This is part of a short series exploring the “buttonhook” interchange at the intersection of Highways 371 and 210 in Baxter, Minnesota. Catch up with these columns:

- “Six Roundabouts to Nowhere”

- “The Buttonhook Isn’t Designed To Solve Baxter’s Mythical Congestion”

- "The Buttonhook and the Cost of Safety We Refuse to Pay"

In my last column, I asked how many people we are willing to kill so someone can get to Fleet Farm eight seconds quicker. The answer should be zero. But it never has been. And it isn’t now.

That’s because MnDOT’s buttonhook interchange project was never really about safety. It was never really about congestion, either. Those are the sales pitches. The real justification for the buttonhook, as local Chamber of Commerce president Matt Kilian put it, is “commerce.”

Commerce. That’s it. Let’s stop pretending otherwise.

The buttonhook project is being funded by the Corridors of Commerce program, a special pool of money the state created in 2013 to “foster economic growth.” That was in the early days of Strong Towns, when the ridiculous math of highway spending was largely unchallenged. Twelve years and nearly $2 billion of program spending later, we should know better. Readers of Strong Towns — a growing percentage of industry professionals, including many people working on this project — certainly do.

MnDOT describes Corridors of Commerce as a way to remove barriers to commerce, ease freight movement, and expand capacity. That’s what the state calls “economic development.” Not resilient local businesses. Not entrepreneurship. Not neighborhoods where wealth circulates and grows over time. Instead: faster trucks, highway access for chain stores, and more square footage of disposable development.

It’s hard to imagine a less sophisticated way to think about economic growth. It’s one step beyond Depression-era make-work programs where the government paid people to dig a ditch and fill it back in. At least the ditch didn’t come with miles of frontage roads, underground pipes, and the endless maintenance bills this kind of development creates for cities and their taxpayers.

At the heart of Corridors of Commerce is the backwards logic that makes the buttonhook project possible: If the strip looks busy and cars keep funneling into the big boxes, it counts as “commerce.” That’s the state’s version of economic development. It’s way too simplistic; we all need to move on from it.

Return on Investment?

Minnesota is a property tax state, which means if we’re going to talk seriously about “return on investment” — the very first scoring criterion in the Corridors of Commerce program — we need to talk about property value.

So, I went to the county’s GIS system, which is publicly available to anyone, and pulled the land values for the two corridors we’re talking about. It’s not complicated. Anyone working on this project could have done the same thing. And they would if they actually cared about return on investment and wanted to understand what’s really going on.

