In 1900, Chicago was the world’s fastest-growing city. Its population had ballooned from 300 thousand to 1.7 million residents in just 30 years, making it the fifth largest city on earth after London, New York City, Paris, and Berlin.

Chicago was the world’s urban laboratory, ground zero for the new ideas and technologies that would shape modern industrial democracies. The city was America’s railroad hub, the birthplace of the skyscraper, home to the largest electrified public transit system, and the epicenter of commerce and the labor movement. Its innovations in design, sanitation, education, industry, and civic life were the envy of its ancient peers. People from all over America and the world moved to Chicago to participate in its cultural and economic explosion, forming a diverse and upwardly mobile early middle class.

These new Chicagoans needed new housing that provided access to jobs and space for growing families. They didn’t have the luxury of wasting land, labor, or materials. Bang-for-the-buck was the mandate of the day. Luckily, the second industrial revolution gave their bucks more bang than ever.

Modern Housing for the People

The result was the Chicago 2, 3, and 4-flat—compact buildings with two to four stacked apartments that could fit on Chicago’s narrow 25 x 125-foot lots with space for a backyard. These 2-to-4-flats often replaced low-slung wooden homes and shacks without electricity or running water, incrementally “thickening up” well-located neighborhoods through the traditional development pattern.

The apartments had a front room, a living room, multiple bedrooms, and full-sized kitchens and bathrooms. 2-to-4-flats were often the first buildings in their neighborhood to have brick exteriors, back porches, indoor plumbing, electric lighting, and radiator heating from a central boiler.

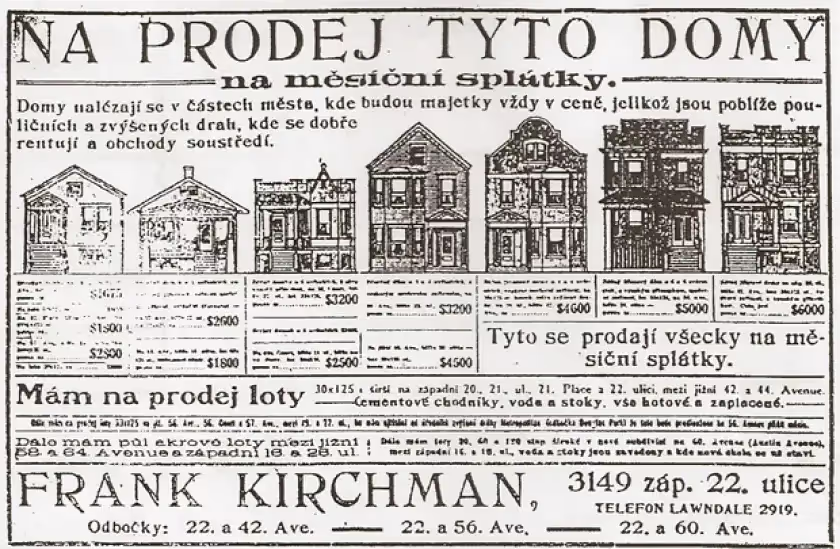

To build a 2-to-4-flat, a working family would buy a city lot with hard-earned savings and then take out a loan from a neighborhood savings & loan company using the land as collateral. The loan would pay a local architect to design the building and a local builder to construct it. In an era before multidecade mortgages when interest rates were high and loan terms were short, the family paid off this debt as quickly as possible. To limit the debt burden while thinking ahead, many 2-to-4-flats were built with an unfinished half-basement that could be converted into a garden apartment later.

The designs had flexibility built in. Elderly owner-occupants could move to the ground floor unit while housing their adult children’s families or renters upstairs. Full length apartments could be split into front and rear units for smaller households with simple changes to utilities and plumbing. Rents per square foot in 2-to-4-flats were often cheaper than larger apartment complexes

The idea caught on. Architects created reusable designs for different budgets and aesthetic preferences. Local builders cut costs by buying raw materials for multiple construction projects in bulk. 2-to-4-flats were so successful that today virtually every Chicago neighborhood has them. They account for one-fourth of Chicago’s housing stock and one-third of units with rents below $900. They are everywhere, largely affordable, and have been an integral part of their neighborhoods for over a century.

