Editor’s Note: An addendum was added to Part One of this piece on April 28, 2021 to account for Water Resources’ user fees. The first paragraph of this piece, Part Two, was subsequently updated to include the new totals.

In the first half of this piece, we looked at the 5 simple steps to finding your city’s private to public investment ratio. We learned that Calgary has a private to public investment ratio of 3.6:1. (The Strong Towns recommendation is 20:1 to 40:1.) To replace its $84.7 billion of infrastructure, we found the City of Calgary should be collecting $3.41 billion each year or, because Water user fees should cover Calgary’s water infrastructure costs, $2.98 billion each year. To get that, the City would need to more than double its residential taxes.

How has Calgary kept this going so long?

I love Calgary, but it’s probably not the home of the Strong Towns Strength Test and I'm not nominating it for this year’s Strong Towns contest. Some parts of Calgary are probably highly productive in terms of value per area. Others are not. There’s more to life than productivity but a city needs to be productive enough that its revenue matches its expenses.

Calgarians, forgetting cities are complex systems, have focused on efficiency over resilience and removed feedback by separating and spreading out our land uses. The center of town is dense and has Calgary’s highest sources of revenue per area. This is likely the most productive part of the city in terms of value/area. Concentrating many jobs in one place can make it easy for people to change jobs without disrupting the rest of their lives. It can also continuously disrupt their lives with long commutes, and expensive housing and transportation.

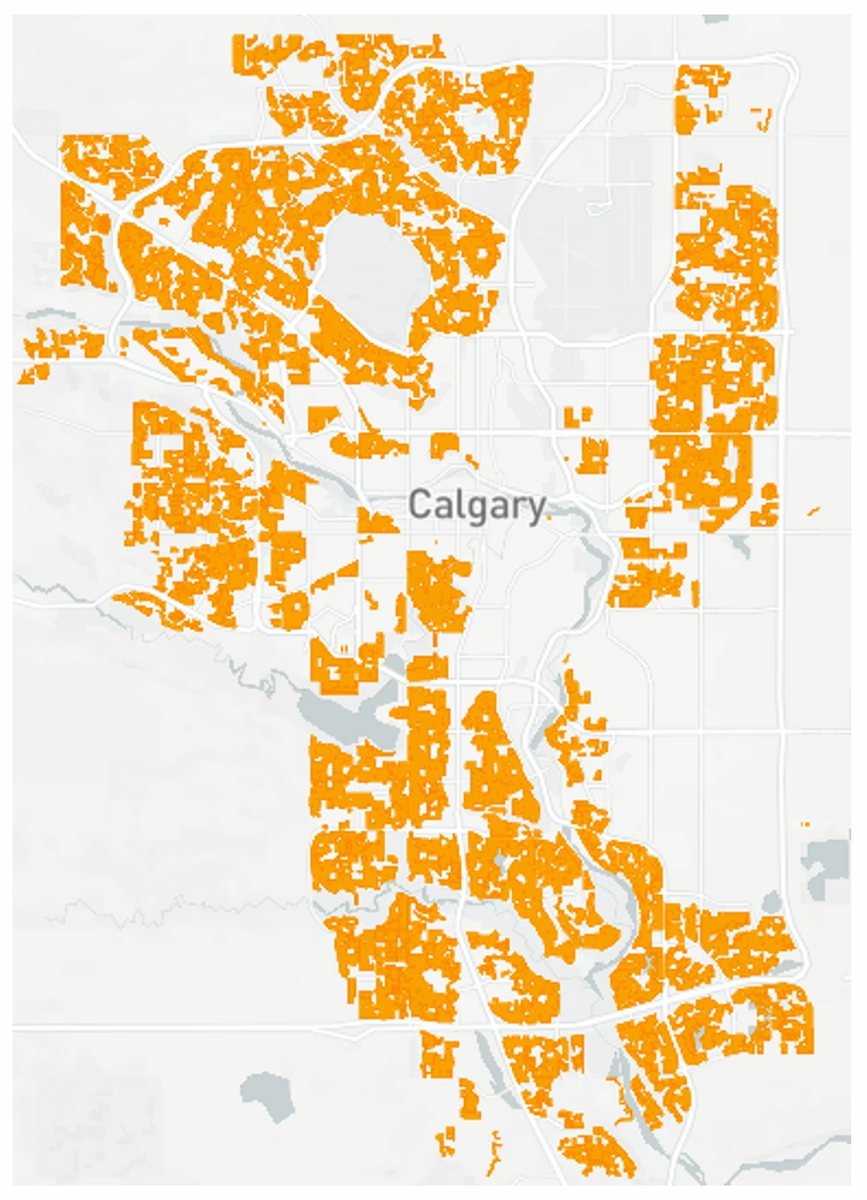

Like many North American cities, Calgary expanded after World War II and has relied primarily on perimeter growth since. Local debates about whether new neighborhoods pay for themselves or ”aren’t your grandma’s suburbs” ignore the areas between the core and periphery where detached houses tend to be the only permitted use, weren’t designed to be productive enough to pay for their own infrastructure, and are becoming a doughnut of declining population.