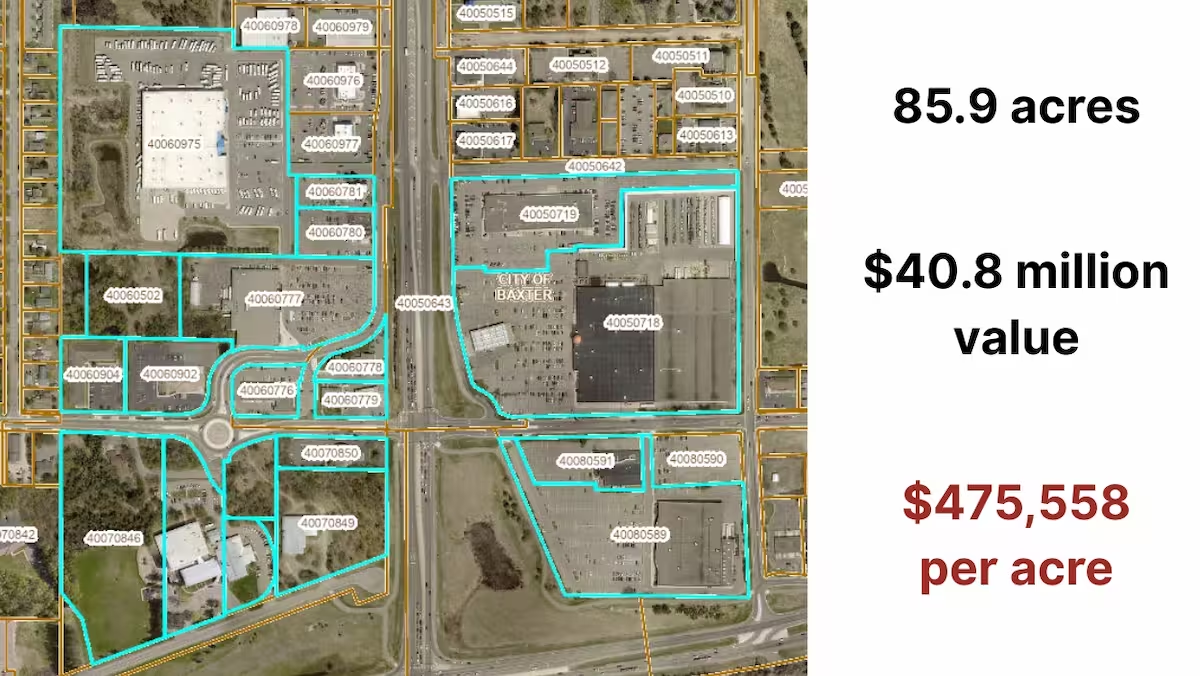

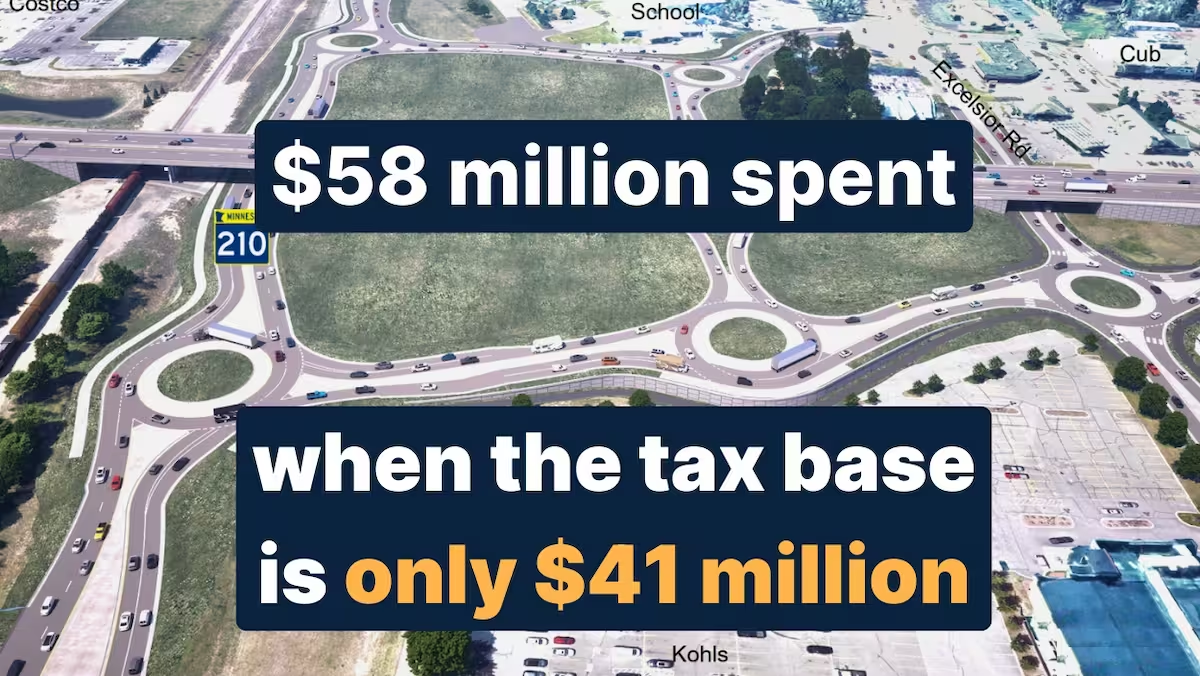

The first area is in Baxter, directly served by the proposed buttonhook interchange. MnDOT plans to spend $58 million to elevate Highway 371 over 210 and the railroad tracks, wrap the area in roundabouts, and preserve access to the strip of big-box stores and chains that cluster there. I analyzed the properties directly served by the buttonhook roundabouts, the ones we are spending tens of millions on providing direct access to.

