Iowa just opened the door—literally—for more housing options across the state. With the signing of Senate File 592, all cities and counties in Iowa will now be required to allow accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in areas zoned for single-family housing. It’s a quiet but powerful change that makes it easier for people to stay close to loved ones, afford their homes, and build stronger communities from the ground up.

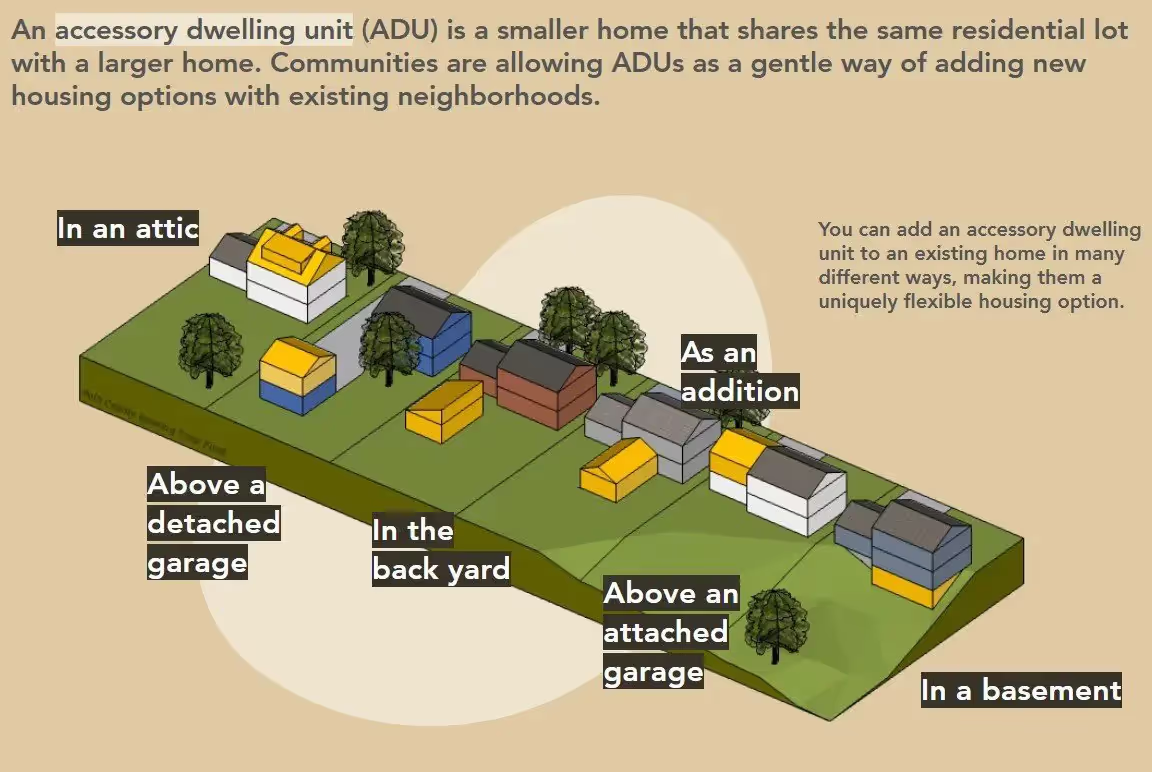

ADUs—also known as granny flats, backyard cottages, or in-law units—are modest, self-contained homes located on the same lot as a primary residence. While the concept may feel new to some, it’s really a return to a time-tested idea. Some of the earliest ADUs in the U.S. were carriage houses, built for horse-drawn buggies but often used as living quarters for household workers or extended family. These kinds of small, flexible homes were common through the early 20th century, but their popularity declined after World War II as postwar suburban growth and exclusionary zoning codes pushed communities toward uniform, single-family housing.

Now, Iowa is reversing that trend. Under the new law, homeowners statewide will be able to add ADUs by right, without navigating onerous rezoning or special-use permits—so long as the units meet basic requirements.

"People want to age in place but sometimes they don’t have a place to do it,” said Paige Yontz, state advocacy manager for AARP Iowa, which supported the legislation. “But it’s not just a solution for [the elderly]. It’s also one for caregivers. … I have had many caregivers say, ‘I can’t drive across town to take care of my mom, but if she lived in something attached to my house—’” That kind of flexibility is exactly what ADUs offer.

Yontz called them “a unique solution,” adding: “It’s not just adding an addition to your house … it’s creating separate living quarters with a bedroom, kitchen and bathroom, spaces that aren’t shared with the main house.”

The new law is especially important in a state where aging demographics and housing shortages intersect. As of 2023, 95 of Iowa’s 99 counties were experiencing population loss, and many cities were struggling to retain young families and support older residents. Meanwhile, high construction costs and tight zoning rules made it hard for new housing to keep pace.

The change could also spark more private investment. In cities like Des Moines, rules had required homeowners to live in either the main house or the ADU. But that owner-occupancy mandate is now prohibited under the new law. “I’ve heard speculation that if Des Moines didn’t have the ownership requirement, we’d see more of them being built—that an investor could get involved and use the property as a rental cash generator,” said Jason Van Essen, planning and urban design administrator for the city. “With the new state law, maybe we will.”

Of course, cost is still a challenge. The Polk County Housing Trust estimates that building an ADU can run between $50,000 and $150,000, depending on size and configuration. That’s why the next step is building support systems—especially around financing.

AARP Iowa is assembling a coalition to educate cities, counties, and lenders about ADUs. That includes sharing lending models from other states to help financial institutions understand how these small homes fit into larger housing strategies. “We want [financial groups] to understand what this would look like from the lending standpoint,” said Michael Wagler, state director for AARP Iowa.

ADUs won’t solve the housing shortage overnight, Wagler noted. Instead, they pave the way for gentle infill. A basement apartment here, a backyard cottage there. Over time, these kinds of small-scale additions help neighborhoods evolve in affordable, flexible ways—without changing their character or depending on large public subsidies.

By legalizing ADUs across the board, Iowa is saying yes to that kind of incremental, bottom-up growth. It’s a policy that puts power in the hands of homeowners, not just developers. And it reflects a broader shift: people want neighborhoods that work for multiple generations, incomes, and living arrangements—not just one.

If your town is ready to build a more resilient housing future, check out Strong Towns’ Housing-Ready City Toolkit—a practical, people-first guide to bottom-up zoning reform and policy change. Iowa’s done the hard part. Now it’s time to make those changes real on the ground.

.webp)

.webp)