The invention of the printing press democratized access to information. With that came a lot of uncertainty.

Walking to school shouldn't be a death-defying stunt. That's why advocates in Maine are working with city leaders to make their streets safer.

At Ride for Your Life, hundreds rode to the Lincoln Memorial to mourn lives cut short by dangerous streets and to call for a future where no family has to endure the same loss.

Across the country, it’s clear that what truly makes a city resilient isn’t the plans, grants, or programs—it’s the people who care for one another and invest in their communities.

When homes are priced beyond what local incomes can sustain, the system stretches the debt instead of fixing the root problem.

Strong Towns is more than ideas. It’s a movement powered by members taking real action in their communities.

In 2008, Strong Towns was just a small blog with a big question; by 2025, it has become a nationwide movement with hundreds of local groups making real change on the ground. Things have changed in countless ways, yet the core mission has never been clearer.

This project in Salem, Oregon, shows how federal funding rewards cities for optimistic benefit-cost narratives, not fiscal health or return on investment analysis.

After facing constant roadblocks in opening a neighborhood cafe, an artist in Savannah, Georgia, created a board game that mimics the frustration of small-scale development. It was a wake-up call for local officials.

How two identical park buildings reveal the power of small design choices.

Thanks to persistent local advocacy and city leadership willing to listen, change is finally coming to a dangerous intersection in New Haven, Connecticut.

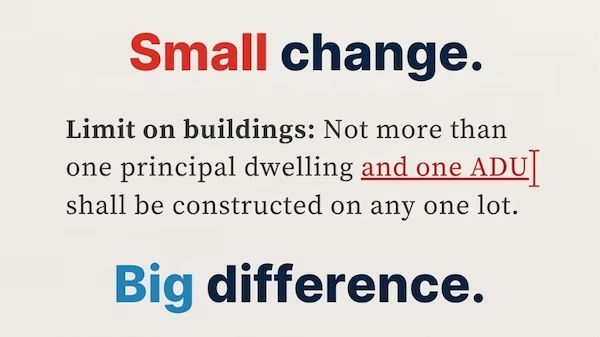

Small, precise zoning code text revisions can be a game-changer for communities facing housing shortages.

13 years after a new stadium and set of highway ramps promised to bring economic revitalization to Chester, Pennsylvania, things have only gotten worse.

With limited budgets and staff time, cities often reserve their safety interventions for the most dangerous locations. But that doesn't mean other areas are safe.

Better communication isn’t complicated. If your city wants more incremental development, start there.

Los Angeles didn’t mismanage its way into crisis. It built its way here.

The notorious Park Avenue in Minneapolis is finally getting some immediate safety improvements, thanks to the efforts of local advocates and county officials willing to step up.

For many small developers, the hardest step isn’t swinging a hammer or drawing a site plan; it’s figuring out where to start. Here's how Bentonville, Arkansas, is fixing that.

In Shreveport, Louisiana, a deeply controversial project aims to build a new highway directly through the city’s core.

In the heart of the Rust Belt, a city once defined by industrial decline is quietly rebuilding from the ground up.

Here's how Lafayette, Louisiana, became a national leader in supporting incremental developers and creating an ecosystem where community reinvestment thrives.

Volunteers in Spokane, Washington, sent a message to city hall last month by building, decorating, and installing 29 bus benches throughout the city.

If you want more affordable, resilient, and context-sensitive housing, you need to equip your residents to build it. Here's how Sacramento did it.

This group went from a struggling handful of advocates to a powerhouse for local change. Here's how they did it.