The buttonhook area in Baxter contains 85.9 acres of land, with a total property value of $40.8 million.

Let’s pause here and note the obvious: MnDOT plans to spend $58 million on the buttonhook, which is more than the property it serves is even worth. By the city’s land use codes, these are properties that are already maxed out; there is no redevelopment or intensification plan in the works.

The state of Minnesota, through the Corridors of Commerce program, is spending $58 million to prop up $40.8 million of gas stations, strip malls, and big-box stores. Yeah, that’s messed up.

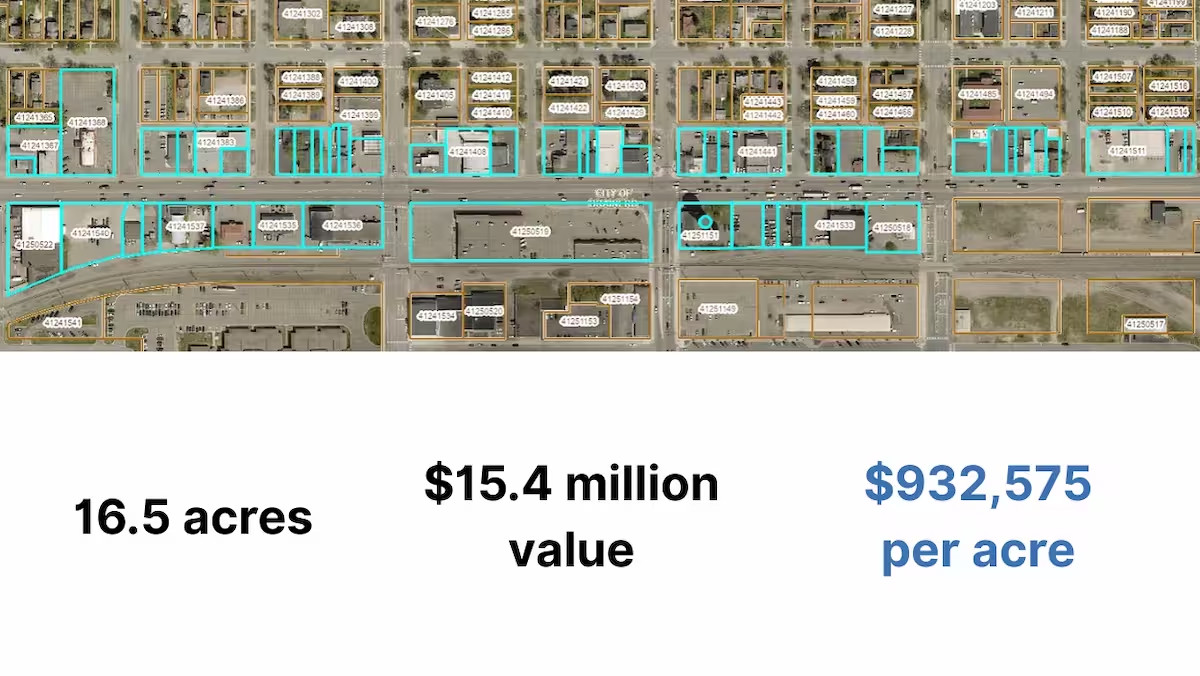

Here is the neighboring city of Brainerd and the Washington Street corridor that MnDOT is preparing to reconstruct at roughly the same time. Here, the plan is the opposite: close intersections, remove on-street parking, and move traffic through the city more quickly, even though this is part of Brainerd’s core business district.