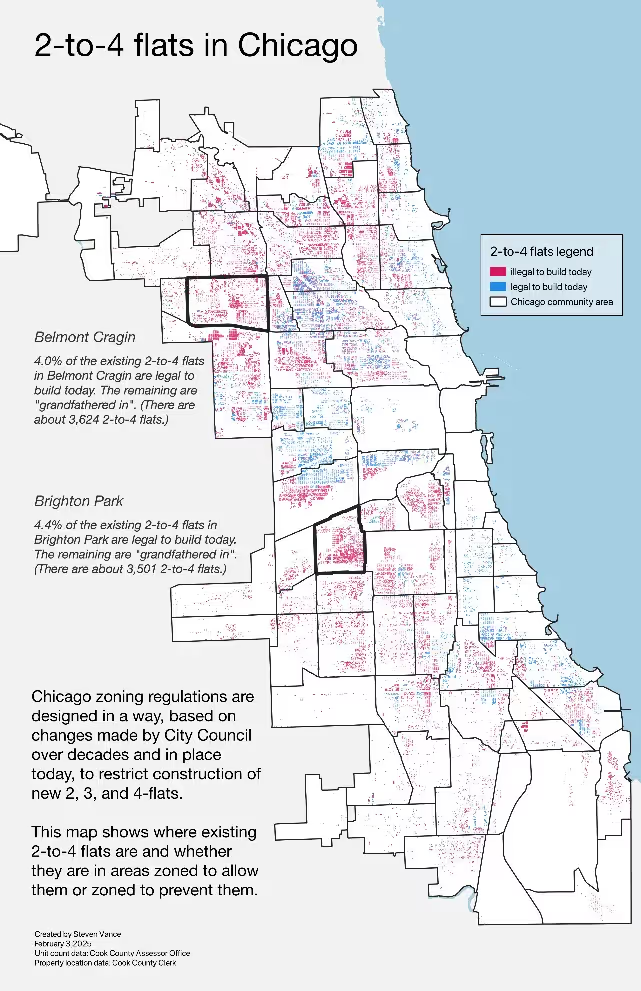

So why are 2-to-4-flats illegal to build in 80% of Chicago today?

