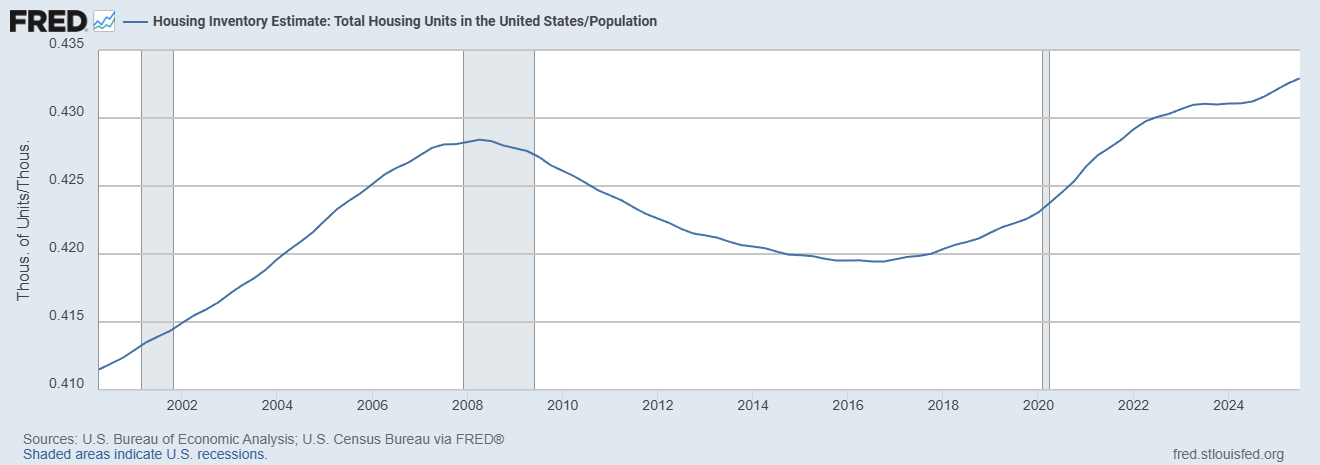

Then there’s the data that rarely makes it into these debates. According to the Federal Reserve’s own figures, housing units per capita in the United States have been rising steadily since the mid-2010s and now exceed pre-Great Recession levels. That doesn’t mean every community has enough housing. Housing markets are local, segmented, and deeply shaped by place. But it does complicate the claim that we are facing a uniform, national shortage that can be solved with a single, national prescription.

Put these pieces together — the politics, the scholarship, the data — and an undeniable picture emerges. Prices are rising not simply because we aren’t building enough, but because we’ve embedded housing in a national financial system that depends on price appreciation to function. Capital flows freely into housing when prices are rising, pulls back quickly when they flatten, and exposes local governments, builders, and households when the cycle turns. The system protects incumbents by design and treats widespread price declines not as a correction, but as a threat.

The variable most housing debates gloss over is who is expected to absorb loss when things stop going up, as well as how aggressively the system moves to prevent that from ever happening.

Financing pulls back long before prices crash. Builders stop building as margins thin. Local governments panic as assessments flatten. Pension funds, banks, and homeowners all push back against losses because those losses are real, concentrated, and politically salient. When the people and institutions bearing the downside are the same ones with the most influence, the response isn’t gradual adjustment to affordability. It’s to freeze existing asset values and financial arrangements in place and escalate intervention to prevent losses from spreading.

This is the context housing advocates eventually collide with. When local reformers push up against a system designed to protect asset values — and that system refuses to give — the natural instinct is to apply more force. When deregulation and new construction don’t deliver affordability quickly enough, the answer isn’t to slow down and reconsider the model. It’s to reach for more authority. State preemption. Federal mandates. Larger subsidies. Broader enforcement. More power, applied from farther away, with less tolerance for places that don’t perform as expected.

Escalation feels like the only remaining option when outcomes don’t match expectations. This isn’t a moral failing. It’s a warning sign that the theory of change is colliding with realities it wasn’t built to handle: financial constraints, political limits, and local complexity that can’t simply be wished away or overridden.

In political environments where success is measured by the ability to aggregate power and compel action, questioning that underlying theory can be surprisingly difficult. Doing so doesn’t just slow momentum; it calls into question whether the preferred tools — and the people best positioned to use them — are actually suited to the problem at hand. When that happens, it’s often easier to double down on force than to reconsider the model itself.

But when a theory of change requires ever-greater pressure to overcome financial realities, political resistance, and the limits of local capacity, it’s worth asking whether the theory is incomplete, not whether we’ve been insufficiently aggressive.

Strong Towns has always started from a different premise. Durable affordability doesn’t come from crashing markets or imposing uniform outcomes. It comes from places that can respond to stress without breaking; from systems that can adjust incrementally without needing to override the people who live there. And it comes from building up more communities that can offer real opportunity and prosperity, so demand naturally spreads across many places, instead of being forced into a handful of superstar metros that buckle under the pressure.

That work looks different than the fixes contained in our dominant narratives. It’s incremental. It’s uneven. It resists simple slogans and tidy political fixes. It doesn’t promise a single national solution, and it doesn’t pretend we can wish away the political economy we’re operating inside.

But the Strong Towns approach has one crucial advantage: it begins in the world we are actually in, not a theoretical one where the story gets too tidy, the villains too easy to identify, and the solutions too simple. As the pressures mount and escalation becomes the default response, realism is no longer a liability.

It is the only way forward that remains legitimate under pressure.

.webp)

.webp)