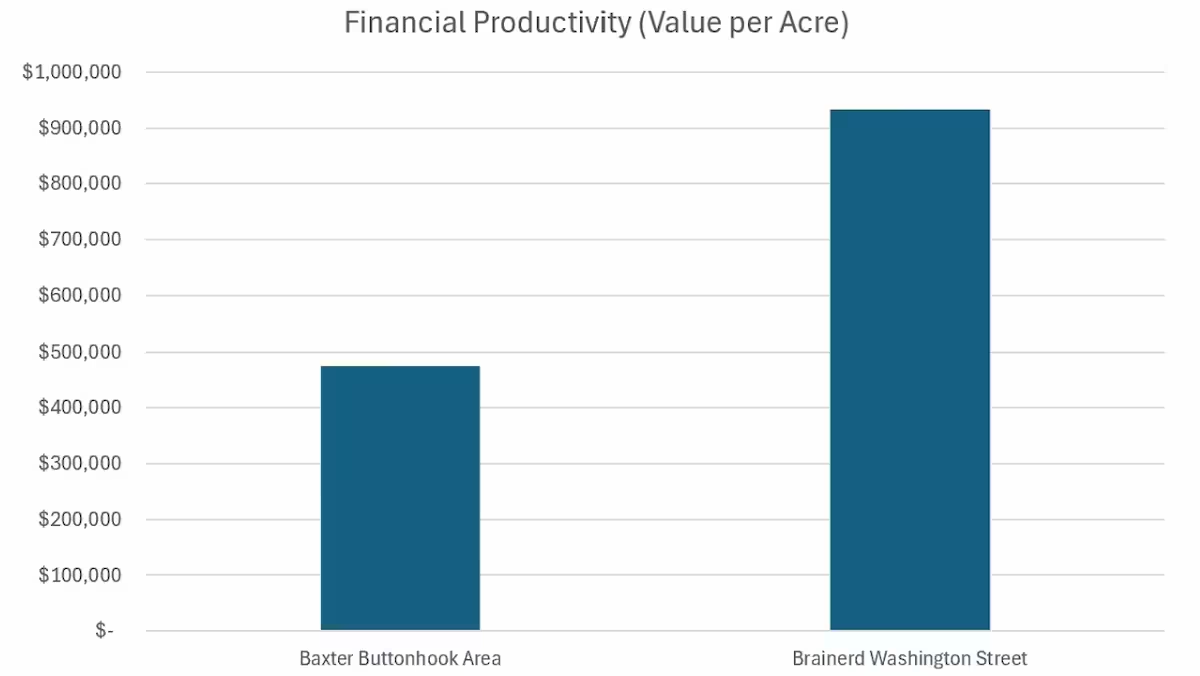

The Washington Street corridor in Brainerd covers 16.5 acres, with a total property value of $15.4 million. On the surface, it looks like Baxter has more tax base, but that’s just the lazy math of economic development, the same bigger-is-better logic that created the Baxter highway strip in the first place. It’s not what return on investment actually means.

The best way to measure return is through financial productivity: how much wealth a place produces per acre of land it consumes. By that measure, Brainerd’s Washington Street corridor — despite being in broad decline — is almost twice as productive. It generates $932,575 per acre, compared to just $475,558 per acre in Baxter. That’s a 96% greater return, on land that’s already been undermined for decades by state projects that stifle neighborhood-level investments.

Despite decades of negative-yielding state investment in Brainerd, and decades of subsidies for Baxter’s frontage roads and strip development, Brainerd’s downtown is still nearly twice as financially productive as Baxter’s strip. That’s what a real return on investment looks like.

And that’s what resilience looks like. Baxter’s strip is a shiny showpiece built on the most fragile of foundations. Brainerd’s core downtown is so financially strong that even after decades of decline, it still outperforms.

The buttonhook isn’t an investment. It’s a life preserver. The only reason these properties in Baxter have any value at all is because the state built a highway to serve them. And now, the Chamber of Commerce president insists these businesses are driving the local economy. That’s absurd. They’re being propped up by one state subsidy after another.

Meanwhile, in Brainerd, MnDOT is doing the opposite. It's stripping away parking, removing turning movements, and prioritizing through traffic at the expense of local access. The state’s investments in Brainerd actively diminish its value. And yet, even with the deck stacked against it, Brainerd’s historic district produces nearly twice the wealth per acre.