The Great Downzonings

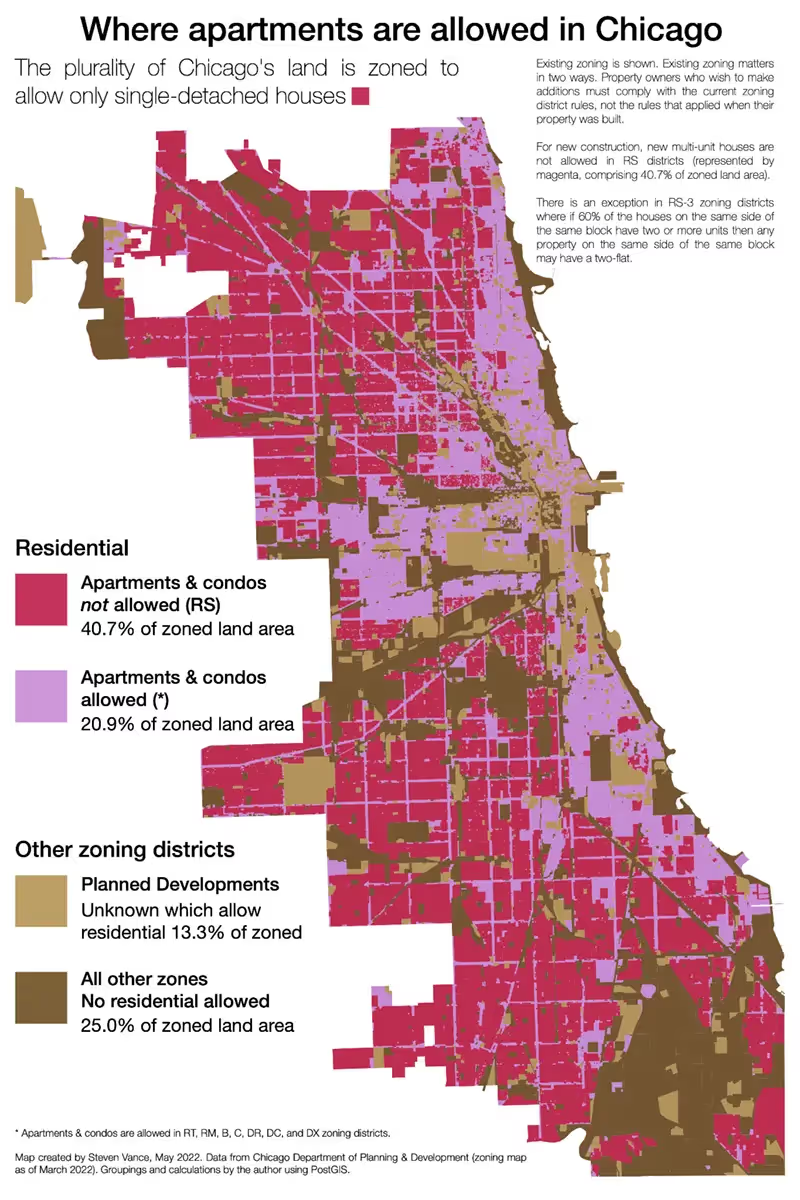

The median Chicago 2-to-4-flat is over a century old, built around 1917. Chicago introduced its first zoning code in 1923 and went through three major overhauls in 1944, 1957, and 2004. Every iteration introduced increasingly restrictive rules for unit counts, setbacks, minimum parking requirements, height limits, and floor area ratios. Between each iteration, large parts of the city were downzoned to prevent anything other than single-family homes from being built.

This was Chicago’s version of the Suburban Experiment. After WWII, subsidized highways, cheap gasoline, and government-backed loans made it profitable to build car-dependent places all at once to a finished state. Planners and politicians called traditional neighborhoods “blight” while hailing single-family subdivisions and modernist housing projects as the future. New zoning codes and lending standards prevented existing neighborhoods from evolving, motivating residents to view would-be neighbors as competitors over scarce housing and parking.

In Chicago and other North American cities, downzoning has effectively mandated suburbanization by attrition. Our urban neighborhoods are not just locked in amber—they are actively encouraged to dismantle themselves. Most surviving 2-to-4-flats today are deemed legal non-conforming based on the downzoned lots they sit on. They cannot be rebuilt or substantially renovated as anything other than a single-family home.

In richer neighborhoods, this has led to exploding property values and the de-conversion of thousands of 2-flats into single-family homes. In poorer neighborhoods—which suffered from redlining, freeway construction, and urban renewal programs—this has led to the demolition of entire city blocks. Much of the long-vacant land on Chicago’s south and west sides used to contain 2-to-4-flats. Single-family homes and large planned-development apartment complexes don't make financial sense at current land values or construction costs.

City Neighborhoods as Strong Towns

Visitors to Chicago who venture outside of downtown are surprised to find neighborhoods that feel more like a pre-suburban American town than Manhattan. Thousands of towns and cities in North America also came of age around 1900, and they adopted many of the same housing types and techniques before zoning. In Chicago, these walkable communities are next to each other, connected by a comprehensive train and bus network that links them to a wealth of jobs, education, and world-class amenities.

Chicago’s current zoning map treats 2-to-4-flats as a historical mistake to contain and phase out in favor of single-family homes, even as the city faces a billion-dollar budget shortfall and eroding tax base while doubling down on highly subsidized megaprojects that take decades to break ground. Despite this handicap, existing 2-to-4-flats hang on and continue to make up the bulk of Chicago’s unsubsidized affordable housing.

It’s time to re-legalize 2-to-4-flats citywide and bring back the kind of fiscally responsible incremental development that made Chicago a strong town.

.webp)

.webp)