People may say they want low density and expensive infrastructure, but they can’t make fully informed choices because cities don’t consider long-term infrastructure costs. Continuing Charles Marohn’s lobster and hamburger analogy, it’s like eating at a restaurant where both lobster and hamburgers cost the same because the full bill doesn’t arrive until after the diners have left the table. Our cities are like an intergenerational dine-and-dash; someone’s children will get the bill.

Calgary: a fragile city

Calgary is fragile. Its success at hosting many head offices (peaking at 222 head offices in 2012) and profitable oil and gas companies buoyed up less productive parts of town. Businesses had higher property tax rates than residences. This is like taking a loss on 80% of what the City does while trying to make up for the loss with the last 20%. Businesses can try use Black Friday and holiday sales to make their annual profit in the last two months of a year, but cities are playing an infinite game; they cannot go out of business and sell their streets and pipes to neighboring towns.

Since 2014, oil prices have fallen and downtown offices have emptied. By fall 2020, 29.5% of downtown offices were vacant. Falling downtown property values lowered their owners’ property taxes. Though the City collected $250 million less in downtown property taxes from 2015 to 2018, municipal costs remained roughly the same. So City Council increased taxes for businesses outside of the downtown core, in some cases three to four times, until business owners complained. (Note: This is an excellent one-page explanation of Calgary’s property tax problem.) In the fall of 2019, Council voted to shift tax responsibility from 49% residents and 51% businesses, to 52% residents and 48% businesses. The City has offered tax relief for businesses outside of downtown. People are looking into adaptive reuse of downtown’s vacant offices. Yet, Calgary remains fragile if most parts of the city cannot pay to maintain their infrastructure.

How can Calgary become more productive?

Like most cities, Calgary can become more productive by prioritizing our infrastructure maintenance in places with the highest value/area and then in places most likely to become more productive. We can use public investment to quickly address people’s daily struggles. And we can allow at least duplexes and neighborhood-scaled businesses in every neighborhood so many people can incrementally invest where they live.

Calgary hasn’t excelled at allowing incremental growth. Until 2018, when City Council made secondary suites discretionary uses, people needed a public hearing before Council to change land uses so someone could live in their basement or backyard. These hearings took around 20% of Council’s meeting time. Between March and October 2020, 99% of applications were approved, which suggests suites could be allowed as-of-right.

“For local governments that complain that the finished housing is too expensive, the single thing that they could do that would be most useful is make the development process shorter, more streamlined and more transparent.”

— Jenny Schuetz on the Strong Towns Podcast (10:30)

Calgarians have another chance to become more productive. The City has proposed The Guidebook for Great Communities as a tool to create local area plans, consolidate design guidelines, and act as vision for a new land use bylaw. It’s not the simplest or fastest way to create a new land use bylaw, but it has potential. If we get it right, it could allow incremental growth everywhere and give residents a chance to decide where bigger buildings should go through local area plans. It talks about a variety of housing types up to three stories tall, which I hope means allowing missing middle housing everywhere. We don’t need to blame neighborhoods that aren’t productive enough to maintain their infrastructure, but we should be careful that people who claim that allowing the next increment undermines their neighborhood’s character don’t bankrupt our city.

City Council’s planning and urban development committee seemed receptive to this math when I shared it at their meetings about the Guidebook in January and February. Afterwards, I learned the City had talked about hiring Urban3 to do their excellent work in Calgary and having them present to the regional board. Other Calgarians supported those ideas and said they want the City to do more accurate math than this back of envelope math. We’ll see if the math helps persuade Council members when they vote on the Guidebook in March.

Southern Alberta is famous for chinook winds that can raise temperatures by 20 to 30 degrees Celsius (35 to 55 degrees Fahrenheit) in a few hours. Calgarians joke, “If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes.” We can’t predict next week’s weather, next month’s oil prices or next year’s Flames’ season. Yet, our zoning and infrastructure require a future that is as wealthy or wealthier than our past and present. Doing the math shows that we need zoning and infrastructure that will allow people to adapt in uncertain times.

Cover photo by Dorothy Mombrun from Pexels

.webp)