Yet, who gets the state’s economic development money? Baxter. That tells us either nobody involved with Corridors of Commerce is doing the math, or this has never really been about return on investment. If it’s the former, that’s embarrassing. But I think we all know it’s the latter.

Who Speaks for “Business”?

If this were really about supporting business, the state would be investing in Brainerd’s downtown, the place with nearly double the financial productivity, the place where small businesses are rooted in the community. But that’s not who gets championed.

Instead, we get the president of the Brainerd Lakes Chamber of Commerce standing up at city meetings and insisting the buttonhook is about “commerce.” And by commerce, he doesn’t mean Brainerd’s small businesses. He means the fragile cluster of national chains and hanger-on businesses whose value only exists because of the ongoing state subsidy of Baxter’s commercial strip.

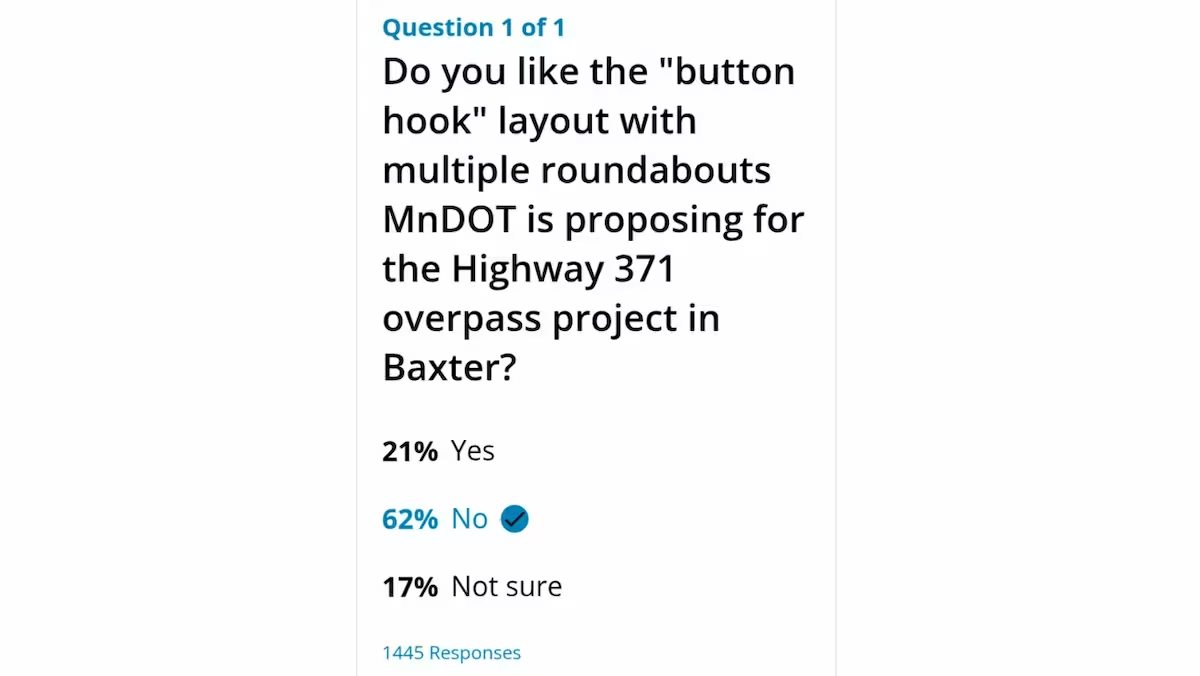

The Chamber president and I have been on the exact opposite side of every major public investment project since he arrived in Brainerd. He helped secure the buttonhook funding. He lobbied for Corridors of Commerce money. And now he’s back arguing that the design must maximize access for tourists and highway travelers, so they don’t miss a gas station or a chain restaurant as they glimpse it out their window at 60 mph.

That’s what passes for “commerce” in this vision: $58 million spent to make sure you don’t miss an opportunity to impulse stop at a corporate chain. It’s not driven by facts, math, or financial analysis. And it’s not my vision.

Meanwhile, despite the infusion of tens of millions in cash, 20% of Baxter businesses surveyed said they might close, relocate, or sell if the buttonhook goes forward, according to the Chamber itself. Half expect to lose revenue. That’s not resilience. That’s fragility. A business model that can’t survive a roundabout is not a business model worthy of public subsidy.

Yet, the Chamber insists this is what economic development looks like. A decade ago, Minnesota’s top transportation lobbyist called Baxter’s strip development the state’s “classic case” of successful public investment. That’s the same outdated logic the Corridors of Commerce program still follows: If it’s growth, it must be good. If it’s bigger, it must be better. If it’s paved, it must be progress.

But here’s the truth: These are not the kinds of investments that build community wealth, local ownership, or long-term prosperity. They are subsidies to corporations, dressed up as economic development and defended by a Chamber president whose job is to say “yes” to growth, no matter the cost.

The Real Villain

The buttonhook is not an accident. It’s the predictable outcome of a funding system that rewards the wrong things. Corridors of Commerce was written into law to funnel millions of dollars into projects that make highways wider, faster, and more accessible to freight and national chains.

Safety? Congestion? Community vitality? Those are side notes, checked boxes to dress up a subsidy program.

And here’s the thing: This isn’t unique to Corridors of Commerce. The entire system of highway funding is treated like economic development, when in reality, it has become the single greatest source of wealth destruction in our local communities.

The absurdity runs deep. In Baxter, Corridors of Commerce is spending $58 million to serve commerce on $40.8 million of property. In Brainerd, the same state is depressing values in a downtown that already outperforms Baxter in productivity nearly two to one. That’s not commerce. It’s lighting tax dollars on fire.

It doesn’t have to be this way. If Corridors of Commerce really aimed to foster economic growth, it would look very different. Slowing traffic for eight blocks in Brainerd, planting trees, improving bike and walk crossings — these are tiny investments with huge returns. A fraction of what we’re spending on the buttonhook would yield far greater economic impact in the core of Brainerd. If we understood what actually creates wealth — supports commerce — that’s what we’d do instead.

That’s why I’ve been clear about my vision. I support — and have for decades — building an interchange at 371 and 210. MnDOT’s single-point urban interchange design works if paired with closing Excelsior, Design, and the other redundant access points. That would improve traffic flow, reduce crashes, and avoid wasting tens of millions on maintaining direct access to gas stations, strip malls, and big-box stores. Those are subsidies without a return, and the taxpayers of Minnesota shouldn’t be tapped to support that.

Baxter residents — and even tourists and commuters passing through — will still be able to access the strip malls, fast food, and big-box stores along the 371 corridor. It will just take a tiny bit more time to do so. That’s a small price to pay for a massive reduction in congestion and a tremendous improvement in safety. I don’t want anyone dying so someone can get to Target, Best Buy, or Taco Bell a few seconds quicker.

I’ve been clear about my vision for Brainerd, as well. Instead of removing parking to speed traffic, MnDOT should be removing lanes. The slight cost of traffic delay through nine blocks of downtown is minimal compared to the tremendous increase in financial value that would create. And it would be far cheaper than the overengineered project they are currently pushing. If we are serious about commerce, this is clearly the winning move.

The Corridors of Commerce program doesn’t build strong towns. It builds fragile ones. It doesn’t invest in places that grow stronger over time. It props up businesses that need endless subsidies just to survive. It doesn’t expand opportunity. It entrenches decline.

Corridors of Commerce is the villain of this story. But the deeper problem is that we continue to treat highway spending as our default economic development program. That might have made some sense in the 1950s, but that time has long passed. This antiquated thinking needs to end.

We don’t need another decade of this program. We don’t need another $2 billion poured into fragile highway strips that can’t even pay their own bills. If we’re serious about commerce, let’s invest where the returns are real. It’s time to bury Corridors of Commerce, and with it the delusion that development along highway corridors is the path to prosperity.

That’s how we start to build a nation of strong towns.

.webp)